Brabant 1705

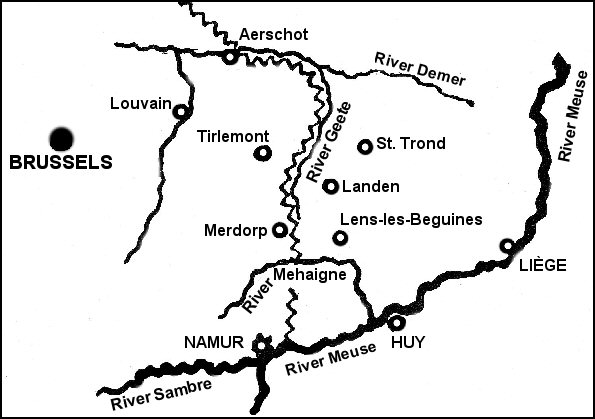

The main operations of the War of the Spanish Succession were in progress in Germany and Flanders. There, during four years of intermittent warfare, the allied Dutch and British forces had been withstanding the French invasion of the Low Countries. The first two campaigns—those of 1702 and 1703—had been inconclusive. During 1704 the greater part of the British forces had been diverted from Flanders to save from destruction our Austrian allies, then invaded by the combined forces of France and Bavaria. Those combined forces were shattered at the great battle of Blenheim, after which the Duke of Marlborough led his victorious army back down the Rhine to the Low Countries. The invading French armies had occupied the Belgic provinces of Flanders and Brabant, and had prepared against a possible counter-offensive by constructing great lines of entrenchments from Antwerp south-eastwards to Aerschot, and thence along the line of the Rivers Demer and Geete southwards to Namur. These lines—some sixty miles long in all—may appropriately be compared with the "Hindenburg Line" of the 1914-18 war. |

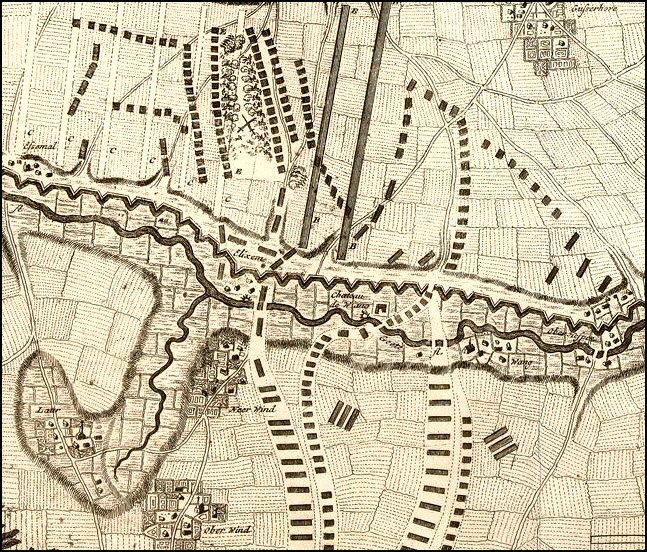

Brabant army lines 1705 |

For more than two years the Allies had not risked an attack on those entrenched lines (see Note 1), and behind them the French armies had lived in security and comfort. Now, encouraged by the victory of Blenheim, the Allied commanders planned to attack the French defences, and after capturing the outlying fortress of Huy (12th July 1705) they concentrated their forces opposite the lines. The Duke of Marlborough, commanding the British, and Veldt-Mareschal Overkirk commanding the Dutch forces, placed their headquarters at Lens-les-Beguines, over against the headquarters of the French Marshal de Villeroi at Merdorp. The two armies were approximately equal in numbers, and both were very composite as regards force, Marlborough squadrons, British, Dutch, North Germans, and Danes; while Villeroi could muster about 100 battalions and 146 squadrons, French, Bavarians, Spanish, and Walloons— total of about 70,000 men, but not enough to occupy the whole length of the entrenched lines. Consequently the bulk of the French forces was of necessity kept concentrated near the most probable point of attack with detachments guarding all the other possible points of danger.

