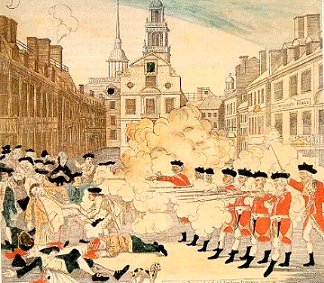

The Boston Massacre 1770

In 1765, almost without debate and scarcely a thought that it might be resented, the Stamp Act was passed by the English Parliament. The tax, intended to help cover the cost of stationing troops in America, was justified as it was deemed only right that the colonists should bear their share. The colonists’ resentment was not against the raising of revenue but against the principle of taxation without consent. Opposition was determined. Groups were formed calling themselves ‘The Sons of Liberty’ and English goods were boycotted. This proved effective, for the London merchants resented the loss of trade and in the spring of 1766 the act was repealed.

Nevertheless, Townshend, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, availed himself of any chance to impose further restrictive measures. One that caused particular anger was the establishment of a Board of Commissioners in Boston to collect taxes. The situation in Boston now deteriorated to such an extent that two regiments were ordered from Halifax to the city—these were the 14th and 29th Foot.

From now on much of the venom the colonists felt towards the home government was directed against the soldiers, representatives of all that they so heartily hated. As winter drew on tensions grew and tempers became stretched as hostility to anything English mounted. The soldiers were tormented by the citizenry and the provocation to retaliate became almost unbearable. ‘Bloody backs, lobsters for sale, who will buy?’ cried the urchins. All the men could do was to spit and curse. A famous Boston citizen was even constrained to rebuke a boy he saw throwing ice at a sentry.

One day three soldiers of the 29th when strolling in Gray’s Ropewalk were accosted in an outwardly friendly manner and, as was not uncommon, asked if they wanted work; on their reply that they would, an uproar ensued. The incident had been staged to trap the men. Nobody was hurt, however, and the crowd dispersed; but the next morning the following poster appeared:

This is to inform the rebellious people in Boston that the soldiers of the 14th and 29th Regiments are determined to join together and defend themselves against all who shall oppose them.

No one could be sure who posted the notice but there was more than a suspicion that it had not been the soldiers. Someone was trying to provoke an incident. Tension now reached boiling point and the explosion came on 5th March.

The snow was falling and parties of youths were hanging about the street corners while groups of soldiers out for a stroll had armed themselves with cutlasses. By evening crowds had grown, most of whom carried sticks and cudgels. During the late afternoon a Captain Goldfinch on his way to barracks was taunted by Edward Garrick, a wig-maker's apprentice, who shouted that Goldfinch had not paid his master (the barber). Hugh White, who was on duty as sentry at the Custom House, King Street, drove the boy away shoving him with the butt-end of his musket, knocking him to the the ground. The boy set up a howl and a crowd quickly collected pelting the sentry with snow and ice. Captain Goldfinch ordered his men inside and shut the gate, at the same time promising the people that no soldier would be let out that night.

The peace of the night was disturbed when someone pushed a small boy through the window of a church in the north end of the town, with instructions to toll the bell as for fire. Crowds turned out, but eventually all was quietened down and the lone sentry once again paced before the Custom House. At 2100 hours a man was heard addressing a growing mob. This mysterious figure, said to be grey haired and wearing a red cloak and who figured largely in the subsequent trial, was in fact never identified. His impromptu diatribe, however, started the onlookers towards the sentry and the guard at the Custom House. A second group, moving from Royal Exchange Lane, converged on the same spot and someone shouted, ‘Here is the soldier that struck the barber’s boy.’ The mob started yelling, ‘Kill the soldier, kill the damned coward, kill him, knock him down!’ The sentry was forced to back up the steps and, under a hail of chunks of wood and great lumps of ice, now primed his musket. Taunted because he dare not fire, calling him a coward and foully insulting him, they even attempted to drag him into the street. At this he called to the guard for assistance.

The guard was commanded by a young inexperienced officer, Lieutenant Bassett. The Captain of the Day, Captain Thomas Preston, realizing Bassett’s youth, came along to see what was happening. Preston could see that the mob was getting out of hand and, realizing that in the Custom House was lodged a considerable sum of government money, he hastened to the guard which he found already under arms. He deployed the guard and then proceeded with a corporal and six men, one of which was Private Hugh Montgomery, to protect the sentry, Hugh White, (as well as the chest containing the money). As Preston drew close he found the mob, now increased to about 100, in an ugly mood. They were whooping, whistling between their fingers, and hurling anything that came to hand— clubs, oyster shells, and snowballs—at the sentry.

