The 29th in the Sikh Wars - Colonel George Congreve, C.B. Letters

Colonel George Congreve was first commissioned to the 29th Regiment in 1825, was promoted Lieutenant in 1826, Captain in 1828, and Major in 1841. At the outbreak of the First Sikh War in December, 1845, he was Second-in-Command of the Battalion. Below are letters written by George Congreve to his father and brother which paint a very interesting picture of the most desperate campaigns ever fought in India. the spelling are as used at the time. Also included are other letters from other officers which relate to the events.

First Letter

MY DEAR FATHER, |

Colonel George Congreve. C.B. |

The 29th led, supported on each flank by six Horse Artillery guns. We had not advanced many yards when a battery of 12 and 18 pounders opened upon us; our guns then immediately replied to them, and the action had begun. Our advance was magnificent, nothing could exceed the steadiness of the men in spite of the cannonading we were suffering from, and our artillery behaved nobly. When about 100 yards from the enemy's guns I ordered the Regiment to fire, and from that moment I could see but little of what was going on; on, however, we went, "Forward" was the word, and forward we went under probably the very heaviest fire of round, grape cannister and musketry ever witnessed. Down went our poor fellows in sections and still never flinched, no hail storm ever fell so thick and heavy as the Sikh's shot, among us. At last we charged the guns and then such slaughter was never before seen in India; the enemy to a man stood to their guns and died by the side of them, no quarter was asked or given by either party. At this point I was shot down by a grape shot through the ankle; which compelled me to go to the rear, and I saw nothing more of the action, which with few intermissions continued until 2 o'clock p.m. on the 22nd, very nearly 24 hours. Our loss in European officers and troops has been enormous. The 29th have 67 killed and 175 wounded, almost all severely, besides 3 officers, Lucas, Molle, and Simmons shot dead, and Colonel Taylor and myself severely wounded. We took from the enemy 92 guns and a large quantity of ammunition supplies and baggage, the action having been fought within 9 miles of this place all the wounded have been brought here. I am lying in a small room attached to the building where the 29th are and have the constant attendance of Taylor our surgeon, who is very clever—my wound is doing very well and there is no fear of losing the leg, but it will lay me up for a long time. I of course suffer very great agony from it but that must be expected, it is with extreme pain and difficulty that I am able to write, but I know your anxiety would be great should you not hear from me in some way or other, the sacrifice I make is therefore nothing. This action will probably make me a Lieut.-Colonel and C.B. which is all worth having. Nothing appears to be known for certain whether we advance into the Punjaub this year or not, a few days will decide the point. In my opinion our European Regiments are too much crippled in these two actions to be in a fit state to take the field again until our recruits from England arrive. Tell William that his old Regiment the 3rd (The 3rd Light Dragoons [now Hussars]) behaved most gallantly, their charges were splendid, but I grieve to say that they have been cut to atoms, I don't think that they can now muster 100 men on parade out of about 600—little Balders commanded them and had a narrow escape, a round shot having grazed his chest. I forgot to mention my escapes which were five in number, a grape shot struck me on the peak of my cap and glanced upwards knocking me off my horse, a ball carried away part of the sleeve of my jacket without touching the skin, and another passed through the back part of the collar of my jacket, and another grazed my left leg drawing a little blood but it is nothing more than a scratch, so that my escapes are most providential. I shall be better able to write by the next mail and until then believe me, my dear father.

Your affectionate son,

(Enclosure)

NEWSPAPER CUTTING.

THE BATTLE OF FEROZESHAH (from an officer in the Bombay Artillery)