First engagement of Farrington's Regiment (1st Battalion Worcestershire Regiment)

Sunset of Friday, July the 17th, 1705. In the headquarters of the great camp around Lens-les-Beguines the commanders of the Allied Army were in close consultation—the grim old Dutch Field-Marshal Overkirk, General Schlangenburgh and the Count of East Frisia, the Flemish Count of Noyelles, the Prince of Hesse-Cassel, the German Generals Salisch and Scholtz, the Duke of Wurtemberg, the Scots Lord Orkney, the Earl of Albemarle (see Note 2), and, dominating them all with his strong personality and unvarying charm of manner, John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough.

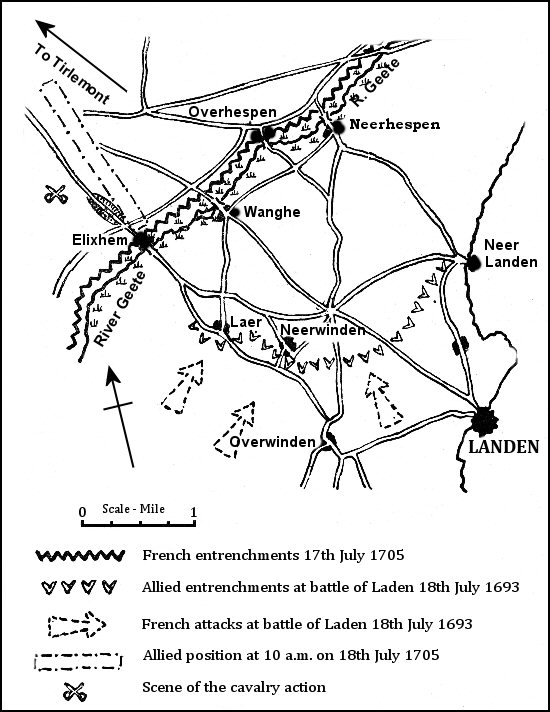

" . . . . . . . . . And so, your Highnesses," he was concluding, "our plans are fairly agreed. Our superiority in numbers is so slight that we cannot risk the heavy losses inevitable in a formal attack on the enemy's army in their strong entrenchments. Our only hope of success lies in outwitting our adversaries. We know that the main force of the enemy is concentrated in face of us around Merdorp. It is as obvious to them as it is to us that here, in the short stretch of open country between the Rivers Geete and Mehaigne is the ground most favourable for our attack. To the south of this gap between the rivers lies the strong fortress of Namur. To the northward the French lines are protected by the River Geete, marshy and unfordable, as too many of our soldiers found twelve years ago on the bitter day of Neerwinden. Every bridge across that river is guarded by a French detachment, but the enemy have the disadvantage of all invaders—they are in hostile country, and the country folk have given us information which our agents have fully confirmed. This information is to the effect that near Landen, ten miles north of our present camp, the narrow bridges at Elixhem, Wanghe, and Neerhespen those very bridges which saw the worst, slaughter after the battle at Neerwinden are only lightly guarded by small posts. |

Flanders overview map |

At Orsmael, two miles further north, there are indeed three regiments of dragoons, while the troops of Marshal de Villeroi's left wing—some thirty three squadrons at Gossoncourt and eleven battalions at Racour lie some four miles to the southward of Wanghe. That distance means two hours at least for the foot, even if the horse can come up earlier. The ground behind Wanghe is open, as we know, and very suitable for the rapid deployment of our forces. If we can once win the crossings at Wanghe and Neerhespen and can then form line of battle with sufficient speed, we may well beat our enemies in detail as they come up."

"But all depends, naturally, on the surprise of the bridges. With that object in view we have kept the most absolute secrecy as to our intentions, and during the last week I have allowed no movement or even reconnaissance, except by night, to the northward of our camp. On the other hand our forces have made many forays and demonstrations to the southward. I believe that our action has had the desired effect. This morning I have been informed that all four battalions of the Regiment du Roi, which has just arrived from the Moselle, have been sent to the extreme right of the enemy's line, together with three regiments of dragoons from their reserve. So little do the detachments near Wanghe anticipate danger, and so careless are they in their guard, that for three days and nights no patrol has come this side of the river."

