Four

days after Roliša Junot, with 13,000 men and 24 guns, marched north from

Lisbon to attack the British at Vimiera, a few miles south of Roliša.

Wellesley himself had been reinforced by a further 4,000 men, belonging to

the brigades of Anstruther and Acland, who had come ashore at the river of

the Maceira river, about fifteen miles south of Roliša. These troops,

which brought the number of men under Wellesley's command to 17,000, were

welcome reinforcements. Not so welcome, however, was the 53 year-old Sir

Harry Burrard who had arrived off the mouth of the Maceira on August 20th.

Burrard

had arrived in Portugal to assume command of the army although this came

as no great surprise to Wellesley who had been forewarned of his coming by

Castlereagh. It was entirely a political move from which Wellesley could

take little comfort. Furthermore, two more British officers, Sir Hew

Dalrymple and Sir John Moore, both of whom were senior to him, were also

on their way to Portugal. Nevertheless, Wellesley joined Burrard aboard

his ship and having appraised him of the situation Burrard decided that it

would be unwise to take any further offensive action before the arrival of

Moore's reinforcements which were known to be due shortly. Having been

informed of this Wellesley returned to his troops, determined to do his

best as long as he remained in command, while Burrard remained on his ship

for the night.

When

Wellesley retired for the night he did so having placed six of his

infantry brigades with eight guns on the western ridge lying on the south

of and running parallel to the Maceira river while a single battalion was

placed on the eastern ridge as guard. The river itself flowed south

through a defile between the two ridges and continued on to the rear of

the village of Vimiera which itself was situated on a flat-topped, round

hill. Here, Wellesley had placed his other two infantry brigades as well

as six guns. The village was separated from the two ridges not only by the

Maceira but also by a tributary, which flowed along the southern foot of

the eastern ridge.

The

hush of night had hardly descended upon the British camp when reports came

in that the French were advancing in force from the south. In fact, the

French under Junot numbered around 13,000 men, still 4,000 fewer than

Wellesley but having five more guns. Once again Delaborde's division was

present along with 6,000 men under Loison.

Long

before dawn showed itself on the morning of August 21st Wellesley was up

on the western ridge, peering through his telescope, but as yet no French

troops were to be seen so the British troops wiled away the early morning

cooking their breakfasts. At about 9 o'clock, however, clouds of rising

dust were spotted away to the east and soon the glint of bayonets, shako

plates and other accoutrements could be seen as they sparkled in the

shimmering sunlight.

From

the direction of Junot's approach it was obvious that Wellesley's left

flank was being threatened which prompted a hasty redeployment of his

forces, mainly involving the transfer of three of his brigades from the

western ridge to the eastern ridge, leaving Hill's brigade and two guns

alone on the western ridge. Wellesley himself also moved to the eastern

ridge from where he controlled the battle.

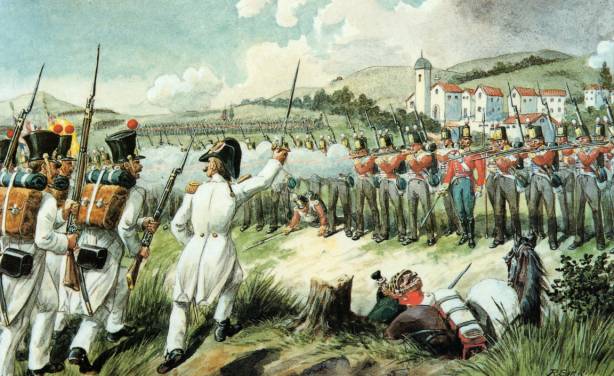

The 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment standing firm against a French

attack at Vimiera - by R. Simkin

The village of Vimiera itself was held by the brigades of Fane and Anstruther and it was against this position that the main French thrust appeared to be heading. The British troops here consisted of four companies of the 2/95th and the 5/60th, all deployed in a heavy skirmishing line in front of Vimiera Hill, while on the crest itself were the 1/50th, the 2/97th and the 2/52nd. Behind them, on the reverse slope of the hill were the 2/9th and the 2/43rd, both in support. These troops were supported by twelve guns. Heading towards these 900 British infantrymen were some 2,400 French troops under General Thomieres who were formed into two columns supported by cavalry and artillery and screened by a shield of tirailleurs. The ensuing clash between the two sides marked a significant point in the Napoleonic Wars and set the pattern for a whole series of actions fought in the Peninsula between the British and French armies.