On the morning of the 21st December the Army of the Sutlej, under the command of Sir Hugh Gough and the Governor General, left the village of Moodkee, where the fight took place on the 18th, and rapidly advanced over the field of battle on the small Sikh hamlet Sultan-Khanwhallah, near which place the scouts had brought word that the enemy had intrenched themselves. On arriving here the troops were halted; this was about 10 o'clock; in half an hour we were moved forward, and the skirmishers were thrown out ahead. We then turned to the right and formed in battle array. In the meantime the Ferozepore Force, under General Littler, had gone outside of us and taken up position. We began to exchange shots with the Sikh batteries at 1000 yards; and were advanced nearer and nearer, till we came within 250 yards. By this time we heard a sharp fire of musketry on our left; this was the Ferozepore Infantry, who had rushed on and were attacking the right of the Sikh intrenchments. We then ceased firing. The infantry who were in our rear, dashed through the intervals between our guns, and went straight towards the trenches. The 29th (Queens)[see note 1 below] was the Regiment that passed through my battery. I never saw finer fellows in my life—each with a smile on his face. I took off my cap and our men gave them a cheer as they left us. All was then one mass of smoke and dust; but "Ala, they're giving it them now," as one of my Sergeants said, and the sound came r-r-r-r-r-r, the long roll of musketry, just as if they were firing a feu-de-joie on parade. The shot and shell that had just now driven through our ranks, smashing guns, men, and horses, came slower and slower; we heard a shout as the gallant fellows got to the trenches. The musketry had in a manner ceased, when a bright flame shot through the smoke, and the ground shook beneath our feet. It was a mine. Again the guns commenced; our infantry had taken one battery, but there was another behind; the men stood by the guns with heaps of muskets beside them; when one was discharged they took up another; mines exploded every minute, and but for a "hurrah" that came through the darkness—for the sun had set ere we knew it in the dust and smoke—we had had doubts of how the day was going. It was then (as the artillery was standing doing nothing, for we could not fire except on our own people) that the guns commenced and took us in flank; we were just limbered up, when a shell struck a horse-artillery wagon by which I was standing; the explosion was awful; two men were killed, one of the wheelers and the man who was riding the leaders; my Captain and I were supposed for a whole day to have been killed by it, but we escaped unhurt; the whole thing was a mass of fire; the horses, mad with pain and fright, started at full speed across the plain towards Sultan-Khanwallah; providentially no other wagons were in its way, and it was at last lost in the jungle, where it was found the next day. A sudden panic seemed to seize the whole of the native drivers (our horses are all ridden by natives), the cavalry, and three or four regiments of native infantry, who were with us, and they all started across the plain towards Sultan-Khanwallah. After a short time, however, we (the officers) managed to get them into some sort of order, and it was resolved that the artillery should pass the night at this place. The guns were still playing, and the musketry was still rolling at the Tenches, as we threw ourselves by the fires which the soldiers made from the roofs of the houses in the village. Men from the field came in every minute carrying their wounded comrades. It was about half-past eight when the musketry ceased, but the guns were blazing all night. But what were they doing all this time at the trenches? The Sepoys, from what we saw of them, were not disposed to do anything. The European Regiments had beaten the Sikhs from every gun they had in battery, plundered their camp, and driven them beyond Ferooshahah. The Sikhs had a few guns with them, which were those that troubled us that night as we lay round the fires at the village of Sultan-Khanwhallah. Some men who had been in the camp joined us, with their pockets full of rupees and gold mohurs, which they offered for a drop of water; but that could not be procured. With the night came cold, and with the cold, hunger and scorching thirst to the wounded, who were lying on every side. Thus we passed the night. When morning came no man knew his fellow—smoke, dust, hunger, and cold had so changed our faces. Again the firing commenced on our left; it was a reinforcement of 30,000 of the Sikhs, who had come up with an overwhelming force of artillery. Again we formed line and advanced on the field of action. After waiting for a couple of hours in the rear of the late intrenchments, which were then in our possession (during which time only the infantry and the cavalry were engaged), we moved on round their camp by Ferooshahah, and no sooner had we turned the corner than we were hailed with such a shower of shot and shell, that for a moment we were actually paralized. No time was to be lost, however, and we went forward at a gallop; and (when we got near enough) "Left about, unlimber for action, front, load, tire"; but it was useless, they were about 600 yards off and had our range to a T. We had about 36 guns, they about 80, out of which 56 were found out afterwards to have been heavier metal than any of ours; and they loaded as quickly as we did. I cannot express what it was better than when I say it was a "regular smash"; out of six guns two were rendered useless in less than a minute. But the destruction that was going on around me could not prevent my admiring the conduct of one or two men, who were certainly the pictures of coolness and self-possession ........................................................................ ...............................................We retreated behind their intrenchments again ; and now occurred one of the most extraordinary things, but at the same time providential, that I supposed ever occurred in the annals of History. We (i.e. the artillery and cavalry) received orders to go into Ferozepore; we considered that for the present we were overcome, but were not surprised as we had had nothing to eat or drink for two days We retreated to Ferozepore. The Governor General and Com¬mander-in-Chief had neither of them given an order to the effect that we were to retreat, and they were left with the infantry in the village of Ferooshahah. Had the Sikh artillery gone on playing on the infantry and the village, not a man could have survived, as they had cavalry to cut them up had our troops attempted to leave the place; but, no ; on a sudden the Sikh artillerymen desert their guns, and the whole army rush madly towards the river. Directly our infantry saw this, of course they rushed forward, spiked all the guns, and fired a few volleys at their retreating columns; but as they had no cavalry with them (it having gone to Ferozepore) they could do nothing more. The Sikhs thought we (the artillery and cavalry) were only going round to take them in the rear, and ran away through this mistake; whatever you may hear this is the truth. I may say, I think with reason, that in this campaign the fate of India has once or twice hung upon a hair, and a very fine hair too.

We are now on the bank of the Sutlej, but whether we shall cross, or what we shall do, no one can surmise. Provisions are becoming very scarce; we cannot stay much longer here on that account. We have contradictory reports every day about the Sikhs, but they are not worth mentioning.

Note 1: Regiments of the British Army in India were then styled "Queen's Regiments," as opposed to the separate Army of the Honorable East India Company, which afterwards was converted into the present Indian Army.

SECOND LETTER

FEROZEPORE, FEB. 14TH, 1846.

MY DEAR FATHER,

I trust this will be the last epistle written on the bed of sickness that you will receive from me, for I am delighted to tell you that in 8 or 10 days there is every hope and chance of my wounds being perfectly healed up. I shall be lame in the right leg probably for many months, but there is no doubt of its ultimately being as well as ever. I am unable as yet to put it on the ground, but a few days will work wonders. Our Army has again been fiercely engaged with the Sikhs in two hard fought general actions. They had the temerity and audacity to recross the Sutledge and endeavour to cut off some of our stores and munitions of war; about 24,000 of them, with some sixty guns, fell in with Sir Harry Smith's Division consisting of about 10,000 men and thirty guns; a general engagement ensued (The battle of Aliwal) which terminated in the total rout of the Sikh Army, leaving behind them all their guns, camp, ammunition and stores. They were driven headlong into the Sutledge, and it is reported that their loss exceeded seven thousand men, while ours did not amount to more than 500 of all arms killed and wounded; this glorious achievement was accomplished on the 28th January. Upon Sir Harry Smith's Division rejoining the Commander-in-Chief's camp on the 7th of this month, he, the Commander-in-Chief, determined upon attacking an exceedingly strong entrenched position that the enemy had erected upon this side of the river, and within three miles of our advanced picquets, and he accordingly moved upon it early in the morning of the 10th inst. with the whole of the Army. The position proved far stronger than was anticipated, and the enemy made a most gallant and determined defence. After five hours most severe fighting, in which our troops were three times repulsed, we at last stormed the position, driving the enemy headlong into the river, which ran immediately in their rear. Such a hard fought battle could not of course be gained without considerable loss on our side—but it is far less than might have been expected, and has been confined in general to but a few Regiments. Mine unfortunately has again been a most severe sufferer; poor Taylor, our Colonel and who commanded the Brigade in which the 29th were, was shot dead when gallantly leading the advance; in addition to which calamity we had ten other officers wounded, some of them very severely, and had 45 men killed, and 87 wounded. Our poor Regiment is now a complete skeleton, having lost by killed and wounded in the battle of Ferozeshah and this last action nineteen officers out of twenty-eight, and 370 men out of 730 that we brought down from Kussolie. Poor Taylor's death will promote me to the Lieut.-Colonelcy of the Regiment, which is a great piece of good fortune for me, but nevertheless I would rather have retained the friend and lost the promotion than it should be as it is. We have this time followed up our successes by crossing the river in hot pursuit of the enemy who have fled with precipitation to Lahore, and where probably our Army will again come up with them. I don't imagine they will stand before us for another fight, as they have now lost 236 pieces of cannon and the whole of their Army is nearly annihilated. It appears to be the general opinion that they will sue for peace, and that certain terms will be grated them in which case our Army will return to this side of the River, and break up before the hot weather sets in. God grant that it may be so is I think the prayer of every European in the Army.

