Battle of Talavera (27th-28th July 1809)

Most of the regiments of the British Army have long histories including many famous battles; but many regiments have singled out one battle-honour in particular as a regimental anniversary, and celebrate that battle as their especial Regimental day. In particular, two distinguished Regiments of the Line regard themselves, and are generally regarded by those acquainted with the history of our Army, as being especially associated with two of the most famous battles of the Peninsular War—the classic period of our military history. The Middlesex Regiment cherish the memory of Albuhera, where their 1st Battalion (the old 57th) gained their nickname of "Die-hards"; and they bear “Albuhera” as a solitary legend on their regimental badge. The Northamptonshire Regiment are equally proud of Talavera, where their 1st Battalion (the old 48th) gained great glory; and they display “Talavera” on their cap badge below the Castle of Gibraltar. Our own regimental devices do not “feature” (as film fans would say) any Peninsular battle-honour. And yet it is a fact that the old 29th have every bit as much right as have the 57th to be proud of “Albuhera,” and have an exactly equal claim to the 48th's proud soubriquet, “The Heroes of Talavera”; for at Albuhera the 29th and the 57th stood side by side as units of Hoghton's Brigade in the decisive struggle on “the fatal hill,” and in that fight the 29th fought every bit as gallantly as the 57th, suffering even heavier casualties; while at Talavera the 29th and the 48th stood side by side as units of Stewart's Brigade, rushed forward side by side in the great charge which routed Ruffin's Division, and were equally commended by their grim chief—always grudging of praise (see Note 1)—in his official Despatch.

The desperate battle of Albuhera has always been remembered in Worcestershire Regiment, owing to the heroic episode of Ensigns Vance and Furnace with the Colours; and a detailed account of that battle. But Talavera is less well known in the Worcestershire Regiment, although it equally deserves commemoration.

It should be remembered that the British army had been sent to the Peninsular (i.e. Spain and Portugal) at the request of the Spanish and Portuguese people to assist them in their struggle against the invading French armies of the Emperor Napoleon. Those French armies had beaten the regular Spanish army in battle after battle, and had occupied the greater part of the country, while Napoleon had kidnapped the Spanish Royal Family and had installed his own brother Joseph as King of Spain at Madrid. But the Spanish people refused to accept Joseph Bonaparte as their King, and a fierce guerilla war had broken out all over the country. To suppress the stubborn Spaniards the French armies had been widely dispersed. In the summer of 1809 their forces were disposed as follows: In the central provinces of Spain one French army under Marshal Victor supported Joseph Bonaparte on his dangerous throne at Madrid. Two other forces, under the famous Marshals Soult and Ney, were operating in the north of the Peninsula. In the east of Spain General Suchet was having harassing work around Saragossa, while some distance south of Madrid General Sebastiani was manoeuvring against a Spanish army near Toledo.

That dispersal of the French armies offered a chance of defeating them in detail. The British expeditionary force, under Sir Arthur Wellesley, was in Portugal, its morale and self-confidence restored, after the terrible retreat to Corunna, by a brilliantly successful campaign in the Valley of the Douro. Their leader planned a rapid advance into Spain to effect a junction with a Spanish army which, commanded by a General Cuesta, was operating near the Portuguese frontier, and then a thrust of the combined Allied force against Victor's army at Madrid. If the Spanish capital could be seized, the other French armies might then be beaten one by one.

The bold plan miscarried, because the Spanish generals were hopelessly incompetent and jealous of their British allies. Cuesta's army was only half-trained, while that General himself was bad-tempered, arrogant, and senile, so that co-operation with him was most difficult (see Note 2). Before the Allied armies could bring Marshal Victor to battle his army had been reinforced by that of Sebastiani from the South. The combined French armies advanced, and the outnumbered Allies fell back a little until reaching a favourable position, where they turned to face their pursuers.

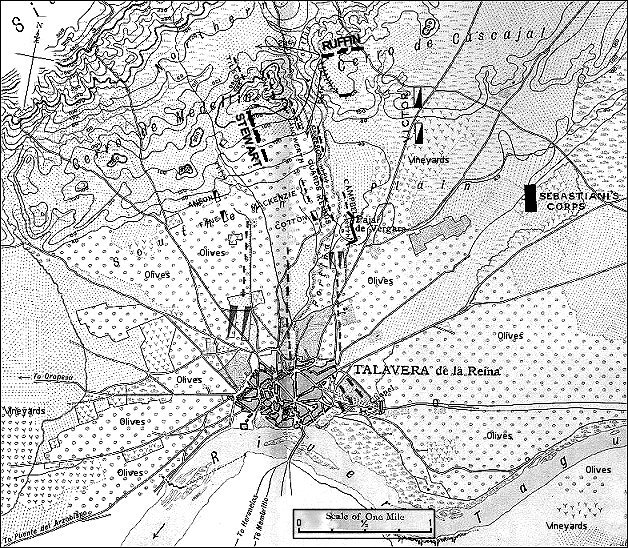

The position taken up was strong, the right flank of the Allies resting on the northern bank of the broad and impassable River Tagus, which at that point flows more or less due west. North of the river the ground slopes up to a chain of rugged mountains, the Sierra de Segurilla, equally impassable. The distance between the river and the mountain chain is about two miles, and there the Allied army took up position on the evening of July 27th, 1809, behind a stream, the Portina, which rushes down from the mountains to join the Tagus at the town of Talavera.