Sam Gray, who had caused the commotion at the Ropewalk on the previous Friday, was much in evidence. A mulatto of herculean size, called Crispin Attucks was crying, ‘Let us strike at the root; let us fall on the nest! The Main Guard, the Main Guard!’ The soldiers coolly loaded their firelocks and fixed bayonets, while the mob, unintimidated, closed in on them. The mob beat at the bayonets and muskets with clubs, shouting, ‘Knock ‘em over; kill ‘em!’ The mulatto aimed a blow at Preston which though it only fell on his arm knocked over a musket, the bayonet of which the mulatto now seized. At the same moment there was a confused shout from behind the captain,’ Why don’t you fire?’ Private Montgomery, whose rifle bayonet had been grabbed by Attucks, and who had fallen down, rose to his feet once again in possession of his musket and fired. Attucks fell dead. Five or six more shots were fired. Three persons were killed and five wounded, some only slightly. The mob instantly retreated, leaving their dead and wounded on the ground although they soon returned to carry them off.

Trial testimony never definitively answered the question of who shouted "fire" and who fired the fatal shots. In 1949, however, with the long-delayed publication of notes of Thomas Hutchinson, it was revealed that Montgomery admitted to his lawyers that it was he who started the Boston Massacre. Hit in the chest and knocked to the ground by a club wielded by one of the rioters, Montgomery responded, he said, by shouting "Damn you, fire!" Montgomery fired first, then the other soldiers followed. The soldiers, supposing that another assault was to be made, prepared to fire again. Preston prevented this by striking up their weapons with his hand. He was then told by one of the townsmen that a crowd of four to five thousand had collected and sworn to take his life and those of all his soldiers. Judging his position unsafe Preston withdrew with his men to the main guard where the Street was both narrow and short. He placed a party at each end of the street. He ordered his drums to beat to arms and soon was joined by several companies of the 29th. The 14th were also under arms but remained in barracks. Preston sent a party under a sergeant to Colonel Dalrymple, commanding the 14th, to apprise him of the situation. Several of the officers of the 14th going to join their regiment were knocked down and one was seriously wounded having his sword taken from him. Soon after the Governor and Colonel Dalrymple met and, deciding that the regiment should return to barracks, ordered the people to return to their houses. |

Boston Massacre of 1770 by Paul Revene |

The following morning Preston and Bassett were imprisoned and in the forenoon the eight soldiers were also arrested. There followed a trial as important as has ever been heard in a British Court. Politics, emotions and justice were all in conflict. Politics or the lack of political wisdom had produced an emotional situation for which soldiers had to pay the price. Politically it was necessary to prosecute them as only by a fair trial could the authorities be sure of preventing the mob from lynching the defendants. Here was a dilemma. How could the Crown think of hanging British soldiers who in the face of great provocation had fired on an unruly, treasonable and dangerous mob? Justice was in conflict with emotion, for emotion demanded the finding of ‘guilty’ whereas justice called for a fair trial. That Preston and his men had a fair trial was due to one man only, John Adams.

As arrangements for the trial started, the people demanded the removal of the two regiments. At first the Governor agreed only to the 29th going, but later he was forced to agree that both should leave and on 27th March His Majesty’s 14th and 29th Foot marched out of Boston in the most humiliating circumstances. As they marched to the wharf they were escorted by the ‘Sons of Liberty’, as jubilant as the troops were glum. Side by side with the regimental commanding officer marched the captain of the ‘Sons’, who wore a red and blue uniform left over from the last Pope’s Day parade; he carried an old musket and wore a three-cornered hat at a jaunty angle in which was a gay cockade. As he bowed genially to the people they responded with roars of laughter. All Boston turned out and the windows were festooned with ladies in their finery, while small boys in hordes ran along the gutters. Never had His Majesty’s soldiers been so bitterly ridiculed and shamed. Discipline, and discipline alone, held these men together.

‘The Boston Massacre’ of 1770. It was for their part in this engagement that the Regiment was nicknamed ‘The Vein Openers’, although they were acquitted of all blame and even defended at the subsequent trials by the famous lawyer and revolutionary, John Adams.