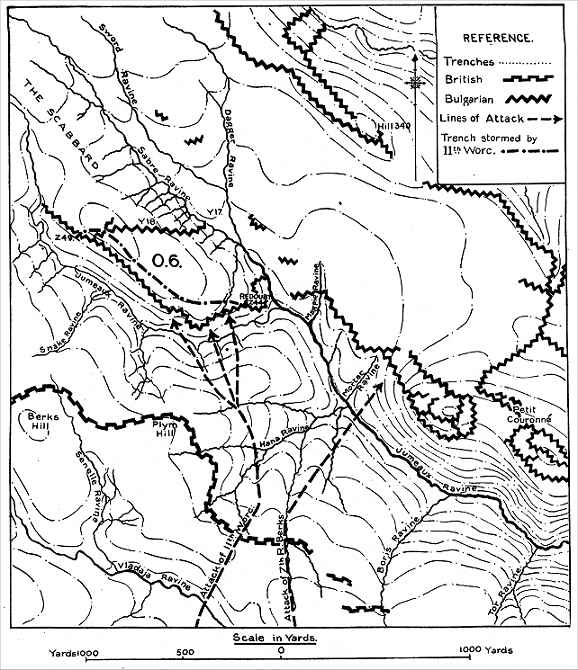

Macedonia 1917 (The 11th Battalion Worcestershire)

In Macedonia, it will be remembered, the winter of 1916-17 had closed down upon deadlock as complete as that on the ‘Western Front’. After completing their conquest of Serbia, the Bulgarian forces had entrenched themselves strongly among the mountainous ridges of the former Serbo-Greek frontier. In front of these entrenchments the advance of the Allied forces had been brought to a standstill; and after some minor operations both sides had settled down into what were virtually winter quarters.

The severity of the Balkan winter kept both sides immobile during the months of January and February. During those months the 11th Worcestershire alternated between the forward trenches near “Horseshoe Hill” and the reserve trenches near Chuguntsi. There was very little to choose between the two sets of trenches as regards discomfort and but little to choose between them as regards danger. Shell fire was only spasmodic, and patrolling brought little loss. The only active operation during this period was a raid carried out on the 11th February 1917, by the 10th Devons, on the right flank of the Battalion, against the Petit Couronné; which brought the 11th Worcestershire much excitement but fortunately no casualties.

Battalion was in forward trenches on dates as follows :—

3rd to 11th January 1917 - Casualties, 1 killed, 4 wounded.

20th to 27th January 1917 - Casualties, 2 killed, 1 wounded.

19th to 27th February 1917 - Casualties, 1 killed, 5 wounded.

5th to 12th February 1917 - Casualties, Nil.

7th to l4th March 1917 - Casualties, 2 wounded.

On the evening of February 27th a hostile air raid had most unhappy results for the Battalion. Three bombs fell in the lines of the Battalion transport, killing or wounding 52 animals and 19 men (37 mules and 1 horse killed, 12 mules and 2 horses wounded, 2 men killed. 2 died of wounds, 15 wounded).

In March the weather improved and the Allied forces prepared for active operations. Some readjustment of the front took place. The 26th and 22nd Divisions exchanged positions, and on the 24th March, after ten days of training in reserve, the 78th Brigade shifted its front to the east. The 11th Worcestershire took over trenches half-a-mile to the east of those previously held, facing down into the Jumeaux Ravine.

That Ravine is a steep cleft in the hills. Its precipitous slopes are covered with rough scrub. The hill tops are bare and rocky. The northern side of the Ravine, held by the Bulgarians was steeper and also slightly higher than the southern side. The Bulgarian line included a distinctive summit known as the “Petit Couronné” which was strongly entrenched and formed an important tactical point in the enemy’s main line of defence along the further side of the Ravine.

The left flank of the Battalion rested on a little gully known as the Senelle Ravine. The companies in their new position received a certain amount of attention from the enemy’s artillery, but the trenches were well sited and casualties were not very heavy (24th to 3lst March. Casualties, 3 killed, 5 wounded). On the evening of March 31st the 11th Worcestershire were relieved by the 9th Gloucestershire and moved back into reserve at Pearse Hill. There training was busily continued until, seven days later, preliminary orders were received for battle in the near future. The 22nd and 26th Divisions were to attack the enemy’s positions.