With kind love to all at home, believe me, Your ever affectionate son,

GEORGE CONGREVE

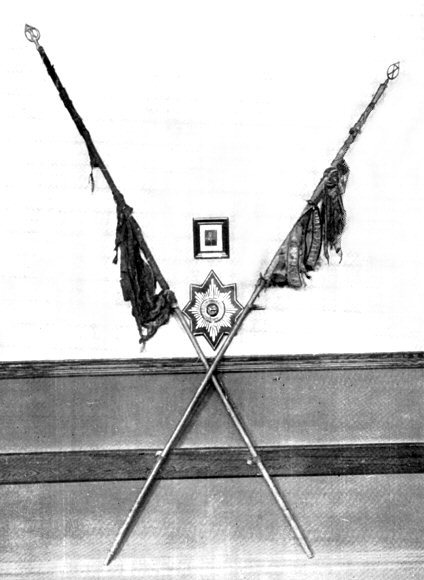

The Colours of the 29th Foot which were carried in the Sikh Wars The pole of the Regimental Colours is shorter than that of the King's Colours, since the foot of the pole was shot away in the Battle of Sobraon |

THIRD LETTER FEROZEPORE, FEB. 28TH, 1846. I am rejoiced to tell you that at last I have left my bed, and taken to walking about on crutches. I am, however, dreadful lame, and like to continue so for many months for I cannot even yet bear to touch the ground with my foot. I also at last, with mingled sensations of pleasure and grief, am able to tell you that I am now Lieut.-Colonel of the 29th a piece of good fortunate that fell to my lot on the 11th of this month, by the melancholy death of poor Taylor who was killed in the fierce and bloody battle of Sobraon on the 10th instant where my unhappy Regiment left on the field of battle one half of its numbers, among them being 13 officers wounded, three of whom have since died of their wounds. The victory as you will read in the newspapers was a glorious one, and ended in the total overthrow of the entire Sikh Army; the carnage on their side was truly horrid, the river Sutledge being literally choked up with their dead; their loss is estimated at the lowest computation to have been 10,000 men killed, and drowned. Poor Taylor on that memorable day, fell, shot through the head, leading on his Brigade against the enemy's fortifications in the most noble and gallant manner; he died the death of a soldier, beloved and esteemed by all and it grieves me to the soul to think that to his death I owe my promotion, such is war, and its dreadful attendants. I have had enough of it. Two days after the action our victorious Army crossed the Sutledge in pursuit of the remnant of the Sikh Army, and arrived at Lahore without meeting any opposition. The Governor General is with the Army and is now dictating terms of a treaty to the Puniaub Government in their own capital, a glorious thing for the honour of Great Britain. I wish to goodness I was up there for I am miserable in being absent from my Regiment at the moment when our triumph is being displayed as conquerors of the Punjaub and avengers of treachery and bad faith, in a nation. Part of the Governor General's stipulations are, that the Sikh Government pay over to us three millions sterling as indemnity for the great expense the war has put us to. As soon as the whole of this money is paid up, our troops are to return, which is expected to be about the 10th of next month, when I trust we shall once more march for our delightful quarters at Kussolie. Having obtained the Lieut.-Colonelcy of the Regiment there will be much greater difficulty in my returning to England as formerly, as the Commander-in-Chief does not approve of both Lieut.-Colonels being absent from the Regiment and Simpson being certain never to return to us, I must remain where the Regiment is . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

FOURTH LETTER

KUSSOLIE, APRIL 25TH, 1846.

