Albuera (16th May 1811)

Sir John Fortescue, the great historian of the Army, has said that of all the battle-honours which a regiment can bear on its Colours, Albuera is one of the most to be envied, ranking in glory with Waterloo and with Minden alone. Those three battles, each in its own way, were the three supreme achievements of the British soldier in the old days of redcoats and muzzle-loading muskets.

Waterloo perhaps stands in a class by itself, for there the staunch defence of the British battalions ended in the greatest victory of all time, and settled the destinies of Europe. But Minden and Albuera, although both were minor battles strategically, and neither ended a war, nevertheless rank above all the other historic fights of our Army as examples of sheer bravery and of the prowess of British infantry. At Minden six British battalions, advancing unsupported in consequence of a mistaken order, attacked a French army of many times their strength, repulsed repeated charges of the finest cavalry in Europe, broke through the centre of the hostile line, and forced the enemy into heading retreat. With very good reason the six regiments who fought at Minden celebrate that day. But Albuera was an even sterner trial—a battle in which victory was plucked from the very jaws of disaster by the splendid fighting of the individual regiments— and its story is one which will be remembered as long as our Army lasts.

Strategical.—The Peninsular War had begun, so far as the British Army was concerned, in 1808. In the previous year Napoleon had occupied the greater part of Spain and Portugal with his armies, and had roused the Spanish people against him by forcibly deposing the Bourbon King of Spain and installing his own brother, Joseph Bonaparte on the throne in Madrid. To assist the Spaniards and Portuguese in their fight for freedom, a British Expeditionary Force was sent to the Peninsula, landing in August, 1808.

After three years of varying fortune, marked by the battles of Roleia, Vimiera, Corunna, Talavera, and Busaco, the British Army under Lord Wellington was forced back by superior numbers in the autumn of 1810, right back to the sea-coast near Lisbon. But there Wellington had prepared the fortified lines of Torres Vedras to protect the Portuguese capital, and in the safe shelter of those fortifications he stood at bay throughout the winter of 1810-11. When spring came on, Marshal Massena, the French commander, found himself obliged to retreat, since the devastated countryside could no longer support his army.

Meanwhile in Spain the whole country was seething with revolt against the French invader. Numerous bands of “guerilleros” were cutting up French detachments and interrupting the invaders’ communications, while some small Smanish armies were still in the field in the south-western provinces of Andalusia and Estramadura. Those remnants of the once proud army of Spain were in sad plight, and were repeatedly routed and dispersed by French detachments; but they re-assembled and renewed the struggle from time to time. A few Spanish cities, notably Tarragona, were yet unconquered; and the part of Cadiz, still in Spanish hands, and supplied by the British fleet, provided a centre of resistance.

After retreating from Portugal, Marshal Massena, with the main French Army, remained just outside the Spanish border about Salamanca, covering Madrid. At the same time a second French army, under Marshal Soult, which had been operating in the South of Spain, was occupying the country around Seville, and was endeavouring finally to subdue that part of the Peninsula. Lord Wellington himself, with the main Anglo-Portuguese Army, advanced north-eastward from Lisbon against Massena’s army—an advance which was to result in the seige of Almeida and the battle of Fuentes d’Onoro. At the same time he detached a force, under Sir William Beresford, to advance south-eastward towards Estramadura. The immediate objective of that force was the fortress of Badajoz on the frontier between Portugal and Spain. That fortress had recently been captured by the French, and its recovery was necessary to enable the Anglo-Portuguese forces to co-operate with the Spaniards in Estramadura. In the last week of March, 1811, Sir William Beresford’s force reached the neighbourhood of Badajoz, and, after a sharp little fight at Campo Mayor, surrounded the fortress and commenced to besiege it, digging trenches and erecting batteries to bombard the walls. The siege was not very successfully conducted, and dragged on with little result, while 200 miles away, at Seville, Marshal Soult collected his forces to march to the relief. Soult’s arrangements were hampered by the need for leaving strong garrisons at several points to hold down the hostile population of Andalusia, but he could assemble a field army of about 25,000 fighting troops. |

Lieut.-General Sir William Beresford |

According to the information at his disposal, Beresford’s force was of about the same strength; but of the latter a large proportion were Portuguese, and the French Marshal reckoned that in fighting qualities his French veterans were worth more than equal numbers of their opponents. On May 9th he marched out from Seville, north-westward along the road to Badajoz.