The attack was to be preliminary to a general Allied offensive astride the River Vardar. The enemy’s reserves were first to be attracted by the British attack on Doiran, and then the French would deliver the decisive attack further west. That intended extension of the plan was not communicated to the British troops; but they received long and detailed instructions for their own operation, to which further details were added at intervals during the ensuing fortnight.

Pending the battle, the normal routine of the Division was continued. On April 8th the 11th Worcestershire relieved the 9th Gloucestershire in the front-line trenches and held them till April 13th. As if sensing the coming attack, the enemy’s artillery was now more active, fortunately without serious results (Casualties from 9th to 13th April, 1 man killed). After relief on April 13th the Worcestershire marched back to camp at Pivoines. There six days were spent in strenuous training. Then on April 21st the Battalion moved forward to the line, and was accommodated in shelters prepared in the Senelle and Elbow Ravines, close behind the front trenches. Already the British artillery had begun (April 21st) a systematic bombardment of the enemy’s wire and trenches.

During those days before the battle, much good work was done by the Battalion Intelligence Officer, 2/Lt.

T. Featherstone; who carried out a daring reconnaissance of the enemy’s position, going out alone by night and remaining all the next day under cover close to the enemy’s line, thereby gaining most valuable information. He was awarded the M.C. for his actions.

On April 23rd came word that the attack would take place on the next night.

The plan of the attack, so far as the 26th Division was concerned, was a direct frontal attack across the Jumeaux Ravine. Further to the left the 22nd Division would advance from” Horseshoe Hill” along the ‘P” Ridge (so called because various tactical points along it had been designated” P.3,” “P.4,” “ P.5,” etc.), of which that height is the southern end.

From Lake Doiran to the Petit Couronné the attack of the 26th Division would be made by three battalions of the 79th Brigade; from the Petit Couronné to the junction with the 22nd Division two battalions of the 78th Brigade would make the attack, these being, from right to lift, the 7th Royal Berkshire and the 11th Worcestershire.

The objective of the 11th Worcestershire was a spur named on the maps “O 6.” On that spur the enemy were strongly entrenched. To reach those trenches the attacking companies would have to rush down the steep slope to the bottom of the ravine and then scale the equally steep slope on the other side. It was not expected that success would easily be won; for the Bulgarian infantry had proved themselves to be good fighters. As to the strength of the enemy’s artillery there was but little information.

The attack was timed for 9.45 p.m. The British heavy artillery, which had kept up a steady fire during the previous three days, continued firing without intermission through the twilight and throughout the first hours of darkness. The boom of the guns and the crash of the bursting shells echoed and re-echoed among the deep ravines.

The Battle of Doiran, 1917.

About 9.0 p.m. the enemy’s gun fire, hitherto not very noticeable, increased in intensity. Shells burst all along the British side of the Jumeaux Ravine, but the troops were in good cover and little harm was done.

Close on half past nine a series of red Very Lights shot up one after another from the enemy’s lines. Eight or ten lights were counted. The crouching troops wondered if it were a signal; but the enemy’s fire did not sensibly increase. Five minutes later the enemy’s gun fire seemed to die down.

Battle of Doiran (1917) |

Scarcely had that fact been noticed when at 9.35 p.m. the British field guns opened their ear-splitting shrapnel barrage. Ten minutes later the officers’ whistles rose shrill amid the din. The attacking platoons scrambled from their trenches and plunged down the slope. The attack had hardly started when three searchlights flashed out from the opposing heights and swept the slopes of the Ravine with their cold rays. Then the enemy’s barrage came down in full force. The strength of the Bulgarian artillery had not been suspected, in that mountainous country guns were easily concealed, and the counter-battery work of the British artillery had not been sufficiently effective. A tornado of shells struck the scrambling troops. So fierce was the fire that the supporting companies of the Royal Berkshire were cut off from those in front and never reached them; but through the storm the Worcestershire platoons made their way across the Ravine and up the steep slope opposite. Rifles and machine-guns from the Bulgarian trenches hailed bullets on the survivors as they struggled up through the rocks and scrub. Most of the front line were shot down, and for a moment the advance was checked. The survivors clung on as best they could, firing up at the flashes of the enemy’s rifles above them. Captain A. R. Cooper, commanding the leading company, realised that unless reinforcements came up the attack must fail. He dashed back into the midst of the shells, which were bursting at the bottom of the ravine, and there found the supporting platoons; these had lost direction and were, for the moment, dazed and bewildered by the darkness and the shell fire. He led them up the slope to join the survivors of the leading wave. |