MY DEAR FATHER,

Your most kind congratulatory letter of the 28th Feb. reached me yesterday, and truly rejoiced am I to learn the value that you, in common with every other Englishman, set upon the services rendered to our country by the gallant "Army of the Sutlej" in the late campaign, which thank God is now brought to an end, for I do assure you I firmly believe that from the Governor General down to the humblest Sepoy, there is not an individual who does not rejoice at the termination of the most bloody and hard fought campaign, for the time it lasted, in the annals of Great Britain. You mention that my letter detailing the account of the battle of Ferozeshah has not reached you and that you are anxious to know most particularly what the 29th did, I must therefore tax my recollection and detail as far as I am able the account of our march from hence and subsequent engagements, on the 21st and 22nd December in which, however, I must necessarily appear to disadvantage as I must be my own trumpeter. It was, I think, on the evening of the 10th December when I was dining with poor Taylor that Captain Abbott, the Governor General's Agent in these Provinces, was announced, and much to our discomfiture and total destruction of an agreeable dinner party, announced that the Governor General had sent him express to bring down the Regiment to join the Army with the utmost dispatch. We accordingly marched the following morning at daylight, and on the 19th we joined the Army at 11 o'clock at night after a series of most distressing marches, averaging 25 miles per day through a heavy sandy country, with a great scarcity of water for both men and animals and the sun scorching hot during the day time, with a hard frost at night. We were only one day too late for the battle of Moodkee, which perhaps was fortunate for some of us. The 20th we were allowed to halt and rest ourselves, and much indeed we were in need of it for we were not only completely tired, but the men were beginning to grumble at the severe marching. On the morning of the 21st at three o'clock the whole Army was under arms, and marching to the "rendezvous" which was three miles on the road to Ferozepore. We were delayed at the rendezvous until nearly eight o'clock in the morning in consequence of a complete jumble among the Regiments. At last the Army being formed in order of battle we moved on and again halted about 12 o'clock to allow the men to eat what little refreshment they had brought with them; for myself and poor Lucas, who so shortly afterwards was shot dead close to my side, and whose blood was splattered all over me, we had a tough old hen and some sour bread with a bottle of raw brandy to wash it down, but not a drop of water to be procured for love or money; the brandy, however, was not so bad and under the peculiar position in which we were then placed was perhaps of service in more ways than one, as it kept the courage up at the sticking point. It was at this point we were joined by the Division from Ferozepore under Sir J. Littler, consisting of about 8,000 men, it was from this Division we first learnt that the whole of the Sikh Army amounting to nearly 60,000 men with 150 guns, many of them being 24, 32, and 36 pounders, were within three miles of us in a strong entrenched position. Our gallant old Chief Sir H. Gough in conjunction with Sir H. Hardinge then formed the plan of attack. They kindly decided that our Division, the 2nd, was to lead, and accordingly when we had advanced to within of a mile of the enemy the Army halted and having wheeled into line, we advanced in direct echelon of Battalions from the right flank. As my Regiment was on the extreme right I naturally felt extremely nervous and anxious, for upon me depended the eclat of the attack, and it being also the first time I had ever been in action I was not quite sure how I should conduct myself. In this extremity I offered up a short prayer to Almighty God to strengthen my understanding, and that if it was ordained that I should fall, that I might do so in all honour and glory at the head of the brave fellows I was commanding. I cast one glance upon the Regiment from right to left, and both thought and felt that nothing could surpass it, in either appearance or steadiness. At last the word "Forward" was given; not a syllable was uttered, and we moved to the attack with the silence of death. When within half a mile of the enemy our Artillery opened, in order to make them show themselves; the whole country being covered with a light jungle that interrupted our seeing their position. The challenge was immediately replied to, and in an instant they had a number of heavy guns pouring in round shot at us as fast as lightning, and the men going down in sections. The cannonade was so terrific, and our Horse Artillery guns so small a calibre being only six and nine pounders which were quite unable to silence the enemy's guns that we were obliged to lay down, and thus allow the shot to go over us. Our artillery, although admirably served, could do nothing against the superior weight of metal of the enemy; and the infantry were obliged again to advance against the Batteries supported by the Horse Artillery; there were twelve guns close to our right, but before we had gone 200 yards farther seven of them were hors-de-combat. The enemy served their guns in a manner that would have done credit to our Artillery at Woolwich; they altered the range as we advanced upon them to the nicest accuracy, cutting us up with every discharge; as we got nearer they substituted shrapnel for round shot, and when we were within 200 yards they loaded with grape, cannister and chain shot. Then began the work of death. Nothing daunted by the storm of iron that was absolutely hailing upon us, and dealing destruction through our ranks, we still moved on, and when at 100 yards from the mouth of the guns we opened our

