During the final phase of the First World Was, late in September 1918 the British Fourth Army and the French First Army went for an attack on the Hindenburg Line in the region of St. Quentin Canal.

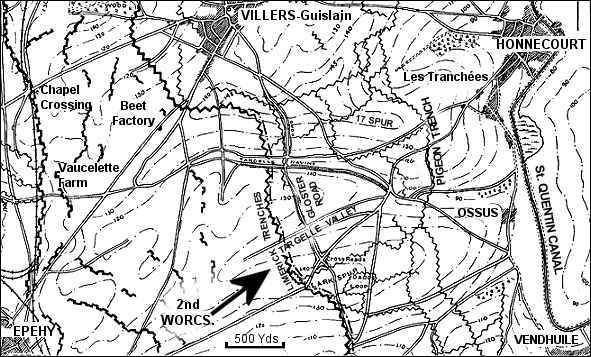

But that attack had to be assisted by simultaneous attacks further north, lest the enemy’s artillery on the La Terrière plateau should concentrate their fire on the decisive front. So the 12th and 18th Divisions were to attack Vendhuille, while further north the IVth and Vth Corps of the Third Army made a subsidiary attack from Epehy to Marcoing. On the right of that latter attack the 33rd Division was to advance from the height of Epehy to gain the German forward positions west of the Canal. On the left flank of the 33rd Division the 98th Brigade were to storm Villers Guislain: on the Division’s right flank the 100th Brigade, including the 2nd Worcestershire, were to attack down the Targelle valley towards Ossus.

That attack, as we have said, was subsidiary to the main operation, and could not be expected by itself to achieve any great success: consequently, since there were not enough tanks and artillery to assist adequately the whole front of attack, all the tanks and most of the available guns had to be concentrated behind the main attack further south, leaving only inadequate support on the front of the 33rd Division. The attack of the 33rd Division was supported only by the 33rd Divisional Field Artillery—two Field Brigades without any addition of heavier pieces. In contrast, the decisive attack on the right was supported by 44 Field Brigades and 21 Brigades of medium or heavy artillery, and was assisted by a strong force of tanks.

Also the subsidiary attack was to be started earlier than the main attack in order to deceive the enemy and to engage the fire of the German guns. That latter provision entailed an especial disadvantage for the 2nd Worcestershire; for the Battalion formed the extreme right flank of the subsidiary attack, and consequently the Worcestershire companies would have to advance with their right exposed to enfilade fire from Lark Spur until the subsequent movement of the 12th Division further to the right.

Through the night of the 28th September 1918, the support companies of the 2nd Worcestershire filed forward to the front, and before dawn the Battalion was deployed for attack. In the front line,” Limerick Trench,” from right to left were “D” and “C” Companies; in the second line behind them were “A” and “B” Companies. The two leading companies were to capture the sunken “Gloster Road”; then the two supporting companies would pass through and take “Pigeon Trench “beyond.

2nd Battalion Worcestershire attack on

the 29th September 1918

At 5.30 a.m. on the 29th September 1918, the guns behind the 33rd Division opened fire and the battle began, the main attack on the right started twenty minutes later. Scrambling out of their trenches the Worcestershire platoons (the two leading companies advanced in deep formation; two platoons in front line, one in support one in reserve. The front line platoons were in extended order) advanced as rapidly as possible through a storm of German shells; but the rain of the previous days had converted the shattered ground into deep mud, and the laden troops could not keep up with the barrage. The British shrapnel burst for a few minutes along the line of the sunken “Gloster Road “ and then moved on down the valley. As soon as the shells ceased to burst over the road the German machine-guns came into action one after another, in all, 7 machine-guns appear to have opened fire from the sunken road and from the Cross-Roads. From the cutting in front and from the Cross-Roads to the right came the hard stammer of their firing, and under the hail of their bullets the attack withered away. Through the smoke of the shell-bursts the platoons in rear saw their comrades in front collapse, but they pushed on in their turn only to meet a like fate. All the platoons of the two leading companies had been shot down and the majority of the two support companies had fallen before the survivors came to a halt half-way to the road and took cover as best they could.

It was not possible to send a message back across that open ground swept by machine-gun fire, and it was not until after 10.0 a.m. that it could definitely be reported that the attack had failed. About that time a merciful mist drifted down and veiled the battlefield. Under cover of that mist the survivors of the attack regained Limerick Trench. German shells were still raining down all around, and a tremendous thunder of gunfire on the right flank told them that the main attack had been opened along the whole front of the Fourth Army.

Throughout the rest of that day shells and bullets struck around the trenches, which the survivors of the Battalion were holding. Orders for a further attack were followed by counter-orders; and the position was unchanged when darkness fell. That night came cheering news. The great attack on the right had been successful. The Bellicourt defences had been stormed, the St. Quentin Canal had been crossed, and the Hindenburg Line was broken.

The fall of the main defences further south entailed the retreat of the enemy in front. Patrols were sent forward before the dawn. They found the sunken road empty save for a few dead. Cautiously they made their way down the valley, reconnoitred “Pigeon Trench” and found it deserted, then pushed on to the bank of the canal beyond. Machine-guns spat at them from the eastern bank; but Ossus and all the ground west of the canal had been evacuated.

On the left and closest to the road lay Lieutenant R. K. Wright’s platoon of “C“ Company. In front lay the subaltern, a bomb grasped tightly in his hand: behind him lay his men, all struck down in the moment of charging. “His leading,” recorded the Battalion War Diary, “must have been magnificent.”