Marshal Nicolas-Jean de dieu Soult |

Actually the forces of the Allies were greater than Marshal Soult had supposed, for the small Spanish Armies in the south-western provinces had been collected and re-organised into a force some 12,000 strong, which moved northwards from the neighbourhood of Cadiz to join Beresford’s army. This Spanish contingent was under the command of a General Joachim Blake, a Spanish officer of Irish extraction, a brave man but proud and difficult to work with. The British commander, Sir William Beresford, likewise an Irishman, was a fine fighting soldier, who had done admirable work in re-organising the Portuguese Army, to which he had been lent. Under his care, and with many British regimental officers commanding their brigades and battalions, the Portuguese had become fine fighting soldiers, who could be trusted to stand side by side with the British troops; and Sir William, a General in the British Army, held the honorary rank of Marshal in the Portuguese Army. A big man, of quick temper and high courage, he was nevertheless not a very clever tactician. On the other hand the French commander, Marshal Soult, was one of the most brilliant of Napoleon’s generals, and later was to prove a more successful opponent to the great Duke of Wellington than any other of the Marshals of France ; while the troops he led were superb. At that date the French Armies had been campaigning continuously for twenty years. Their eagles had been carried in triumph through nearly every capital city in Europe; they had driven Germans, Austrians, Russians, Italians, Dutch, and Spaniards in rout before them. Their officers and N.C.O.’s had all won their promotion by service in the field. A very large proportion of the rank-and-file were veteran old soldiers. A more formidable enemy it is hardly possible to imagine. |

Marching across the mountains of the Sierra Morena, Soult’s army came in touch with the Spanish and British cavalry patrols, which fell back, giving warning of his approach. As soon as the route of the French army was definitely ascertained, Beresford relinquished the actual siege operations, and, leaving a small part of his force to watch the fortress, moved south-eastwards from Badajoz to a selected position barring Soult’s line of advance, at the point where the main roads from Seville to Badajoz crosses the little river Albuera, at the village of that name. Blake’s Spanish force, moving up from the southward, was directed on the same point. On May 15th all three armies were in close proximity, although Soult did not yet know the strength of the Spanish contingent which was cooperating with Beresford’s English and Portuguese.

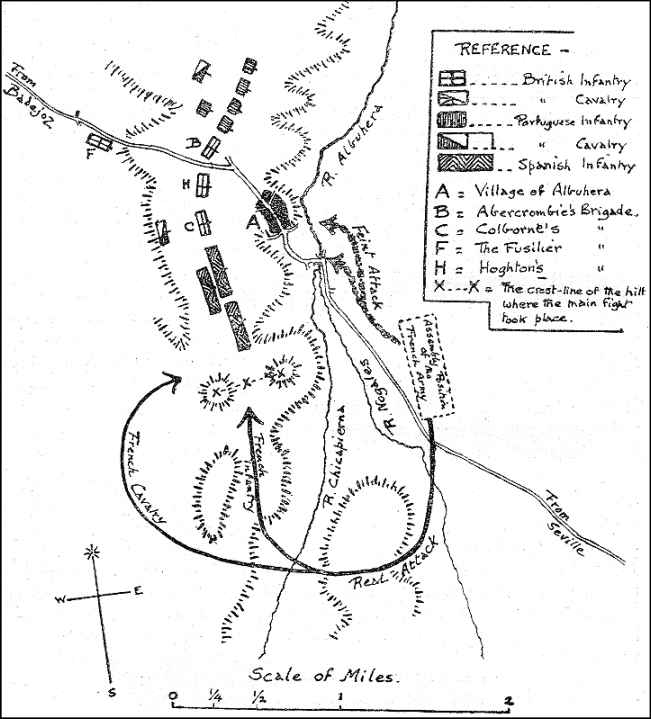

The Battle.—Early in the morning of May 16th, the French Army arrived before Beresford’s position at Albuera, and both sides deployed for battle. Beresford’s composite force consisted of about 9000 British (the 2nd and 4th Division of the British Army— 13 battalions, organised in 4 brigades, and 3 cavalry regiments), about 1000 Hanoverians (2 battalions of the King’s German Legion). 10,000 Portuguese (16 battalions and 8 squadrons), and 14,500 Spaniards, for Blake’s 12,000 had been joined by another small force under General Castanos—a total of some 35,000 of all arms.