musketry. In less than five minutes the battle raged in every direction, and the dust and smoke were so thick, that the sun looked like a London sun in a very thick fog. When within 50 yards of the guns we were brought to a check by their terrific fire ; the old 29th who had displayed such intrepid bravery began to waver, our fire slackened and the ranks became broken, in fact the Regiment was in a mass of confusion and all but giving way. In this dilemma I rushed into the mass and by means of entreaty, threats and example got them again into order, and placing myself in front gave the word "Charge," it was obeyed like magic, and with one right good British cheer, we made a dash forwards. As we reached the trenches, and I was on the point of jumping into them, I was shot through the ankle and unable to go any further. I, however, had the inexpressible satisfaction of seeing our noble fellows fighting hand to hand with' the enemy, and overcoming them in every direction. It was painful, however, to witness the gallant daring of one of the companies, who charged up to a 36 pounder gun, which fired upon them when ten yards from its mouth; nearly the whole of the company fell, twenty-seven of whom never again stirred; the gun had been loaded to the muzzle with grape and cannister, and the gunners reserved the fire until our poor fellows were close to it; not a gunner, however, of that gun was left alive, they were all instantly bayoneted by other men of the Regiment. The desperation with which the gunners fought was wonderful, they all died fighting with the most determined gallantry at their guns, and the infantry who lined the trenches behaved as well, they neither asked or gave any quarter. Immediately on our troops entering the camp it caught fire, and there being immense quantities of powder in every direction, we were obliged to retreat as quickly as possible as explosions were taking place every instant. Fortunately for me the 29th retreated by the same road that they had entered, and picked me up; I was then carried to the rear, and remained all night at the bivouac of the 3rd Dragoons where I found an old friend of William and mine, Hale. He was most kind to me, but unfortunately could not procure for me a drop of water, and I was dying of thirst. Never shall I forget that dreadful night; the frost was intense, and without anything to cover me, nothing to eat or drink, not having tasted either since 12 o'clock, the battle raging as fierce as ever, not half a mile off; the groans and screams of the wounded men, the neighing of horses, and the awful curses of sonic of the men, made me devoutly wish that I had been killed on the field at once. During the night the Sikhs had regained their camp, and when day dawned, the whole of the work of the previous evening had to be begun over again. The Governor General's dispatches will give you a better account of the proceedings on the morning of the 22nd than I can; I may, however, tell you what he does not, viz. that the Sepoys had almost all retreated and the only troops left to fight it out were the European Regiments who however did their work splendidly. The Sepoy Regiments behaved infamously, they almost all to a man ran away; the 45th N.I. who were brigaded with us had entirely disappeared, excepting the officers who joined us and fell in as if they formed part of the 29th. When the Sikhs retreated, which was about 2 p.m. on the 22nd, the Regiments were ordered to pile their arms and get what refreshment they could, for both men and horses were so completely worn out with fatigue and thirst, that we were totally unable to take advantage of our victory and pursue the enemy. There being only two wells in the neighbourhood you may readily imagine the rush that was made towards them for water by the whole Army which now amounted to about 15,000 men, as the Sepoy Regiments were again all complete, the men having returned as soon as the firing had ceased. We found in the enemy's camp an abundant supply of rice, flour, and grain of every description, and two bullocks having fallen to the share of the 29th they were very soon converted into beef, and never did poor mortals enjoy a meal more than we did that day. As soon as the enemy had retired our surgeon brought me up to the Regiment, and you may picture my happiness on our discovering when passing through the camp, a large quantity of beer in bottles that the Sikhs had plundered in the town of Ferozepore, and to which in our turn we helped ourselves largely, but some of the soldiers having discovered the prize, it was very soon all gone. There was also a quantity of champagne found and also brandy, but I saw nothing of either. It was in this camp that I came upon poor Egerton, who was lying on his face literally carved in pieces and his horse dead by his side. Our surgeon at first thought he was dead, but on his manifesting some signs of life, we got him some beer, and sent him on a litter to the village close by, where the wounded were being collected. I never could have believed it possible for a man to live, as he did for six weeks afterwards, with the fearful gashes he had received. I must not forget to tell you that the wells that supplied us with water, were full of dead Sikhs and horses, which the scoundrels had thrown in when they were driven out of their camp, yet notwithstanding that the water was putrid everybody drank it with avidity. Never shall I forget the taste of it as long as I live, or the greediness with which I drank all that I could get. On the morning of the 23rd after a quiet night, our surgeon got me an elephant, upon which I was sent into Ferozepore, and truly thankful was I once more to find myself on a bed although I was in excruciating agony. The remainder of my adventure you know, as you must have received some of my letters from the Ferozepore Hospital. On the 10th February my Regiment was again engaged in the bloody, but final, battle of Sobraon where we lost poor Taylor and some other officers and a host of men. I would have given worlds to have been present at that battle, as the victory gained was most brilliant. The Sikhs fought desperately, and when their ammunition failed, attacked our troops, sword in hand. They were at last, however, after the most gallant defence compelled to retreat, but when they attempted to cross the ford it was found, as if it was the act of Providence, that the river during the night had risen twelve inches, and in consequence, that excepting in one spot about 50 yards wide the ford was impassable. In this space, therefore, the whole of their Army had to mass, and our guns amounting to 70, with the whole of our infantry, having been brought to the side of the river, opened their fire upon the devoted mass of Sikhs, and in less than one hour 10,000 men were dead in the river. By those who saw it, I am told that the bodies of both horses and men were so thickly strewn that a man could walk across the river on them. To give you an idea of how severely my Regiment has suffered in the oampaign I enclose you a return of our killed and wounded. We left here on the 11th December with 28 officers and 765 men; out of the former number we had eight killed and twelve wounded, which is immense. You must know ere this of course that I succeeded poor Taylor as Lieut.-Colonel. It is the true way to be promoted on the field of battle, though there are always grounds of regret on such occasions, for many good men who fall. I must get you to tell William that the gallant conduct and daring of his old Regiment the 3rd Dragoons was the admiration of the whole Army. Nothing could exceed their magnificent behaviour. Our mutual friend Hale, was present in all the actions and was never touched, but had two horses killed under him. My Regiment is now I am happy to say safely again here and I trust it will be a long time before we are again called on to fight against the Sikhs. Pray thank all my relations and friends for their kind congratulations and enquiries, and believe me my dear father ever

Your affectionate son,

GEORGE CONGREVE.

Total killed and wounded at Moodkee, Ferozeshahur, and at Sobraon of H.M. 29th Regiment |

|

| KILLED | WOUNDED |

| 8 Officers | 12 Officers |

| 5 Sergeants | 13 Sergeants |

| 142 Rank & file | 255 Rank and file |

FIFTH LETTER

KUSSOLIE,

UPPER PROVINCES,

MAY 21st, 1846.