"Our plans have now been completed for an immediate attack. This morning, as you know, the Dutch forces of His Excellency the Veldt-Mareschal have marched south six miles in full view of the enemy, as if in preparation for an attack near Merdorp, while some of my own troops have moved as if to support them and have made a great show of preparing bridges to throw across the Geete. At the same time I have arranged for certain letters to be captured which I hope Marshal de Villeroi is reading at this very moment—letters from my headquarters to the States General (The Dutch Government),

explaining my future movements, that in view of the poor forage here I intend to detach a portion of my forces to the northward, ostensibly to threaten the lines, but actually to occupy a fresh foraging area at St. Trond. Knowing our friend the French Marshal and the pleasure he takes in subsisting at his ease on a pleasant country-side (see Note 3), we think that he will credit a movement so much after his own heart—a quiet promenade to a safe area where the surrounding country would afford good subsistence to an idle army."

"After dark this evening at 8.0 o'clock, our army will assemble. At 9.0 o'clock the march will be led off by an advanced guard of twenty battalions and thirty-eight squadrons under General the Comte de Noyelles and General Scholtz. This detachment will force the passage of the lines at Neerhespen, Wanghe, and Elixhem. The rest of my army will march at 10.0 o'clock, and at 11.0 o'clock the Dutch forces of the Veldt-Mareschal will turn about, leave their present positions and follow our line of march."

"And now, your Highnesses, for the detail of our forces .................. "

Darkness fell that evening amid a bustle of preparation. Tents were struck, wagons loaded up, arms and ammunition inspected. Along the bivouac lines hundreds of camp fires were still blazing, camp fires which were to be heaped with fuel and left burning all night to deceive the enemy. Around one of these fires were grouped the senior officers of Farrington's Regiment (later became 1st Battalion The Worcestershire Regiment. The Regiment had joined the army in Flanders in June, 1704, but had not as yet been present at any large engagement.).

"So we're to march northwards," said Major Christopher Wray (see Note 4), "That will bring us near your old battlefield, Colonel."

"Aye," answered Colonel Watkins (see Note 5). "We're near enough—ten miles at most. I wonder how the ground looks after all these years. I never saw it after the battle (see Note 6) myself, for I was wounded the next year and invalided home; afterwards, when I was promoted into the First Guards, I was with their 2nd Battalion, which was kept at home for fear of invasion until '97, and that last campaign was fought further west, around Brussels. I wonder if they've rebuilt any of the cottages I saw go up in flames that day at Neerwinden."

"A desperate fight your Coldstreamers made there," joined in a tall Captain, Charles Cratchrode (see Note 7). "I was aide-de-camp to Brigadier Ramsay that day and, as you well know, Colonel, our Brigade held the right flank at Laer, where the fighting was hot enough. Twice we were beaten out of the village, and twice regained it. After Angus's Cameronians (see Note 8) and Churchill's Buffs (see Note 9) had fought their way in a second time through the ruins, my Brigadier sent me over to see how your Foot Guards were faring at Neerwinden, and I reached your entrenchment just at the same moment as the French cavalry broke through the smoke of the burning houses of Neerwinden village. 'Had to ride right through them, and 'twas sheer luck I reached your men at the cross-roads behind the village. I'll never forget how your Guardsmen fought, beating back the French infantry on both flanks—and when the red coats of those damned Irishmen of King James (see Note 10) came pressing through the smoke your men sang Lillabulero into their faces between each volley."

"Yes, that drove them wild; but we held them well enough, and when the Maison du Roi' (The French Household Cavalry) came charging in on us from the other flank we faced about our flank companies and shot 'em down, Some of them crashed right into us as they fell, and a private of my Company secured one of their standards, to our great jubilation. But what became of you then, Cratchrode?"