This force was formed up along the low ridge which rises from the western bank of the little river Albuera—a stream which is formed from the junction, near Albuera village, of two tributaries, the Nogales and the Chicapierna. Albuera village itself was held by the two Hanoverian battalions 0f the King’s German Legion, with behind them the British 2nd Division—10 battalions in 3 brigades (see table below).

| Colborne’s Brigade | 3rd (Buffs), 31st (E. Surrey), 2/48th (Northants), 66th (R. Berkshire). |

| Hoghton’s Brigade | 29th (Worcestershire), 1/48th (Northants), 57th (Middlesex). |

| Abercombie’s Brigade | 28th (Gloucesters), 34th (Border), 39th (Dorsets). |

On the left flank of the British were the Portuguese and on their right the Spaniards. The latter had come into position under cover of darkness, and had blundered badly while taking up their ground, so that much readjustment was necessary in the early hours of the morning. Part of the British 4th Division had been left to mask Badajoz; the remainder — one infantry brigade of three battalions, which consisted of the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 7th Royal Fusiliers and the 1st Battalion of the 23rd Royal Welch Fusiliers, — was in reserve behind Beresford’s centre.

Battle of Albuera (16th May 1811)

The ridge upon which Beresford had taken up his position was bare and open, and was higher towards the south, rising into successive small hills each higher than that to its north, so that the position held by the Allies could be overlooked from the right flank. Five hundred yards to the south of the point selected by Beresford for his extreme right flank one of these rounded hills overlooked his line. He had not occupied this hill, both because it in turn was overlooked by another on its southern side, but also because such an extension would unduly weaken his defensive line. He anticipated that the French would attack directly up the main road through Albuera village, trusting in their fighting power and their moral superiority to carry all before them.

And, indeed, the opening phase of the battle seemed to justify that belief. On the eastern side of the Albuera stream the slopes were covered with low trees, so that the French movements were hard to discern; but presently French cavalry and infantry—three regiments of Hussars and Chasseurs-a-cheval followed by six battalions—advanced along the main road against Albuera and became hotly engaged with the two Hanoverian battalions which had been posted as garrison to the village. Other French troops demonstrated against the part of the position occupied by the Spanish brigades, south of the village.

But, meanwhile, under cover of the trees, Marshal Soult was massing his forces for a surprise attack against his opponents’ right flank. He had observed the unoccupied hill on Beresford’s right flank, had realised that thence he could outflank the whole line of the ridge, and had ordered the preliminary attack on Albuera village merely as a feint. When all was ready he suddenly launched his real attack. The main body of his army—I9 battalions of infantry— debouched from the shelter of the woods, and marched swiftly across the Nogalas and Chicapierna streams to gain the open hill. Ahead of them rode four regiments of light cavalry, and presently six more regiments of cavalry followed them at speed, passed the infantry and went on to cover the outer flank of the great wheeling attack.

As soon as this menace was realised, Beresford hastily directed Blake to form his Spanish brigades to the right and to occupy the empty hill. Blake made difficulties, and the movement was badly carried out. Nevertheless a brigade of Spanish infantry reached the hill and extended across the crest line facing south, just in time to meet the French onslaught.

The French attacked in a dense mass—a formation which had carried them to victory when opposed to other armies of poor morale—“to the Allies the whole 8400 looked like a vast column, with a front of 500 men only, which, allowing for battalion intervals, just stretched across the level top of the heights, which is here about 700 yards broad.” (Oman.)