As

the dusty French columns advanced against the British infantry on Vimiera Hill they did so in the traditional, and up until this point the all too

successful, style that had swept Napoleon's armies to victory after

victory. Cavalry cantered along on the flanks, field artillery bounded

along over the broken ground, while in front of the columns hundreds of

tirailleurs engaged the British skirmish line as a prelude to the assault

on the main British line. The formula had been tried and tested and it had

proved successful. And yet here, on the slopes of the hill in front of Vimiera, Wellesley's skirmishers had turned the tables for so effective

was his light infantry screen that the men of the 5/60th and the 95th were

only forced back following the intervention of the main French columns.

The columns themselves were suffering at the hands of the British

artillery, which dealt out death in a new form, shrapnel, which swept the

French troops with dozens of musket balls from their exploding cases. But

it was the clash between the British line and the French column that was

to become the standard form of conflict and perhaps the most enduring

image of the war in the Peninsula.

At

Vimiera, this scenario was premiered with devastating results. The French

columns, 30 ranks deep by 40 wide, advanced noisily and confidently

against the 900 British troops, formed in a silent, two-deep line. As the

French approached to within 100 yards the British troops, in this case the

1/50th, levelled their muskets and delivered a crashing volley into the

tightly packed ranks of Frenchmen. As the column came on, so the effects

of each of the succeeding volleys, fired at fifteen-second intervals,

increased. The French ranks thinned at each discharge while they

themselves were able to bring only 200 of their own muskets - those in

front and on the flanks - to bear on the British. It was a somewhat simple

mathematical equation that the French commanders were never quite to

comprehend during the war and when they did try to deploy their men into

line the effects of concentrated British musketry made it almost

impossible. Thomieres did his best to get his men into line but it was

hopeless. The columns melted away to the rear with Fane's riflemen close

on their heels.

To

the south of this first column, Thomieres' second column was making

progress towards the British line. The column, also some 1,200-strong,

suffered less from artillery fire owing to the nature of the terrain over

which it passed but when it neared the British line it began to suffer the

same fate as the column on its right. Anstruther's brigade duly dealt the

decisive blows, the precise, controlled volleys of the 2/97th rolling from

one end of its line to the other, ripping great gaps in the French column,

and when the 2/52nd and 2/9th closed in on each side of them the French

resolve disappeared and once again Fane's riflemen enjoyed a brief chase

after them before being called back. In their panic, the French abandoned

all seven of the guns they had brought forward with them, the horses and

gunners falling victims earlier to the accurate fire of the Baker rifles.

With

the initial French attacks having been repulsed Sir Harry Burrard picked

his moment to appear on the battlefield. There appeared little danger to

the British at this time, however, and Sir Harry allowed Wellesley to

finish the battle himself.

No

sooner had Burrard satisfied himself as to the progress of the battle than

the French committed two more columns to the attack. Once again the

village of Vimiera was the centre of the attack, carried out by two

columns, each of two battalions of grenadiers. The British line steadied

itself once more and braced itself for yet another attack. Colonel Robe's

gunners worked furiously at their guns as they poured shot and shell into

the leading French column. Enemy artillery attempted to reply but their

fire was ineffective and there was a real danger of firing into their own

men who were skirmishing with Fane's riflemen. In spite of the fire being

poured into the column it pushed on, moving across the ground lying

between the routes of the last two French attacks. Gradually, the

enveloping fire from 2,000 British muskets of the 2/9th, the 1/50th and

the 2/97nd brought the column shuddering to a halt and as Wellesley's men

advanced down the hill the French column finally gave way and scattered,

abandoning four guns that had been brought forward with it.

While

this last attack had been in progress the second column of grenadiers had

managed to move round the left flank of the 1/50th and soon had a clear

run into the village of Vimiera itself. The French incurred heavy losses

as they swept into the village through a hail of lead and cannon shot.