"I stayed with your Coldstreamers until King William himself ordered the retreat. Then I felt that I had to ride back, and by the grace of God I won through again to my Brigade. But by the time I reached Brigadier Ramsay the Scots Brigade had been beaten out of Laer again, and we had to fight our way back as best we could through all the French cavalry. God, that was a butchery! We made first for the bridge at Wanghe, but the French horse were there before us, slaughtering a great crowd of broken Brandenburgers. So the remnant of us fought our way out to the right and pushed on through the rout to Neerhespen. We had hard fighting all the way, for their horse and dragoons charged in again and again, intent to capture the Colours of the Buffs, and only about two hundred of us still held together by the Brigadier. But when at last we got to Neerhespen, we found some of your Foot Guards, still in good order, with King William himself holding the bridge. And I remember how your men beat back the pursuit at the bridgehead while we filed through to safety.

The Lines of Brabant 1705 |

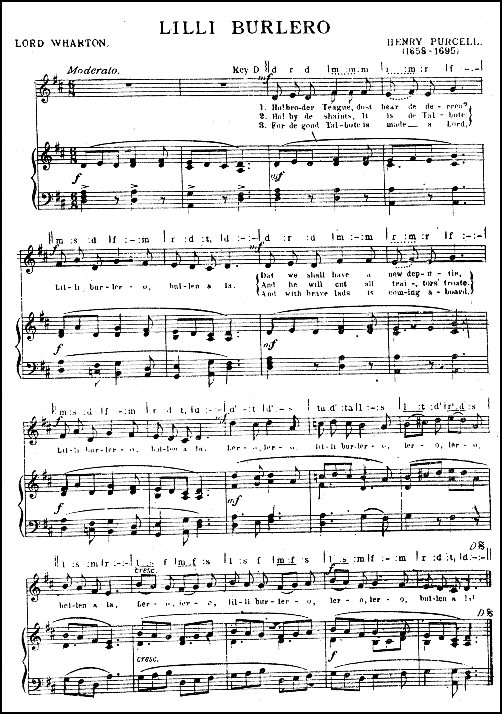

"That bridge at Neerhespen! Yes, I've good reason to remember it," answered the Colonel. "Two long miles we had to retreat before we reached it, through such a rout as pray God I'll never see again. But my Coldstreamers never broke, and we beat off both foot and horse till we got to the bridge. There the King called us to stand and hold the passage for the rest to escape. So we stood. By that time the French horse had it all their own way, and were cutting down the Germans like sheep, driving 'em into the marshes all along the river, while such as could reach the bridge were crowding over it in panic. But my men never lost heart — faced about with a will and even started to sing again after they'd beaten off one or two disordered attacks. Strange how our men will always cheer up and sing their best when things are at their worst! Somebody started Lillabulero again, and my poor devils, after five hours of the savagest battle ever seen, still shouted and whistled that damned old tune and held that bridge till the last of the fugitives were across." "Odd how that song has held its own," mused the Major. "Sixteen years now since it drummed James Stuart off the throne. I've heard the whole battalion of Kirke's Lambs (see Note 11) whistling it as we waded and fought our way across the Boyne, and Lord Cutts' forlorn hope (see Note 12) singing it as they went up the breach at Namur. Even now you hear it at times—some old sweat (see Note 13) starts it and the young lads take it up. In truth it has never been replaced. There's no new song nowadays which is so well known ." (see Note 14) "What gave it that success," asked the Adjutant (see Note 15); "Not the old words, surely, for they're silly enough." "Aye, but they met the spirit of the time. Anything Irish then would rouse the troops to scorn, and the mock Irish words of the verse went down splendidly—and that chorus . . . . . . . . . . exactly the sort of gibberish one used to hear all those years we fought up and down that cursed country. Even if the Irish didn't exactly say Lillabulero their idiotic language has other words just like it ; and anyway it's a wondrous chant if you once get it going—'Lero, Lero, Lillabulero . . . . . ' " |

"Nevertheless, sir," said a young ensign from the other side of the camp fire, "I do much prefer the words they're singing to it in London now.