Again and again Captain Cooper dashed back into the barrage and led forward his men. He was severely wounded, but continued to direct and to assemble his men until at last sufficient numbers had been gathered on the slope to make an assault possible. Then he gave the word and the line scrambled upwards through the scrub till they reached the Bulgarian trenches. A fierce fight followed in the darkness. The Worcestershire lads were not to be denied, and in a few minutes most of the enemy’s front line along the “O 6” Ridge had been taken with the bayonet. In the assault Captain Cooper was again severely wounded, but he refused to leave the fight until he bad seen the enemy’s front line secured. For his courage and fine leadership on this occasion Captain Cooper was awarded the D.S.O.

On the right of the captured trenches a strongly fortified redoubt (“ Z 44 “) at the apex of the spur beat back all attacks for some twenty minutes. During those twenty minutes the Worcestershire platoons further along the line worked desperately at the consolidation of the captured trench, urged on by Lieutenant S. A. Stephenson who, although already severely wounded, continued to command and inspire his men. Lieut. Stephenson was awarded the M.C. Then over the crest of the ridge came the first counter-attack; a hail of trench-mortar bombs, followed by a rush of yelling foes through the darkness. The attack was met by rapid fire and driven back. The enemy sent reinforcements from the rear into the redoubt on the right flank, and from that point commenced to bomb along the trench. They gained some twenty yards; then the Worcestershire bombers, headed by Private B. Harris, established a block and held firm. Pte. B. Harris, L/Cpl. G. Harrold and Sgt. W. J. Blood, were all awarded the M.M. Away on the left flank an attempt was made by a small party of the Worcestershire to bomb along the communication trench (“ Y 18 “) which ran across the spur. In that endeavour Lance-Corporal G. Harrold showed the greatest bravery. Under heavy fire from the enemy’s trench-mortars he led a squad of bombers along the enemy’s trench. Though wounded he continued pluckily to fight until finally disabled by a second wound. Gradually that attack along the communication trench was brought to a standstill; bombs began to run short and the enemy’s bombers, amply supplied, gradually gained ground. The survivors of the bombing attack were compelled to fall back down the communication trench and out on to the slope of the ravine beyond. There they were rallied by Sergeant W. J. Blood. Sergeant Blood was now commanding a platoon, for his officer had been killed. He led his men forward to a renewed attack, reoccupied part of the communication trench and held it thenceforward against all counter-attacks. |

Captain A. R. Cooper DSO |

The enemy’s trench-mortars from beyond the ridge (in the Sabre Ravine) kept up a continuous fire. Their great bombs fell continuously all along the line of the captured trench. The watchers in the British trenches on the far side of the ravine could see the showers of sparks from the flying bombs before the blaze of their burst. The watchers saw also another point of light in the captured trench - the glow of a signal lamp. The Battalion Signal Officer, 2nd Lieutenant L. C. Ryder, had led forward a party of his men through the barrage and up to the enemy’s position. The subaltern was killed, but Corporal H. Evans took over command of the signal party. A lamp was got up and a station established. In the midst of the desperate fighting and firing all around, and amid the continual bursts of the enemy’s bombs and shells, Corporal Evans coolly maintained communication with the other side of the ravine. From the British trenches his lamp was watched throughout the battle, a tiny point of light showing with its Morse dots and dashes, amid the blaze of the explosions. Corporal Evans was awarded the M.M. for his brave actions.

Information was also sent back by means of flares on a prearranged system. In the lighting of those flares Captain B. Baden did excellent work, showing great courage and resource and was awarded the M.C.

All along the valley the enemy’s shells were raining down. The bottom of the Ravine was filled with dense smoke lit only by the bursting shells. Through the smoke and up the steep slope came struggling the reserve companies of the Worcestershire. They had lost half their number by the time they reached the captured trenches, but the remnant flung themselves into the fight and became intermixed with the leading platoons. All did their utmost to make the position secure. A young officer, Lieutenant G. Thomson, who had been severely wounded early in the fight, had been sent back across the ravine to the British trenches. As soon as his wound had been dressed he at once set off again to find his platoon. He recrossed the ravine, found his men, and took in hand the work of reorganisation.

