Nivelle (10th November 1813)

On the very day that San Sebastian fell to the Allies Soult made one last desperate attempt to relieve the place. The attempt ended in failure, however, and the relieving troops were ordered to withdraw. Consequently, 10,000 French troops under Vandermaesen pulled back towards Vera and the fords there across the Bidassoa river which they had crossed that morning. Unfortunately for them, the level of the river had risen dramatically and the only way across the river was via the bridge which spanned the Bidassoa at Vera. However, as they approached it they found their way blocked by Captain Daniel Cadoux of the 95th Rifles. The French were left with little choice but to attack Cadoux and his small party of men whom the French thought would take little brushing aside. In the event, Cadoux held on for two hours, inflicting 231 casualties on the French including Vandermaesen himself, who was killed. Whilst the fighting was in progress Cadoux sent repeated requests to General Skerrett, acting commander of the Light Division and who was aware of the action, but he did nothing, otherwise the whole of the French division might have been forced to surrender.No support was given to Cadoux and finally the 95th were forced to give |

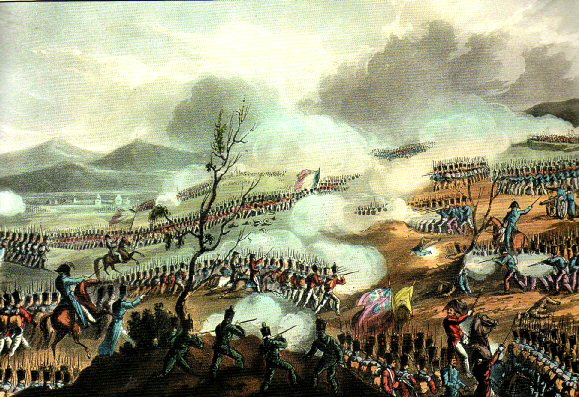

Battle of Nivelle |

way. The brave Cadoux was killed along with sixteen of his men while three other officers and 43 men were wounded. With the withdrawal of the 95th the French were able to gain the safety of the opposite side of the river.

There was no let up in the Allied operations following the fall of San Sebastian. The winter rains were due and Wellington was anxious that his army get as far into France as was possible before the condition of the roads became too bad. At dawn on October 7th Wellington's army crossed the Bidassoa, the first of a series of rivers that had to be negotiated by Wellington's army before he could push on into the heart of France. Waiting to guide the British troops across were some local shrimpers who led the men out across the river which, in spite of its wide estuary, came up only as far as the men's waists at most. The audacious crossing caught the French by surprise all the way along the river and as Wellington's men scrambled on to the opposite bank the French troops made good their escape and only in a few places did they remain to dispute the crossing. By the end of the day the operation to cross the Bidassoa had been a complete success with just 1,200 Allied casualties against 1,700 French.

Once across the Bidassoa and having established his army in France Wellington's next objective was to clear away the French from their positions in front of the River Nivelle. Soult's lines stretched from the shores of the Atlantic on the French right flank to the snow-covered pass of Roncesvalles on the left while the sixteen miles between the pass of Maya and the sea roughly followed the line of the Nivelle, thus giving us the battle's name.

The line was marked by a series of hills upon the summits of which the French had constructed strong redoubts, some containing artillery. These redoubts ran from Finodetta on the extreme left flank of the French position, to Fort Socoa, on the coast opposite St Jean de Luz. Although Soult's overall position grew in strength as he fell back on his base at Bayonne, he did not have enough men to man the lines in depth and was severely over-stretched, the twenty miles of front being defended by just 63,000 men. Wellington's force, on the other hand, numbered 80,000 although 20,000 of these were Spanish troops, many of whom were as yet untried in battle.

Wellington planned to advance along the whole length of Soult's line but would concentrate his attack on the centre in particular. Any breakthrough here, or on the French left flank, would enable his men to swing north and cut off the French right flank. On the Allied left, Sir John Hope would advance with the 1st and 5th Divisions and Freire's Spaniards. Beresford would lead the main Allied attack against the French centre with the 3rd, 4th, 7th and Light Divisions, while on the Allied right Hill would attack with the 2nd and 6th Divisions, supported by Morillo's Spaniards and Hamilton's Portuguese. All preparations for the attack having been made Wellington decided to attack on November 10th.

The French defensive line was dominated by the Greater Rhune, a gorse-covered, craggy mountain some 2,800 feet high. The mountain is fairly accessible to anyone on foot, the rocky spurs only becoming impassable towards the top and on the eastern side. Separated from the Greater Rhune by a ravine, some 700 yards below it, is the Lesser Rhune along the precipitous crest of which the French had constructed three defensive positions. If the French defences on La Rhune could be taken Soult's position would become very precarious as his lines would then be open to Allied attacks from different directions.

The summit of the Greater Rhune was occupied by French troops but, following the crossing of the Bidassoa and the subsequent clearing of the French from their positions along the Bayonet Ridge above Vera, they evacuated it, fearing an outflanking movement that would leave them cut off from their own forces. Before he could consider attacking the redoubts he first had to turn his attention to the French defenders along the crest of the Lesser Rhune. This position was a strong one as the southern face of it could not be assaulted owing to the precipitous slopes that led to the summit. It was possible, however, to attack the three fortified positions by moving down into the ravine before turning to the left which would enable the attacking force to take the French in their flank and sweep them from the crest. Wellington chose the Light Division for the task.

Shortly before dawn on November 10th the division carefully picked its way down from the top of the Greater Rhune and into the ravine in front of the Lesser Rhune. Once this had been done the men were ordered to lie down and wait for the order to attack until suddenly, British guns fired from the top of the nearby Mount Atchubia as the signal for the attack to begin. The men of the 43rd, 52nd and 95th - with the 17th Portuguese Caçadores in support - swept forward up the steep slopes to assault the French positions that ran along the crest to flush the defenders from their rocky redoubts. The men were exhausted by their efforts but the surprise and boldness of their attack won the day and soon those defenders who had not been killed or taken were tumbling down the Rhune towards the redoubts atop the hills below.

While the 43rd and 95th were going about their business, there still remained one very strong star-shaped fort down below on the Mouiz plateau which reached out towards the coast. This was attacked by Colborne's 52nd Light Infantry, supported by riflemen from the 95th. Once again, surprise was the key to their success and as they sprang up from their positions in front of the fort the startled French defenders, in danger of being cut off, quickly fled leaving Colborne in possession of the fort and other trenches. It had been accomplished without hardly a single casualty.

Following this Wellington's main assault began as nine Allied divisions advanced on a front of five miles, French opposition melting away before them, and when the bridge at Amotz fell to the 3rd Division - it was the only lateral communication between the left and right halves of the French army - Soult's position fell with it. This meant that the Soult's army was effectively cut in two. By 2 o'clock in the afternoon the French were defeated and were in full retreat across the Nivelle having lost 4,351 men to Wellington's 2,450. Napier's verdict on the day was as eloquent and dramatic as usual. "The plains of France were to be the prize of battle, and the half-famished soldiers, in their fury, were breaking through the iron barrier erected by Soult as if it were a screen of reeds."

Wellington might have pursued the defeated French even further and there was a very real chance that he might cut off the French right flank. However, darkness was falling and, never one to risk the perils of a night attack, he called a halt to the day's proceeding and his men camped that night upon the ground they had won during the day.