"Aha, the last from home—and what were they singing to it in Vauxhall when you left, young William (see Note 16)"

"Surely you know the latest words, Sir. They're all over Town." The boy laughed a little, as at a pleasant memory, and then hummed:

"The ladies at Court so fickle are grown

That a true heart can hardly be met.

Love is for interest only a loan,

Which when 'tis spent they quickly forget.

'Tis true, you'll find some darlings so kind . . . . . . "

(he broke off, whistled a line between this teeth, then hummed again)

"With sorrowful ditty they clai-aim your pity

But pay for it only by cent-per-cent." (see Note 17)

"Sentimentalist," chaffed the Major. " No, sir, a convinced cynic

And at that moment the drums sounded (see Note 18) for the battalion to fall in.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Through the night the long marching columns tramped northwards along a rough road, the men stumbling in the mist among the ruts cut by the gun wheels and cursing beneath their breath, for absolute silence had been strictly enjoined. Mile after mile they marched, checked at intervals, as in every night march, by blocks in front. None of the regimental officers or men knew their mission, but many of them recognised the path they trod.

"The very road," whispered Colonel Watkins to his Adjutant, as they rode on the grass beside the marching column. "The very road up which that hunch-backed devil Luxembourg drove on his battalions to attack us. These ruins must be Overwinden. Landen should lie to our right and Neerwinden straight in front."

"How far, Sir?" "About half a mile—half a mile to the bloodiest field that the last century ever saw. Twenty thousand soldiers are sleeping here, Lewis ! 'S'death!" His drowsing horse stumbled and snorted as its hoof struck ringing against something white which crunched softly in the darkness. "What's amiss, Sir?" "Some poor devil's bones. We're on the battlefield."

The mist thickened as they neared the River Geete, and the column tramped on past the overgrown ruins of old entrenchments to the cross roads beyond Neerwinden—the cross roads where twelve years before the Foot Guards had made their famous defence. Then word was passed to halt, and the troops dropped off to sleep in their ranks, right in the centre of the old battleground. "It would seem, Sir," whispered the Adjutant, "that the Duke has planned for you a wondrous revenge."

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

A mounted aide-de-camp rode along the column, giving a message in low tones; the troops stumbled to their feet and fell in; the march was resumed northwards along the road. Checks from in front . . . more checks. Dimly through the mist the outlines of man and horse grew clearer in the first faint light of dawn. Then came another aide-de-camp galloping with an urgent message. In the mist many of the advanced troops under General Scholtz had gone too far to the left, and had taken the road to Overhespen by mistake. Webb's Brigade (see Note 19) were to hasten their march and support the attack on the bridge at Neerhespen.

The troops stepped out with a will. The light of dawn increased, and as Farrington's Regiment, at the head of Webb's Brigade, came in sight of the river valley, the mist faded away before the first beams of the rising sun, showing close at hand the little village of Neerhespen —a cluster of old ruins and new-built shacks—and, on the slope beyond the river, the enemy's entrenchments—big angled earthworks protected by a hedge of planted thorns and sharp stakes. In front, the leading troops of General Scholtz's advanced guard were crowding down towards the bridge. From a barricade in the ruined village puff after puff of smoke shot out, followed by the sharp "bang" of muskets in the still air of dawn. On the earthworks beyond, heads appeared—heads with the round furred caps of French dragoons. "If they've pluck enough, they can hold that bridge yet," growled Colonel Watkins. "Just as my Coldstreamers held it twelve years ago; and there are not enough of Scholtz's men to force it if they stand. Pray God those in front rush for it. Drum Major, play your damnedest, so that they'll know we're close behind 'em." "The old tune, Sir?" "Aye, the old tune—let 'em have it." With a crash the drums (see Note 20) broke out, and a rippling cheer ran down the column at the sound of the old lilting tune. Somewhere in the ranks a hoarse voice rose, chanting in fierce mockery of an Irish brogue. "Dere wuz an old prophisy found in a bog . . . a dozen voices answered: The note rose higher: With a roar the whole column gave tongue in the rollicking lilting chorus— "Leero-leero-Lillabuleero— |