Hardly had that reorganisation been completed when, shortly after 1.30 a.m., came a fresh storm of shells and a fresh onslaught from over the ridge. The enemy were determined to recapture their lost trench; they had paused only to collect their forces and to arrange a fresh barrage with their overwhelming artillery.

That fresh barrage wrecked the defences of the shattered trench, and the new Bulgarian attack found the defenders with bombs exhausted and Lewis-guns mostly out of action. The platoons were now hopelessly intermingled, and in the darkness control was very difficult; nevertheless, inspired by the example of the wounded Lieutenant Thomson, the Worcestershire lads fought splendidly, beating off two more successive attacks.

Lieut. Thomson and 2/Lieut. Shaw were awarded the M.C. At that stage it was necessary to send back a message describing the position. Private J. Auden volunteered to take the message, and set out down the slope into the barrage. He ran the gauntlet of the shells successfully, reached Battalion Headquarters, delivered his message and returned with the reply. On the way back he was struck and badly wounded; but he struggled on, delivered the answer, and remained in action till the end of the fight. He was subsequently awarded the M.M.

A big bomb struck one Lewis-gun, killing or wounding all its team. Bombs were striking all around, but 2nd Lieutenant F. S. Shaw, although already wounded, got to the Lewis-gun and brought it into action. He worked it single-handed, shooting down many of the enemy as they came charging forward and encouraging his men to fight to the last. Further along the line Sergeant J. Harris kept a Lewis gun in action amid a shower of bombs by personally bringing up ammunition till he was hit and disabled. Lance-Corporal D. R. Payne took over another Lewis-gun of which all the crew had been killed and kept it firing until a direct hit by a bomb destroyed the weapon (Sergt. J. Harris and L/Cpl. D. R. Payne were awarded the M.M.).

At one point the enemy regained a part of the trenches. Sergeant F. Potter at once organised a counter-attack. Leading the attack himself, the brave sergeant drove the enemy from the trench and re-established the position. Then he reorganised the defence and took command of the situation, for all the officers of his company had been killed or wounded (Sergt. F. Potter was awarded the D.C.M.).

Throughout the battle the devoted Medical Officer of the Battalion, Captain J. P. Lusk, R.A.M.C., worked along the parapet of the captured trench. As fully exposed as any of the fighting troops, he tended the wounded where they fell. Among many brave men he stood out, in the opinion of all ranks, by virtue of his utter disregard of personal danger under that terrific fire. By a miracle he survived unhurt and continued his work of mercy to the end, assisted by a devoted stretcher-bearer, Private W. Keyte. Capt. J. P. Lusk was awarded the M.C. and Pte. Keyte was awarded the M.M.

The defence of the captured trench had been maintained for four hours, under constant fire and against repeated counter-attacks. More than half of the Worcestershire had fallen. Ammunition was almost exhausted. A message was sent for assistance. In response to that call a company of the 7th Oxford & Bucks L.I. were sent forward. Dashing through the barrage, some forty brave men of that regiment reached the position of the Worcestershire and bore a share in the last desperate struggle on the ridge.

About 3.0 a.m. came yet another attack. Three successive waves of the enemy came surging over the crest of the spur. In front the attack was stopped dead by the British musketry; but from both flanks the enemy’s bombers came pushing inwards, and no bombs remained with which they could be opposed. Gradually the length of trench held by the Worcestershire grew shorter, as from both flanks the enemy bombers pressed in. Unless help should come the end was only a question of time; but the remnant of the brave Battalion held on, until, about 4.0 a.m., there came a definite order to retire.

The Brigade Diary instances this order. It reads. . .“ as it became obvious that the small detachment which still held on could not hope to remain in daylight, this battalion (the 11th Worcestershire) was ordered to withdraw.” A subsequent passage in a Brigade report, however, suggests that this order from Brigade was anticipated by an order signalled from Battalion Headquarters in the British trenches. It is clear, at any rate, that the retirement was not initiated by the companies on the ridge.

All along the line to their right the attack had failed. The survivors of the other attacking battalions to the right of the 11th Worcestershire (away to the left the 22nd Division had gained ground, but their inner flank was half a mile from the” 0.6.” spur and could give no support) had already fallen back across the Ravine.

The order to retire was passed down the line, and, squad after squad, the remnant of the 11th Worcestershire fell back down the slope. Among the last to leave was Corporal A. Radcliffe who, on his own initiative, mounted a Lewis-gun on the parapet of the trench and covered the retreat of his comrades by bursts of rapid fire. Corpl. Radcliffe was awarded the M.M.