Here, in the narrow, jumbled maze of houses - a sort of prequel to the

fighting at Fuentes de O˝oro - the French came face to face with the

2/43rd which Anstruther had thrown forward. The ensuing fighting was

chaotic and confused and bayonets were bent and bloodied. The British

troops, in spite of their inferior numbers, managed to thrust the French

from the village and the British line was restored.

Wellesley

had just 240 British cavalry available to him, all from the 20th Light

Dragoons under Colonel Taylor, but with all of the French attacks until

now having been repulsed he chose the moment to launch them in a

counter-attack. Taylor's men, having dispersed a French infantry square,

quickly became intoxicated with their success and rode on at speed,

outdistancing their own supporting guns and doing little damage to the

French. Almost half the light dragoons were either killed, wounded or

taken prisoner - including Taylor himself who was mortally wounded - when

they collided with fresh, and more numerous French cavalry. The charge was

just the first in a sad series of misadventures of the British cavalry in

the Peninsula, punctuated by rare but glorious triumphs.

On

the eastern ridge above Ventosa, which lay at the eastern end of the

ridge, the French were again attacking in strength with 3,000 French

infantry under General Solignac who was supported by a small number of

cavalry and three guns and a further 3,200 infantry, supported by

dragoons, under General Brennier. These first of these two forces advanced

on Ventosa itself while the second force passed to the north with the

intention of attacking the ridge from the north-east.

The

results of both of these attacks were predictably similar to the earlier

French attacks elsewhere on the battlefield as both Solignac and Brennier

advanced in column against their British adversaries who waited for them

in line. The first force, consisting of three columns, struck that part of

the line held by Ferguson's brigade. The French were met by a devastating

series of volleys, fired by platoons, which blasted away the heads of the

columns and prevented Solignac, desperately trying to deploy his own men

into line, from making any progress at all. After a few minutes the French

were in full retreat, once more abandoning their guns.

No

sooner had Solignac's attack come to grief than Brennier's columns fell

upon the rear and flank of three of Ferguson's battalions, the 1/71st,

1/82nd and 1/29th. By the time the first two of these battalions adjusted

their positions to meet them Brennier's men closed on them and in a

confused fight both the 71st and 82nd were pushed back, the French

retaking the guns which had been abandoned by Solignac. However, the

1/29th had sufficient time to alter its position and was soon setting

about the right flank of the attacking French columns who were forced to

halt in the face of the 29th's musketry. Ferguson's other two battalions

reformed and together the three British units forced Brennier's men back.

The French appeared to have little stomach for the fight and were soon

fleeing in a disorderly fashion, leaving behind them their commander,

Brennier, who was wounded and taken prisoner. The three guns, retaken

briefly by the French were once again in Wellesley's hands along with a

further three guns which had accompanied Brennier.

It

was barely noon, and every single French infantry battalion present at Vimiera

had been thrown into the attack, only to be seen off by the

devastating effects of British musketry. 720 British troops had been

either killed or wounded whereas the French had suffered three times that

number including 450 killed. Now was the time to advance and pursue the

defeated French who had been all but routed that morning. The road to

Lisbon now lay open, a fact that should have spelt the end for Junot and

his army but Sir Harry Burrard decided that any further action was

unnecessary and the glorious opportunity went begging despite the

impassioned pleas of a very frustrated and angry Sir Arthur Wellesley.

Junot's force, therefore, was allowed to retreat to Lisbon without any

hindrance.

Burrard

himself did not enjoy the position of commander-in-chief for too long for

the very next day an even older general, Sir Hew Dalrymple, in turn

superseded him. Dalrymple also decided that any further action was

unnecessary and together the two elderly generals, devoid of any real

military experience and totally failing to grasp the advantageous military

situation facing them, agreed to the notorious Convention of Cintra,

whereby it was agreed that Junot and his army, along with their arms and

accumulated plunder, would be given free passage back to France

unmolested. Following this, Burrard, Dalrymple and Wellesley were recalled

to England to explain before a Court of Enquiry how they had allowed the

French army to escape. Wellesley himself had not even been privy to the

treaty but signed it nevertheless when ordered to do so by Dalrymple.

With

all three men having returned to England command of the 30,000 British

troops in Portugal devolved upon the 47 year-old Sir John Moore who was

about to lead the army through one of the most tragic episodes in the

Peninsular War, an episode which was ultimately to cost him his life.