MY DEAR WILLIAM (his eldest brother),

Your letter of March 17th was received by the last mail, but I am so much occupied in reorganizing my Regiment that I have not half an hour to devote even to thinking of my friends much less writing to them. You must not therefore feel disappointed at receiving only a few lines in reply. The direction you give me I cannot decipher; I therefore send this to Bristol from whence it will be forwarded to you. I have written so much about the late Indian campaign that I am sick of the subject—you must therefore excuse my saying anything more about it, farther than that in action a man requires to have both his eyes and wits about him and that human nature at the sight of blood gets so savage, that all kinds of atrocities are perpetuated in the coldest blood, that at any other time one would shrink from with horror. I regret to have so bad an account of the Congreve affairs, for I had hoped better things; it has decided me upon remaining several years longer in India where my allowances now amount to 1700 per annum—from which sum I shall be enabled to lay by something annually. Simpson having gone to England totally precludes the possibility of my getting home to fulfil my engagement with Louisa Call, as the Commander-in-Chief will not permit both Lieut.-Colonels to be absent from India at the same time; if therefore our marriage is ever to take place, she must come out to this country, as I cannot go to fetch her. This is a most painful situation for both her and myself, but what can be done to remedy it? Your old Regiment immortalised itself in the late campaign; at Ferozeshah they did such good service, that at the close of the action, in their last charge they had only 75 troopers on horseback. Our mutual friend old Slade distinguished himself particularly and although present at Moodkee, Ferozeshah, and Sobraon, was not touched. He has been staying with me for the last ten days, and we had long talks about olden times in which you were not forgotten; he desired particularly to be remembered to you, he is a thorough honest, good fellow, and we are great friends. I forgot to tell you that little Balders had a narrow escape at Ferozeshah—a round shot having grazed his stomach; he suffered so much from the bruise that he nearly died afterwards, he is, however, now quite well again. I strongly recommend you if ever you have an opportunity to get one of your sons, or more if possible into the Civil Service in this country, it is the finest appointment possible. He would commence with a salary of 35£, per month—and if he exerted himself and was tolerably clever, he would in a very short time rise to 50£, and 70£ from which he would gradually increase up to 250£ and 300£ per month—retiring after 23 years' service upon 1000 pr. ann. exclusive of his savings, which ought to bring him at least another 1000£, per annum. I do not by any means advocate the military service, it is bad throughout, excepting the Engineers 'and Artillery; and had I twenty sons, I would not allow one of them to go into the E.L.'s infantry; where the promotion is wretchedly slow and the society ungentlemanlike, with kindest remembrances to Selina believe me very affectionately yours

GEORGE CONGREVE.

P.S.— I forgot to say that I am still on crutches, and that my wound remains open, in spite of the advantages of this fine hill climate. I much fear I shall be lame for many months, if not for ever.

SIXTH LETTER

"ARMY OF THE PUNJAUB"

CAMP NEAR RAMNUGGUR,

ON THE BANKS OF THE CHENAB.

DECR. 31ST, 1848.

MY DEAR FATHER

I was in hopes that by this mail I should have been able to have written that the campaign was at an end or nearly so, but I regret to say that the conclusion of it is apparently as far off as the day it began. On the 22nd of last month we came up with the enemy at Ramnuggur where our Cavalry and Artillery were sharply engaged with them for 2 or 3 hours but without gaining any great advantage over them. To us I cannot but consider that the affair was most disastrous for we lost two of our very best officer's, General Careton and Colonel Flaselock, both of whom were my most intimate and sincere friends and whose loss I deeply deplore, the former especially. Our loss on that day was small in numbers and that of the enemy about treble of ours. We succeeded, however, in driving them across the Chenab where they had a strongly entrenched camp and where they made a stand with their batteries commanding the only two fords of the river which most effectually prevented our pursuing them. We certainly might have forced the passage, but in doing so we should have been exposed to such a terrific fire that we must have lost thousands which with our present small Army we could not have afforded. From the 22nd to the 2nd of this month we were actively employed erecting batteries in our front for our heavy guns, so that they might cover our attack when crossing the ford, during which time our camp was immediately opposite to that of the enemy and only about three miles space between us so that with a good telescope we could see them distinctly. When erecting our most advanced batteries we were so close that the shot from their guns continually fell among us, but we sustained little or no loss from them. On the night of the 1st, having sent Sir J. Thackwell with a strong force of all arms higher up the river for the purpose of crossing and taking the enemy in flank, we opened our heavy guns in front on the morning of the 2nd upon the camp and position of the Sikhs from which they suffered most severely. In the meantime Thackwell having effected the passage of the river came down upon their flank, upon which they advanced to meet him and an engagement took place but which was confined chiefly to the artillery. In three hours the Sikh guns were silenced and their loss in killed and wounded very heavy, ours not exceeding seventy but from some unaccountable blunder and infamous generalship of Sir J. Thackwell's instead of attacking instantly with his whole force, he allowedthe enemyto retire, and before he could rectify his error night came on, when all chance of annihilating the enemy, which could have been done at first, was gone. Had he advanced the Sikhs must have lost all their guns and their whole Army been cut to pieces which would have terminated the campaign. Unfortunately the ford of the river in our front was too deep to admit of our joining Thackwell on the 3rd in consequence of the river having risen two feet from a heavy fall of rain on the night of the 1st. The enemy have now taken up another strong position about 12 miles in our front, and upon this side of the Jhelum where we shall, I believe, attack them as soon as news of the fall of Mooltan reaches the Commander-in-Chief, which we may expect in about ten days. Our battle will, I am afraid, be a very hard one as the Sikhs have now an Army of 40,000 men and sixty guns. We have not more than 17,000 men, but we are better off for artillery than they are, having seventy-five guns well manned and plenty of ammunition; and as artillery is a thing that natives cannot stand, I trust we may obtain a victory comparatively easy to those we gained in the Sutlej campaign, when the enemy had Such a superiority in guns, as you are of course aware.

Should I be spared in the approaching battle I will write you instantly of my safety, and, I trust in God, of the success of our arms.

With the kindest love to all of my family, believe me, my dear father,

Ever your affectionate son,

GEORGE CONGREVE.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Letter from Major Way (2nd in Command) to Capt. William Drake, late of the 29th Regiment, in England.

CAMP, JAN. 14TH, 1849.