Those of the Worcestershire who still could move staggered back down the slope, turning and firing as they retreated. In the hollow below they found the remnant of two companies of the 9th Gloucestershire, who had advanced to their assistance but had been unable to pass the barrage. Still under fire, they hauled themselves up the further slope, through the scrub and rocks, back to their own lines, and reached at last the comparative safety of the British trenches just as dawn began to light up the scene.

The cause of the repulse was undoubtedly the terrific strength of the enemy’s artillery; greater by far than that of our own guns (Vide Divisional Diary—” A marked feature of these operations was the preponderance of the enemy’s heavy artillery over ours, which enabled him to place such a barrage on the Jumeaux Ravine as to upset our plans.”). The result was a mournful tale of casualties in all the attacking battalions. Out of a battle-strength of perhaps 500, the 11th Worcestershire had lost over 350 of all ranks. The losses of the other attacking battalions of the 26th Division were in much the same proportion.

Worcestershire casualties details:-

Killed or missing, 5 officers (Capt. H.Williams, 2/Lts. A. E. Gibbs, T. Featherstone, R. B. Lloyd and L. C. Ryder) and 105 other ranks. Wounded, 10 officers (Capt. A. R. Cooper, Lts. F. L. H. Fox, S. A. Stephenson, G. Thomson and H. R. Vance. 2/Lts. D. Brand, F. S. Shaw. R. M. Kirby and Captain F. S. Pearson (Dorsets, attached) and 238 other ranks; in addition. 1 officer and 27 N.C.O’s. and men, slightly wounded, remained at duty.

But though the attack of the 26th Division had thus met with disaster, the attack of the 22nd Division further to the left had been more successful. On that flank ground had been gained and the battle in that direction might be accounted a success.

The shattered battalions of the 26th Division could hardly be expected to realise that aspect of the engagement. The 11th Worcestershire lay all day of April 25th. in the shelter of Elbow Ravine, counting losses and bandaging the wounded. Next day the survivors of the Battalion marched back into reserve at Pivoines. There they remained, resting and refitting, while plans were made for a renewed attack.

To the westward the French were about to make a great attack beyond the River Vardar. To assist them, the British attack on the Doiran positions was to be renewed. The battalions, which had already suffered so heavily, were naturally not placed in the forefront of the new battle. On the 28th April the Battalion had been strengthened by a draft which, included the following officers - 2/Lieuts. F. Anderson, H. J. Fisher, H. S. Arundel, C. P. Oliver, D. G. Rankin and D. R. Gilliam.

The 11th Worcestershire were allotted to the Divisional Reserve, and moved on May 4th to bivouac behind Waterfall Hill.

On the evening of May 8th final arrangements were made for the renewed attack, and the 11th Worcestershire moved forward from Waterfall Hill to a position under cover in Bath Valley.

Once again the attack was made by night. The assault on the Petit Couronné was delivered by the 7th Oxford & Bucks L.I. From their right to the Lake three Scottish battalions renewed the attack across the Jumeaux Ravine.

Fortune turned against the attack. Though the night was calm and with a bright moonlight, a sudden change of temperature made an unexpected white mist rise from the ground and fill the Jumeaux Ravine. The mist, thickened later by the smoke of bursting shells, obscured everything to such an extent that in many cases the attacking companies completely lost their way.

Nevertheless the attack succeeded in gaining the opposing trenches. Then, as before, a series of counter-attacks forced the Scottish battalions back into the ravine. The 11th Worcestershire were ordered forward to their assistance. Arriving at the front line about 3.0. a.m., Colonel Barker found everything in confusion. No proper co-ordination was possible, and presently, after a gallant but unsuccessful fight, the 10th Black Watch fell back on to the position held by the 11th Worcestershire.

Colonel Barker, after considering the position as the dawn broke, came to the conclusion that an unsupported attack by his weak Battalion could have no good result. He reported his opinion to the Divisional Staff, and the Battalion received orders to stand fast.