Lillabulero song |

In front of them the French muskets were banging fitfully along the parapets, but already Scholtz's men were charging through the village to gain the bridge. For one moment the issue hung in the balance; then the sight of the massed red-coated battalions pouring down the slopes drumming and singing proved too much for the thirty or forty French dragoons at the bridge. Abandoning their barricades, they hurried back and disappeared behind the entrench¬ments. With fierce cheering, Scholtz's men rushed the bridge and could be seen for an instant silhouetted on the sky-line as they crowned the entrenchment beyond. Behind them Farrington's regiment and the others of Webb's Brigade marched in triumph over the bridge, across the river, and through the captured entrenchments. "Indeed," laughed Colonel Watkin, "this is a pleasant revenge. Those Frenchmen made no fight at all at this bridge which we once held against them for hours. Why in God's name have they let us in like this?"

Beyond the captured entrenchments the battalion came to a halt on the rising ground west of the Geete. Looking southwards in the morning light, the troops could see that the enemy's entrenchments had likewise been rushed at other points. Half a mile away at Overhespen, beyond that again at Wanghe, further again at Elixhem, battalions of Allied troops could be seen forming up on the open ground behind the lines. At each crossing place the weak outpost of dragoons had fled before the assault. East of the river the open ground showed long columns of the Allied troops tramping down to the captured bridges. Squadron after squadron of English horse came trotting up to Neerhespen and passed clattering and jingling over the bridge, afterwards deploying into a line facing south-west to cover the captured area against counter-attack by the enemy's cavalry until the whole army should be across the river and ready for battle. After a short halt Webb's Brigade marched forward again to the higher ground between Wanghe and Tirlemont, and there formed up in rear of the halted cavalry (see Note 21). Battalion after battalion of the Allied army marched into the captured position and formed in readiness for battle in a long line stretching from Elixhem north-westward over the rising ground to where the towers and steeples of Tirlemont rose above the horizon.

Presently a low murmur ran along the halted ranks. "They're coming," and in the distance to the southward could be seen squadron after squadron of the enemy cantering up to the danger point over open rolling ground, their swords and cuirasses sparkling in the rising sun. Nearer they came and nearer, till the watching eyes could discern the colour of their uniforms—the light blue of the Bavarian Life Guards, the yellow of the Spaniards, the pale grey or dark blue of the French Cavalry, as regiment after regiment wheeled into line to face the red-coated squadrons of England. Behind them came trotting batteries of artillery, and further off the approach of battalions of the enemy infantry could be foretold by the low clouds of dust. The hostile cavalry formed line opposite the British position but half a mile away, and for a time made no effort to attack.

From Elixhem on the left of the Allies' new position came the rattle of musketry followed by rapid reports of artillery, as the enemy's field guns unlimbered and came into action. There the Allied infantry had secured a position in the hollow road which runs from Elixhem to Tirlemont, and were engaging the enemy's leading troops. Suddenly along the whole line of the waiting British cavalry trumpets rang out. The Duke of Marlborough himself had taken command and had decided to attack the enemy's cavalry before their infantry could back them up.

As the long line of red-coated horsemen trotted forward across the open ground, the enemy's squadrons also started into movement, glittering with steel and silver as they moved. The British cavalry trotted down into and up out of the hollow road, and then, quickening their pace, rode straight at the enemy. The two long lines of cavalry met with a shock, and in an instant the hostile array was broken by the fierce thrust of the British cavalry. One English regiment, Cadogan's Horse (see Note 22), crashed into the light blue Life Guards of Bavaria and drove them in headlong rout, capturing their four squadron standards. Further to the right the Scots Greys overthrew the Spanish cavalry. In a few minutes the enemy's squadrons had dissolved into a mob of fugitives galloping wildly out of the fight, while behind them the ground was strewn with struggling horses and fallen men (see Note 23).