To the right and but little further from the enemy position were found 2/Lieutenant G. Lambert’s platoon. They too had all been killed; and they lay, riddled with bullets but still in line facing forward, their dead subaltern a few yards in front.

Further to the right the two leading platoons of “D” Company had closed towards the Cross-Roads, and they lay strewn in a semi-circle as the machine-guns had caught them. “Their position” says the War Diary, “bore witness to the splendid effort they had made to reach their objectives.”

Of the four platoons which had led the attack every officer and man had been killed by the storm of bullets at close range. The ground behind was littered with the dead and wounded of the other platoons who had followed them.

Lieut.-Colonel G. J. L.

Stoney

Commanding 2nd Battalion Worcesters

That sacrifice of brave men must at first have seemed useless to the survivors of the Battalion—who indeed wrote bitterly of the weakness and ineffectiveness of the supporting artillery fire; but the sacrifice had not been useless. The attack had diverted much of the enemy’s artillery, and had drawn to the defences in front a fresh German Division, the 30th Division, from the enemy’s reserves (the enemy who actually met the attack were Jäger Battalions of the Alpine Corps, a formation which bad gained a high reputation). Thus weakened, the enemy’s line further south had given way before the attack of the Fourth Army; and the strongest bulwark of Germany was broken. The officers and men of the 2nd Worcestershire who lay dead in the valley of the Targelle were part of the price, an inevitable part of the price of the decisive victory of the War, the greatest battle ever won by British arms.

By midday of 30th September 1918, the advancing troops of the 33rd Division had reached the line of the St. Quentin Canal along the whole Divisional front and had begun to consolidate the ground gained. Under intermittent shell-fire the 2nd Worcestershire, now mustering only some 200 bayonets, established outposts and reconnoitred the enemy’s deserted trenches (A German trench-howitzer found abandoned in “Pigeon Trench’s on the morning of 30th September 1918, is now at the Depot of the Regiment). Patrols explored the river bank, searching for possible crossing places. Throughout the day good news came in ; the enemy’s front further south was shattered; further north the Divisions of the First Army were fighting, as we have seen, on the very outskirts of Cambrai.

By dawn of 1st October 1918 the position along the canal bank was fairly secure. Parties were then sent back to bury the dead; who were laid to rest in the ground over which they had fought, the eight subalterns of the leading platoons being buried together at the Cross-Roads which the attack had tried to gain.

After dark patrols were sent forward, who ranged up and down the banks of the canal seeking a practicable crossing. But from the far bank the enemy sent up flares and the German machine-guns fired repeatedly. No crossing could as yet be effected; and during the next two days the position on the front of the 100th Brigade remained unchanged. Then the 19th Brigade took over the line along the canal, and the 1st Queens and 1st Cameronians relieved the platoons of the 2nd Worcestershire. The platoons of the 2nd Worcestershire filed back along the communication trenches up the Targelle Valley and over the ridge by Vaucelette Farm to a bivouac camp on the reverse slope behind Epehy. There the Battalion rested and reorganised during the next four days. On October 6th, the” Battle Reserve “of the Battalion rejoined to replace, in some measure, the casualties. That reinforcement included five officers :—Capt. C. C. Tough, M.C., Lts. Croydon-Fowler, Williams, Laughton and Dudley.

The great attack of 29th September 1918 had achieved its principal object; the enemy’s strongest defences, the main Hindenburg Line along the St. Quentin Canal, had been broken. If those elaborate defences could not withstand the attack of the Allied Armies it was clear that no less formidable line could maintain a long resistance. But though the main Hindenburg Line had been broken, the Reserve Line of defence, the “Beaurevoir Line,” some two to three miles in rear of the Canal, still barred the path of the British forces. To break that last line of resistance a fresh attack was planned and fresh forces were brought forward. Among those fresh forces was the reconstituted 25th Division.

The 25th Division had moved on the 29th September 1918 from billets west of Albert to hutment camps near Montauban in the old Somme battle-ground. On October 1st, when the success of the great attack was assured, the Division was ordered to move still closer up, to Combles. Then came orders for the Division to move right forward to the front line near Le Catelet.

Thus it came about that the 1/8th Worcestershire moved forward once more over the ground they had known so well in the Spring of 1917. On September 29th the Battalion was carried forward from Warloy by bus across the devastated trench line to camp in Nissen huts near Montauban. On October 1st, “a heavenly summers day,” the 1/8th Worcestershire marched forward, with drums beating, to Combles; there the 75th Brigade were quartered in huts. Next day the Brigade marched onwards from Combles over the ridge at Bouchavesnes, the 1st Battalion’s old battlefield, down into Moislains in the valley beneath, and thence on to Nurlu. “All the time we could hear the “trampling roar of the great battle around Cambrai, and at night the sky was crimson with the “burning of the town. The next night when we reached Ste. Emilie, which we had helped to take “eighteen months before, the fire was out and we thought the town taken.” At Ste. Emilie, to which the 75th Brigade marched on the evening of October 3rd, leaving their blankets and packs behind “dumped” at Moislains, the Worcestershire battalion was indeed on well-known ground. The next day (October 4th) brought even prouder memories, for that afternoon the 1/8th Worcestershire marched forward through Templeux-le-Guerard, past that very Mound whose capture in April 1917 had been one of the finest feats of the Battalion’s history. Through Hargicourt and up the slope the column marched to a reserve position in captured trenches by Quennemont Farm, which in 1917 had been the limit of the advance. There the 75th Brigade was close behind the battlefront. German and American dead were strewn over the broken ground; and occasional shells struck along the crest-line during the night.