When that order was received, the Battalion was in an exposed position on the forward slope. It was necessary to withdraw to a more covered position in rear. The enemy’s shell-fire was fierce and accurate, and the withdrawal proved very difficult. There was only one covered line of withdrawal among the rocks, and that was so narrow and precarious that at most only four men could go at a time, at intervals of about a minute. It took the Battalion nearly an hour and a half to withdraw in this manner. During that time the platoons awaiting their turn crouched in the shelter of a low bank. The enemy’s shells burst all along the line of the bank during that hour of waiting, but fortunately inflicted only a few casualties (The total casualties of the Battalion during the day’s operations were 1 officer (2/Lt. G. C. Brown) mortally wounded and 9 men wounded.). Eventually the last party, which included the Commanding Officer, and his Adjutant, Captain T. J. Edwards, made their way safely back to the covered position in rear, where the Battalion reorganized.

After the firing had died down the 11th Worcestershire marched back to camp at Pivoines. Next day the Battalion took over the front line (two companies in front line; two companies back in reserve camp) from the troops who had made the attack.

The battlefield was a grim sight. The whole of the fighting had taken place within the narrow Ravine, and its rocky slopes were littered with dead. In the renewed attack the 7th Oxford and Bucks L.I. had actually captured and held for a time the “ Petit Couronné”; and the bodies of many of their brave men could be seen lying where they had fallen on the very crest of the ridge. A few shells from either side still burst and echoed down the valley, but otherwise all was still.

The 11th Worcestershire remained in the front line for another ten days. Then came orders that the 78th Brigade was to be moved back and away to the quiet sector on the right flank of the British XIIth. Corps, east of Lake Doiran. The Battalion marched to the new area in two stages, and took over on May 22nd from the 7th Wiltshire a line of outposts on the high ground above Lake Doiran from Surlovo to Popovo. There the 78th Brigade was acting independently. The remainder of the 26th Division had been transferred to the left flank of the British line near the river Vardar.

The new sector was very quiet. In the valley to the northward the enemy held an outpost position along the railway line and the railway station of Yakinjali. Patrols from both sides went out at intervals; occasionally they met and fired. A few shells burst along the hill sides. Otherwise there was but little activity. In that comparatively peaceful area the Battalion reorganised A great part in this re-organization was played by Regimental Sergeant Major G. H. Dyke. For his good work in that capacity, and also as Battalion Quartermaster during the previous months, R.S.M. Dyke was awarded the M.S.M. For similar good work under great difficulties R.Q.M.S. G. Samson was awarded the D.C.M. Reinforcements arrived, and presently the 11th Worcestershire could again muster some 760 of all ranks.

In that area east of lake Doiran the 78th Brigade remained for some three weeks, and there the 11th Worcestershire were visited by the Army Commander, General Milne. He expressed his satisfaction with the Battalion and with the part played in the recent battle.

Then came orders for the Brigade to rejoin the 26th Division. On the 7th June the 11th Worcestershire were relieved, and marched by stages to Moravka, Hirsova, and the railway station of Caushitza. Thence on June 10th the Battalion moved into Divisional Reserve at Tertre Vert, and on the evening of June 14th relieved the 12th Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in the front line near Bekirli.

By that time the heat of the Macedonian summer had caused military activity to die down. Patrols and casual shelling were the only forms of hostilities, and neither occasioned many casualties.

After a fortnight in Corps Reserve at Kirec (between 18th to 31st July 1917), the 78th Brigade at the beginning of August took over the extreme left sector of the British line near Smol, next to the River Vardar. The 9th Gloucester-shire actually held the river bank, with the 11th Worcestershire on their right. The new position was held by the Battalion, alternating with the 7th Oxford & Bucks L.I. between forward and support trenches, throughout the Autumn and until the beginning of November. From 6th August, 1917 to 25th November, 1917, Colonel Barker was away sick. During this period Captain (A/Major) T. J. Edwards commanded the Battalion. There was little activity by the enemy, and there were but few casualties. During this period the 11th Worcestershire casualties were in August were, 3 killed, 1 died of wounds, 1 officer Lt. G. K. Crocker, and 4 men wounded. September, Nil and in October, 6 wounded.

But though the actual fighting and casualties were not severe, the troops in the Macedonian hills had a most trying time. By the middle of 1917 they had been for over a year in the forward zone. There had been no long rest and no possibility of leave. In those barren hills there were none of the comforts, which were possible behind the line for the troops on the Western Front. Billets were unknown: a “rest in reserve” meant a week spent under a bivouac sheet on a bare hillside. The absence of roads and railways and the great difficulties of transport in the hills made it impossible for any but the barest necessities to be brought up from the base (even mails were erratic; letters from England sometimes took six weeks). The troops often went short of fresh food and had little chance of any addition to their rations.