To their eternal credit the Spanish battalions facing this formidable force stood their ground gallantly, while Beresford, realising too late what the loss of the hill would mean, ordered the three brigades of the British 2nd Division to march to their assistance. The leading British brigade—Colborne’s—came up on the right of the Spaniards and was just about to intervene effectually in the fight, when a sudden storm of rain burst over the battlefield. Masked by that rain the French cavalry, who had galloped out far round the flank of their attacking infantry, swung inwards and charged Colborne’s battalions in flank and rear. Caught entirely unprepared, three battalions—the Buffs, the 2/48th (Northamptonshire) and the 66th (R. Berkshire)—were almost entirely destroyed, the French horsemen capturing five out of their six Colours (one Colour of the Buffs was saved by Ensign Latham of that Regiment, who although mortally wounded, successfully defended his charge against the Polish Lancer who attacked him), and the savage Polish Lancers spearing the wounded on the ground. The fourth battalion of the brigade, the 31st (E. Surrey) formed square just in time, and beat off the horsemen, who swept on, driving many of the Spaniards before them. Sir William Beresford and his staff were attacked and had to fight for their lives; but the British General parried a lance-thrust, grappled with the lancer, and by sheer strength hurled him from his saddle to the ground. Through that wild melee the second British brigade—Hoghton’s—came up the hill, passed through the Spanish infantry on the crest and came face to face with the dense attacking mass of the French battalions. |

Polish Lancer |

“Then followed,” writes Sir John Fortescue, “a duel so stern and resolute that it has few parallels in the annals of war. The survivors who took part in it on the British side seem to have passed through it as if in a dream, conscious of nothing but of dense smoke, constant closing towards the centre, a slight tendency to advance, and an invincible resolution not to retire. The men stood like rocks, loading and firing into the mass in front of them, though frightfully punished not so much by the French bullets as by grapeshot from the French canon at very close range. The line dwindled and dwindled continually ; and the intervals between battalions grew wide as the men, who were still on their legs, edged in closer and closer to their Colours; but not one dreamed for a moment of anything but standing and fighting to the last. The fiercest of the stress fell upon Hoghton’s brigade, wherein it seems that every mounted officer fell. . . . Captains, lieutenants, and ensigns, sergeants and rank-and-file all fell equally fast. Nearly four-fifths of Hoghton’s brigade were down, and its front had shrunk to the level of that of the French; but still it remained unbeaten, advanced to within twenty yards of the enemy and fired unceasingly.”

It must be -explained that the British infantry of that period were trained to fight either in two ranks, as we stand to-day on parade, or else in three. The ranks fired together, the front rank kneeling while the others fired over their heads. Their weapon was a smoothbore muzzle-loading musket, throwing a bullet perhaps 200 yards, of which only the first 50 yards were tolerably accurate; and fire, to be effective at all, had to be delivered in volleys. The volleys were fired by platoons ; and the test of well-trained infantry was the number of volleys which could be got off in a given time. Apparently a really well-trained platoon could deliver about five volleys a minute. The principle of the fight was the same then as now—to obtain superiority of fire so as to break down the enemy’s morale and then to finish him off by the assault with the bayonet.

That desperate fire-fight lasted for perhaps half an hour; and the issue of the battle hung in the balance. The third British brigade of the 2nd Division—Abercombie’s—had been put into the fight on the left of Hoghton’s brigade, and some of the Spanish battalions were also fighting manfully; but other Spanish battalions wavered and would not come forward into the battle. Beresford’s only trustworthy reserve besides the Portugese was the one remaining British brigade—the Fusilier brigade, in rear of the centre of the line. In that moment of awful responsibility Beresford hesitated. Should he, or should he not, commit his last reserve? With it would go his last hope of effecting an orderly retreat if defeated.

Unknown to Beresford, his great opponent, Marshal Soult, was in a similar crisis of irresolution. Only when his attack struck the Spanish battalions had he learned that Blake’s army had joined Beresford’s, so that instead of equal numbers he had heavy odds against him. In view of this he hesitated to commit his last reserves to the attack, but waited to see how his main body fared before sending in the final reinforcements, which might have ensured victory.

And while the two commanders hesitated, the desperate fight went on upon the crest line of the hill, and still the last survivors of the 29th, the 48th, and the 57th barred the path of the French battalions, firing and firing into the dense mass which crowded up against them.

Colonel Inglis, of the 57th (Middlesex) fell mortally wounded; but in his last moments kept calling to his men to “die hard “—and his regiment has never forgotten that cry. But the 48th (Northampton) and the 29th (Worcestershire) sold their lives as dearly as their comrades of the 57th. Firing to the last, they went down one by one, until the battalion lines were broken into little groups.