MY DEAR WILLIAM,

On the day this reaches you fill a bumper of the best to the old 29th who have once again been in action and greatly distinguished themselves, I certainly never felt so proud of having "29" at my masthead as I did, when immediately after the action as I was scouring the bushes with a party of 70 men to pick up our poor wounded fellows, I came upon Lord Gough and all his Staff, together with other officers of various corps, and the shaking of hands I then came in for spoke stronger than any language could have done their opinion of the Regiment. The old Chief himself saying the 29th have this day been the admiration of every soldier of the Army, and that to his last day he should never forget their gallant bearing." And from what I afterwards heard of the failures that took place in other parts of the field there is no doubt but that the dashing en avant charging of the old Corps in every direction where there was a gun, or a body of Sikhs to be upset, must have contributed greatly towards the victory. This being the last day for the overland I must attempt to give you a short description of the affair, but from having been on the qui vive since 6 a.m. yesterday my despatch will not be a very lucid one. Yesterday morning at 6 o'clock we struck our tents, and at 7 began our march from a village called Dinghie supposed to be some 10 miles from the enemy's position. We moved in mass at quarter distance columns right in front and as the 29th was the right battalion of our Brigade we had the post of honour, the 56th N.I. being the centre, and the 30th N.I. the rear battalion.

| H.M. 61st | Guns | H.M. 24th | Heavy guns | H.M. 29th | Guns | 2nd European |

| N.I. | — | N . I . | dragged | N.I. | — | N.I. |

| N.I. | — | N. I. | by elephants. | N.I. | — | N.I. |

| —————————————————————————— | —————— | ————————————————————————— | ||||

| 3rd or Gen. Campbell's Divn. | 2nd or Gen. Gilbert's Divn. | |||||

| Cavalry | Cavalry | Cavalry | Cavalry | Cavalry | Cavalry | |

In this way we proceeded for 5 miles direct across the country towards the enemy's position (the ground being not exactly an open country but jungly) when we approached their first outpost, which after cannonading for half an hour, was carried without loss by the light bobs of our Brigade; shortly after this the several Brigades were ordered to deploy into line, a movement no sooner made, than the round shot came hopping about and over us, but, as the men were ordered to lie down, this firing, though continued for upwards of an hour, did little or no damage ; our guns had in the meanwhile advanced some 200 paces in our front, returning shot for shot. At last the Commander-in-Chief rode along the front of the line ordering the advance. We moved off in quick time, the Brigade keeping a capital line for the first half-mile, when the fire which had been gradually getting up its steam, now burst upon us with a vengeance, throwing our friends the N.I. into pretty considerable confusion, but bringing the longed for word—Charge—out of our Brigadier Mountain and "By your Colours, 29th!" from Congreve. Onwards we dashed through the underwood, and in five minutes from the word—Charge¬had captured a park of 12 very prettily appointed brass guns together with a large howitzer, the artillerymen surrendering their charges with their lives; our men fortunately now got just breathing time allowed them before we descried a large body of Sikhs approaching through the brushwood for their recapture and firing into us with every description of small arms; however, one volley, followed by the charge made them think better of it, and when we got within 60 yards of them, away they bolted, faster than we could follow; as we were now considerably in advance of the rest of the Army, it was a case of pull up, but almost at the same moment another battery on our left commenced raking us with grape, so changing direction on the light company by throwing forward our right, off we started at the charge, and at 200 yards came suddenly upon what we wanted, they must have been precious quick in getting off their guns, for we only found one left in the position, the gunner of which coolly bestowed among us his last round of grape when we got within 30 yards; this was the last we had the honour of capturing and for the next half-hour, our fellows had some splendid firelock practice, for owing to our having got so far to our front, we were fairly surrounded by Sikhs who were crawling back again from bush to bush taking pot shots at us from front, rear, and flanks, just in the way I have seen poachers at work in the woods at home. This battle continued till we perceived Campbell's Division approaching on our left flank, when the firing in every direction ceased as if by magic, and we could see the enemy running away by thousands over a fine open plain, taking guns, wounded, &c. along with them. Had our cavalry been now brought to the front, Lord Gough must have won a victory that even he might have been satisfied with retiring on, but as it was, not a horseman of our Army that day ever got to the front, and from all sides we heard they had been beaten back by the Sikh cavalry.

I am required on duty.

Ever yours, my dear Drake,

GREGORY WAY:

(The above is a copy of Major Way's letter to Captain Wm. Drake late of the 29th Regiment.)

William (Drake) says "I showed it to Lord Strafford who took it to the Duke, he carried it off home and returned it the following day, expressing himself much pleased with the Regiment, and with the letter, which he said was a very good one (no slight praise to get out of him). Lord Strafford is also very highly pleased with the Regiment and desired me to say so. In fact the letter has been handed round to all the great people, and praise from every one has been given to the old Regiment and it must be highly gratifying to our old friends to know that all this has happened under Congreve's command."

(The above is an extract from Mrs. H. Lloyd's letter to Aunt M—.)