Such privations were not the only trial. Flies by day and mosquitos at night were a constant torment. As a protection against the latter, men going into the trenches at night had to cover every inch of bare skin. Veils to protect the face were worn over the steel helmets, and tucked into the jacket collar, gloves were worn to cover the hands, and the ‘shorts’ which the heat made necessary by day were fashioned with a turnover portion which could be tacked into the puttees at night. The climate, with its extremes of heat and cold, undermined the strength of all but the most hardy; and almost every individual of the Battalion sooner or later fell a victim to malaria. In such conditions it is no small tribute to the officers and men of the 11th Worcestershire that throughout that apparently interminable campaign they remained in good heart.

Early in November came a change of position. The French were extending their front and were taking over the eastern as well as the western bank of the River Vardar. When making arrangements for taking over the line the French Battalion Commander, who spoke no English learned that the British unit was the 11th Worcesters. “On hearing this he suddenly stopped and shouted with glee, ‘Lea-and-Perrins, Lea-and-Perrins!’ “.

The 78th Brigade was relieved by the French 122nd Division and, after a cheerful game of football in which they beat a French Zouave Regiment by 5 goals to nil, the 11th Worcestershire marched eastwards on November 7th to Kalinova. Thence the Battalion moved northwards to the line and took over trenches near Krastali from the 13th Manchesters.

The new line, close to the original position of the Battalion in the Doiran area over a year before, was an area of more active operations than that previously held. There were many minor

incidents in the work of the Worcestershire patrols and outposts, notably on November 16th when a patrol under 2nd Lieutenant C. A. A. Hawkins fought a hostile patrol at close quarters, and on the evening of November 22nd when the enemy attempted to raid an outpost of the Battalion. That outpost, commanded by Private H. C. White, put up a plucky fight, and after an eventful half-hour the enemy was beaten off with no greater loss to the defence than one man wounded.

Slight though the casualties were, that little fight was remarkable for the courage and resource displayed by Private White. When his Lewis-gun jammed and the enemy raiders were already struggling through the wire on three sides of the post, Private White ordered his party to evacuate, while he himself kept off the attackers by throwing bombs. Rejoining his party, he rectified the stoppage of the Lewis-gun, brought it again into action, poured fire on the enemy and then personally led the counter-attack, which chased the Bulgarians from the post. In this he was assisted by a Stokes mortar on the flank commanded by Corporal W. J. T. Ravenhill who, although his detachment was isolated, pluckily kept his gun in action (Cpl. Ravenhill and Pte. White both received the M.M.).

Early in December the 11th Worcestershire carried out a raid on two of the enemy outpost positions in front. Those two positions, known respectively as” Flat-Iron Hill” and” Diamond Hill,” were known to be occupied, but on those rugged hill sides it was not easy to estimate the enemy’s strength. A company was detailed to attack the former and half a company to the latter.

The raid, though carefully planned and well carried out, met with only partial success. On the left some Bulgarian patrols and outposts gave warning of the advancing company, and so heavy a fire was opened that the chance of surprise was lost. So the raiding company was first ordered to halt and then was withdrawn. On the right “Diamond Hill” was effectively rushed but there the enemy had fled. A fur coat and a steel helmet were among the trophies collected before the raiders withdrew (Total casualties of the two raiding parties were, 1 killed, 12 wounded.).

The Balkan winter had now set in, with mist and heavy rain. Both sides settled down into winter quarters, and the ensuing weeks, so far as the 11th Worcestershire were concerned, were marked by no outstanding incident.

The 11th Worcestershire were still regularly exchanging positions with the 7th Oxford & Bucks L.I. On December 19th the Battalion went into the front line, on that day an accidental explosion of a “dud “ enemy shell in a dugout caused serious the loss of 1 man who died of wounds, and 8 others wounded.

The Battalion remained in this area over Christmas Day— “a very happy and quiet Christmas Day. The enemy proving to be in sympathy by not shelling for two days.” On December 27th the Battalion moved back into a reserve position near Cidemli and there saw out the last days of 1917.

Note: This is an extract from the Worcestershire Regiment WW1 history by Captain H. FitzM. Stacke, M.C.