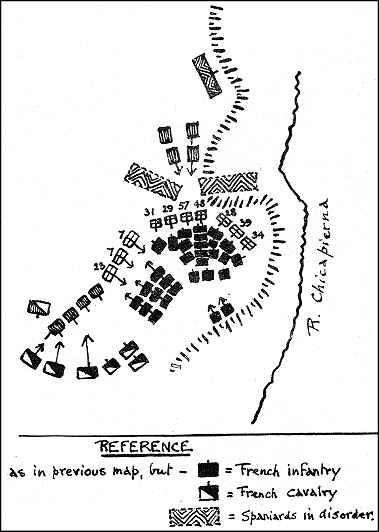

Situation at the Crisis of the Battle (about 11.15 a.m.) |

At that last moment a subordinate took the responsibility before which Beresford had qualied. On his own responsibility Colonel Hardinge, of Beresford’s staff, who had been sent with some message towards the reserve, rode to General Lowry Cole, under whose orders was the Fusilier Brigade, and urged him to advance. After a short consultation with General Lumley, who commanded the cavalry, Lowry Cole ordered the Fusilier Brigade to move forward, together with a brigade of Portuguese. The two brigades advanced in line, the Portuguese covering the right flank of the British Brigade from attacks by the French Cavalry, whom they repulsed with great steadiness; while the three British Fusilier Battalions closed in on the left flank of the great mass of French infantry on the ridge. On the other flank of Hoghton’s brigade, Abercombie’s three battalions had likewise worked forward, wheeling inwards so that the dense French column was caught in a cross-fire. Their losses had already been very severe and they could not stand the new ordeal. The great mass, after frantic efforts to charge or to deploy and answer the devastating fire of the British battalions, eventually surged backwards in a retreat which a fierce bayonet charge of all the British survivors converted into a real rout. “In vain,” writes Napier, “did Soult, by voice and gesture, animate his Frenchmen; in vain did the hardiest veterans, extricating themselves from the crowded columns, sacrifice their lives to gain time for the mass to open out. . ; in vain did the mass itself bear up, and, fiercely striving, fire indiscriminatingly upon friends and foes... Nothing could stop that astonishing infantry.

|

The French attack had been repulsed; and the infantry 0f the French Army had been thoroughly beaten; but the Allied Army was equally shattered, and for twenty-four hours the opponents remained facing each other, attempting nothing but the succour of the wounded. Then Soult decided to retreat, and marched back along his tracks, taking with him all those of his wounded who could walk or whom he could carry, save those who still lay on the re-captured hill. The French losses were never exactly stated, but were probably about 8000. The Allied losses were about 6000. Fortescue gives them as 4159 British, 1368 Spanish, and 389 Portugese. All the 13 British battalions engaged lost heavily, but the three devoted battalions of Hoghton’s brigade were almost annihilated. Their losses are shown in the table below. “Such constancy,” writes Sir John Fortescue, “as was displayed by these battalions is rare, and has seldom been matched in the history of war. . . . Whence came the spirit which made that handful of English battalions—for not a single Scots or Irish regiment was present—content to die where they stood rather than give way one inch? Beyond all question it sprang from intense regimental pride and regimental feeling The regimental officers can hardly have failed to perceive that Beresford was making a very ill hand of the battle, but that was no affair of their’s. The great point to each of them was that his battalion was being tried, and that in the presence of other battalions, by an ordeal testing its discipline and efficiency to the utmost. Sergeants and old soldiers. . . took the same view. . . .And hence it was that when one man in every two, or even two in every three, had fallen in Hoghton’s brigade, the survivors were still in line by their Colours, closing in towards the tattered silk which represented the ark of their covenant, the one thing supremely important to them in the world.” “Truly,” adds Sir Charles Oman, “Albuera is the most honourable of all Peninsula blazons on a regimental Colour.” |

Ensigns Edward Furnace and Richard Vance |

Commerative tunic button |

The following are the names of the officers of the 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment who were killed or wounded at Albuera. :— Killed or Mortally Wounded.—Lieut.-Colonel D. White (died 3rd June), Captain J. Humphrey, Wounded.—Major Gregory Way, Captain P. Hodge, Captain G. Tod, Captain E. Nestor, Lieutenant R. Stannus, Lieutenant J. Brooks, Lieutenant T. Popham, Lieut. and Adjut. B. Wild, Lieutenant T. Biggs, |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

French Dragoon |

British Infantry |

British Light Dragoon |

Spanish Artilleryman |

French Hussar |