On the left flank the victorious British squadrons wheeled outwards and took in flank the French field batteries, riding through the guns and cutting down the gunners as they ran (see Note 24). Then, with much shrilling of trumpets and wheeling of scattered horsemen, the red-coated cavalry began to re-assemble and re-form.

But five fresh squadrons of French cavalry came galloping up, and behind them some rallied Bavarians and Spaniards rode in again for a second fight. Charging headlong at the disordered redcoats, the French horsemen crashed into an English squadron close by the Duke of Marlborough himself, and a desperate melee surged all round the British leader. A Bavarian officer hewed at the Duke with a stroke so wild that he lost his balance and fell from his horse at the Duke's feet, whence he was picked up as a prisoner by the British General's trumpeter. But in a few moments that second attack was broken like the first, and the enemy horsemen were driven back in rout on to their own infantry.

Ten infantry battalions of the enemy had now reached the scene of action. On seeing the wild melee of horsemen to their front, their commander, the Count de Caraman, prudently halted and formed his battalions into a great hollow square. Their routed horsemen galloped back past their flanks and actually between their companies, but the well drilled battalions kept their heads and maintained good order (see Note 25). For a while they stood their ground, while the British cavalry again rallied and re-formed, but no support was in sight (see Note 26), and the Allied infantry in their front were overwhelming in numbers—numbers which were increasing every minute as fresh battalions tramped up across the Geete and through the captured lines.

Soon the Count de Caraman decided to retreat on to the main body of his army, and he withdrew his ten battalions, still in their hollow square formation, across the open country towards the south. The British squadrons followed the retreating battalions and hung on their flanks, chafing for permission to ride home and rout the foot even as they had routed the enemy's horse. But the great Duke was too wary to throw away his splendid cavalry in charging unbroken infantry across open ground. He forbade any further attack, and presently the retreating enemy passed out of sight.

By that time the leading battalions of Overkirk's Dutch brigades were joining Marlborough's men at Elixhem and Wanghe. The whole Allied army was concentrated in superior numbers on the enemy's flank behind the defences upon which the French had relied, and no good course was open to Marshal de Villeroi but rapid and ignominious retreat. It would have been possible for the Allies to strike in against the flank of the retreating French army, but the Duke did not hold an undivided command. The other Allied generals wished to take no risks, and all the Allied troops needed rest and food after their hard night's work. So the army stood fast on the ground gained, reckoning the prisoners and trophies of the fight (see Note 27), while tents went up and pioneers set to work to demolish captured entrenchments. Far away to the south, long columns dust marked the disorderly retreat of the French westward to their next possible line of defence—the River Dyle about Louvain.

In the exultation of their success, the troops did not guess that delay would lose them the chance of a decisive victory for many a long month to come. Their great commander realised it and urged the Dutch to march. But prejudice and jealousy were ranged against him, and he had to be content with what had been achieved. With trifling loss he had driven the enemy from their secure position of the last three years; his able plans had been carried out to the letter, and he had seen his cavalry rout equal numbers of the enemy in a fair fight. With all confidence he could reckon on greater victories to come.

So we may leave him for the present, explaining with his infinite courtesy that the success has really been due to the loyal co-operation of all his brave allies, while company by company his men file off to their bivouac lines, whistling merrily their ribald old tune—

"Lillabule-ero, Lillabule-ero, . . . . . . . . . . . . "

Note:

1. The entrenchments of those days consisted of high and solid breastworks of earth, revetted by gabions and fascines and covered by a hedge of thorns and sharp stakes (in place of the barbed wire of to-day). Against such defences the small smooth-bore field artillery of the period, firing solid cannon-balls, were of little effect and Overkirk having some 75,000 men, forming 92 battalions and 160

2. Who, despite his British title, was a Dutchman, brought into the British service by King William III.

3. At that period the approved method of making war was to occupy the enemy's territory and to subsist on it until the enemy sued for peace. Consequently operations were very dilatory, the object of a skilful invading general being to delay and avoid any costly action. Campaigning in the XVIIIth Century was often very much of a picnic, especially in the French armies, which were noted for their slack discipline and were always encumbered by much impedimenta, including very many ladies. Our term "marquee" for a big tent is a reminder of the luxury with which the French noblemen took the field.