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

FROM THE " BOMBAY TELEGRAPH & COURIER "-FEBRUARY 7TH, 1849

"Some letters from an officer who took part in the sanguinary conflict of the 13th ultimo, have been obligingly placed at our disposal which afford a few particulars of the behaviour of the troops in action, which we have not as yet seen so fully given elsewhere and which therefore we may advantageously lay before our local leaders. Touching the conduct of H.M. 14th Dragoons, it is stated that the men of that Regiment are declared even by their own officers to have conducted themselves most discreditably; they went 'threes about' and fled in great disorder; whether in compliance with Brigadier Pope or not, is a point to be decided between them and that commander—certainly the latter would never have ordered them to ride through our Horse Artillery guns and up to the Field Hospital—the 30th and 56th N.I. are said to have advanced splendidly, but the terrific fire threw them into confusion, they got clubbed into masses 20 deep, when they were shot down by scores, and fired in the air, and, what was worse, into the 29th Regiment. Had it not been for their great intrepidity they would have been annihilated. One squadron of the 3rd Light Dragoons was conspicuous for gallantry; they charged through the Sikh Cavalry and back again. The lamented Major Christie (a notice of whose death appears in our obituary this morning) is said to have 'declared solemnly on his death bed, that if the 14th Dragoons and 9th Lancers had supported his guns they would never had been lost.'—the 6th Cavalry fled to a man. It is stated that Sir J. Thackwell ought to have brought up the cavalry in a mass to support the infantry which he might easily have done, as the ground was not unfavorable to the right, for the mounted arms to act, both Generals Campbell and Gilbert behaved nobly—Colonel Congreve of H.M. 29th shot one Sikh, cut down another, and took a gun unassisted. No bridge had ever been built by the Sikhs across the Jhelam, and it is said they would not allow the Shere Singh to construct one for fear he might retreat. So great was their bravery that at one time they actually charged into the line of Sepoys and cut down many of them. The general opinion was that the expected junction of Chutten Singh with his son's Force, might induce the latter to take the initiative and attack Lord Gough. Dost Mahomed, it was believed, had given out that his object in the capture of Attock was merely to prevent the Sikhs taking the place."

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

(Copy of a Letter from Lady Napier to George Birch.)

NASCOTT,

JUNE 13tH, 1849.

MY DEAR GEORGE,

On our arrival here yesterday I found your note of May 27th and Sir George begs me to say that when he next writes to his son (who is with his uncle in India) he will mention your nephew, Mr. Wm. Congreve to him, and request that if an opportunity offers he will make him known to Sir Charles—at the same time he desires me to add that the young man's uncle now in India is so well known to Sir Charles by his own merits and services that he can have no better recommendation to the Commander-in-Chief than being the nephew of Colonel Congreve.

With our united kind regards to you and Mrs. G. Birch. Believe me, yours most truly,

(Signed) F. NAPIER.

From: Major-General Sir W. R. Gilbert, G.C.B., Commanding the Punjaub Division of the Army,

To: Lieut.-Col. George Congreve, C.B., Commanding N.M. 29th Regiment.

Nothing can afford me greater pleasure than to bear testimony to the gallant conduct of a gallant Regiment, and to the able leading of its Commander, Lieut.-Col. George Congreve, C.B., who at the head of H.M. 29th Regiment attached to the Division under my command both in the Sutlej and Punjaub campaigns, evinced in every action in which his Regiment was engaged a very high degree of coolness, presence of mind, judgment, and personal courage, especially in the hard fought battle of "Chillianwalla," in which the Brigade under Brigadier Mountain, to which the 29th Foot belonged, was nobly engaged, and this admirable Regiment led by Col. Congreve highly distinguished itself in breaking through the centre of the enemy's line, and carrying everything before it. I witnessed the first advance of the Regiment against a battery of twelve guns, and I was particularly struck with the manner in which Lieut.-Colonel Congreve restrained his men (eager as they were for the coming struggle and anxious to close with the enemy) until their line, disordered as it had been by heavy jungle through which it had passed, was properly reformed, two deep, and ready to move on when the Battery was brilliantly carried and its guns spiked.

The flank of my right Brigade being threatened at this time, left Col. Mountain's Brigade to give my attention to it, and was thus prevented from seeing the noble deeds subsequently performed by the 29th Regiment, but Col. Mountain reported that it continued to drive the enemy before it, that having got in advance of the rest of the Brigade, and the enemy pressing on its left flank, it charged front, and repulsed him, that it captured four guns brought to bear on it with grape, and that when again hard pressed by the enemy, it faced about and fought rear rank in front. In short that for three hours it continued its course of victory, leaving 35 men killed and 205 wounded. I had previously seen the brilliant conduct of the 29th in advancing before the enemy's batteries at "Ferozeshah," and "Sobraon" and its continuance in such a gallant career I attribute to the judicious management and able leading of Lieut.-Col. Congreve.

(Signed) W. R. GILBERT, M.-General, Commanding the Punjaub late 2nd Division of the Army of the Punjaub.

LAHORE,

10TH NOVEMBER, 1850.

From: Brigadier A. H. Mountain, C.B., Commanding 4th Brigade of the Army of the Punjaub.

To: Lieut.-Colonel Congreve, C.B., Commanding H.M. 29th Regiment.

Her Majesty's 29th Regiment served in the 4th Brigade of the Army of the Punjaub under my command during the campaign of 1848-9. I can bear witness to Lieut.-Col. Congreve's energetic discharge of his duties as the Commanding Officer of the Regiment throughout, and particularly at "Chillianwalla" where he was most prominent in cheering on his men, during an arduous struggle through upwards of a mile of thorny jungle, in which the Regiment was continually exposed to a heavy fire of grape, round shot, and musketry. This gallant Regiment under the command of Lieut.-Col. Congreve, C.B., after repeatedly opening fire and repeatedly charging, took every gun in its front and attained the foremost point in the field, having driven the enemy from his cover of bushes and trenches, and silenced all opposition.

(Signed) ARMINE H. MOUNTAIN, Colonel, H.M. Adjutant General in India, late Brigadier Commanding 4th Brigade of the Army of the Punjaub. HEADQUARtERS CAMP,

KHURURIE,

24TH NOVEMBER, 1850.

JANUARY 2/52.

MY DEAR CONGREVE,

I cannot allow you to leave us without expressing the regret which I feel in losing an officer whose gentlemanlike and honorable bearing upon all occasions represented the most salutary example to the Force and upon whose opinion upon every subject connected with the public service I could place the utmost reliance. I earnestly trust that your release from official duty and your removal to a more genial climate will be the means of restoring your health which has suffered much for a long course of time. With my kind regards to Mrs. Congreve.

I remain, my dear Congreve, very faithfully yours, (Signed) D. M. GREGOR.