4. Second-in-command of Farrington's Regiment from its formation in 1694 until promoted to Command in 1707.

5. Colonel William Watkins, originally (1691-95) in the Coldstream Guards. Promoted into the First Guards (now The Grenadiers) in 1695. Exchanged to command Farrington's Regiment in 1702.

6. The battle of Landen or Neerwinden, 18th July, 1693, in which the allied Dutch British, and North German army under King William III was completely defeated, after a heroic struggle against odds, by the French army under Marshal Luxembourg. King William committed the tactical error of fighting a defensive battle with an unfordable river (the Geete—see plan) at his back, with the result that when forced back from their entrenchments large numbers of his troops were unable to escape, and the battle ended with a wholesale massacre of the fugitives. The Allied casualties were reckoned at about 12,000 out of a total of about 50,000 engaged.

7. Afterwards Major (1707) and Lt.-Colonel (1710-17).

8. Later became known as the 1st Battalion of The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles).

9. Later became known as The Buffs (East Kent Regiment).

10. The Irish Brigade in the French service, who considered themselves the Stuart Royal Army and always wore the British red uniforms.

11. Later became known as the Queen's Regiment.

12. The contemporary term for a body of volunteers picked for any desperate enterprise such as the storming of the breach of a fortress. The victorious attack at Namur was led by Lord Cutts, nicknamed "The Salamander" from his reckless love of the hottest places.

13. The expression occurs constantly in contemporary broadsheets.

14. "Lillabulero" leapt into fame as a political chant at the Revolution in 1688. Consequently in 1705 it was about as old as "Tipperary" is to-day. But in those days there was not the constant output of new tunes that submerges every temporary success to-day, and the continued popularity of the old song is evidenced passim in "Tristram Shandy."

15. Lieut Francis Lewis, first commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant of the Grenadier Company of Farrington's Regiment in 1694.

16. Ensign William Carr, commissioned in 1702, but apparently did not reach Flanders till the spring of 1705.

17. This is possibly an anachronism. These words are (practically) those which were sung to the famous old tune (with a whistling chorus) in the " Beggars Opera" twenty years later. But these words may well be older than Gay's immortal work. In any case there were many versions of "Lillabulero," for it is the sort of tune to which it is easy to put new words.

18. Bugles were not introduced until the Nineteenth Century in English Line regiments.

19. Webb's Brigade consisted of the following Regiments — Farrington's, Tatton's (later known as the South Wales Borderers), Ingoldsby's (later known as the Royal Irish Regi. ment), and Temple's, (subsequently disbanded).

20. Fifes had not then been introduced. Cymbals and hautbois sometimes accompanied the drums, but of ten the troops sang in chorus on the line of march. When companies marched independently each was headed by its own drummer, who beat time while the troops sang what they pleased. Each company then had its own Company Colour carried by the Ensign of the Company (Battalion Colours were not introduced until later), and the head of a Company on the march must have been as shown (in silhouette) in the tail-piece to this article.

21. Webb's Brigade was then on the extreme right flank of the new Allied line, which stretched from near Elixhem to half-way to Tirlemont.

22. Later became known as the 5th Dragoon Guards.

23. This charge of about thirty squadrons on each side:was one of the most spectacular in the whole history of the British Cavalry.

24. The captured French guns proved to be of novel design, with three barrels to each gun, giving great rapidity of fire. They were sent home to be copied in England; but somehow they never got copied, and the unique design seems to have been lost.

25. Parker says the ten battalions were Bavarians, but Taylor states that the bulk of them were Alsatians and Spaniards.

26. Apparently the intercommunication of the French army was so faulty that no clear message as to the situation reached Marshal de Villeroi until 10.0 a.m.

27. Prisoners, about 1000, including 79 officers, among whom were five Generals of Cavalry, notably the Marquis d'Alegre and the Count de Horn. Also 10 guns and nine cavalry standards. British casualties about 200.