Talavera the night of the 27th July 1809

The Spanish army stood on the right flank by Talavera town. There the low-lying ground was much enclosed, walls and houses affording good positions for defence. The more open ground on the left flank between the Spanish army and the mountains was entrusted to the British army.

The ground on which Wellesley's troops were drawn up slopes gently up for some distance and then rises sharply to a narrow ridge, whose crest is some 250 feet above the level of the river and which runs parallel with the mountain chain. The Portina stream cuts a path clean through that ridge in a deep ravine, as it rushes down from the mountains to join the Tagus in the valley below. The section of the ridge west of that ravine is termed the Cerro de Medellin; the section of the ridge on the opposite bank of the Portina is called the Cerro de Cascajal.

Between that ridge and the main mountain chain is an open plain half-a-mile wide. That plain, dominated by the ridge of which we have told, was left unoccupied by the Allies, whose left flank was designed to hold the Cerro de Medellin. That height was definitely the key of the whole position, since from its crest the ground sloping down to Talavera town and the River Tagus could be completely overlooked; but the height itself was a difficult vantage-point, steep-sided but with only a limited space on its crest. The British commander had intended that this vital point should be held by his finest troops, the Brigade of Guards. But the retreat that day had been confused by an unfortunate rearguard action (see Note 3), the orders had miscarried, and actually that evening the Guards took up position on the lower slope of the hill, leaving the crest of the Cerro de Medellin practically unoccupied, save by a thin screen of outposts.

As darkness fell that evening the British army was still filing into their positions, many regiments missing their way in the failing light. The 1st Battalion Worcestershire Regiment, the old 29th, formed part of Stewart's Brigade in General Rowland Hill's Division. That Division was to be in reserve; and Stewart's Brigade bivouacked at nightfall on the lower slopes of the Cerro de Medellin, well in rear of the front-line position held by the Guards.

Meanwhile the pursuing French, elated by their success that afternoon against the British rearguard, had come on apace, opening fire before darkness fell and causing a considerable panic among the Spanish troops ; a panic which spread to the non-combatants and camp-followers behind the British line. After darkness had closed in the firing ceased, but the march of the French main body was still further hurried. Marshal Victor, making a personal reconaissance in the last hours of that summer's evening, had observed that the crest of the Cerro de Medellin was unoccupied. Realising that this height dominated the Allied position he determined to seize it by surprise after dark.

Accordingly, about 8.0 p.m. a French Division commanded by General Ruffin deployed on the opposite hill, the Cerro de Cascajal, and, covered by the darkness, advanced across the Portina stream to the attack. That Division consisted of three French regiments, each of three battalions—the 24th and the 96th of the Line and the 9th Light Infantry. The latter regiment was to seize the crest of the Cerro de Medellin while the two Line regiments respectively swept the northern and southern slopes of the hill.

That attack struck the British outpost line in the darkness and completely surprised them. After one wild burst of firing the picquets around the Cerro de Medellin were overwhelmed, and the leading battalion of the French 9th Light Infantry rushed up on to the crest of the hill.

The burst of firing from the unfortunate picquets had roused attention; and the British battalions nearby hastily stood to arms. But silence followed, and it was thought to have been a false alarm. General Rowland Hill, commanding the reserve Division, presumed that this was the case, but rode over to the Cerro de Medellin to make sure. He was fired at, as he rode up the slope, by dim figures on the hill; but, assuming “that it was the old Buffs, as usual making some blunder,” he cantered up to them with his staff officer, shouting to the men to cease firing; and found himself in the midst of the enemy. A French soldier caught hold of him, demanding his surrender; but the General spurred his horse, broke loose, and galloped headlong down the hill, amid a storm of firing which wounded his horse and killed his staff-officer. Reaching Stewart's Brigade on the slopes below, he ordered them to attack at once, and led them up the hill.

Stewart's Brigade consisted of three battalions, the 29th (1st Battalion Worcestershire Regiment), the 48th (1st Battalion Northamptonshire Regiment), and a composite battalion made up from details of various other regiments. In the hurry of moving off in the darkness, the composite battalion became the leading unit of the Brigade and came first into action. The details of which it was composed had little unity of command or knowledge of each other, and on meeting the French fire they first checked and then recoiled, firing wildly at the flashes from the height above. But, undeterred by their predecessors' failure, the splendidly disciplined companies of the old 29th pushed through the disordered ranks of the composite battalion and advanced swiftly up the hill until close to the French battalion. Then the leading company of the 29th paused for a moment to deliver one devastating volley, and immediately charged with the bayonet. Before that storm of fire and steel the crowded French ranks gave way, and those of the 9th Light Infantry who had gained the crest of the hill were driven back in disorder down the slope. Apparently the two leading battalions of the French regiment were thus discomfited; but meanwhile the reserve battalion of their regiment was coming up behind them, at a different part of the slope, only to meet a like fate ; for on reaching the summit the whole battalion of the 29th formed line on the leading company, advanced to the forward crest of the hill and encountered the reserve battalion of the 9th Light Infantry still climbing up the steep slope. Struck suddenly by a terrific fire of musketry from the whole deployed line of the 29th, the luckless French battalion recoiled in confusion; an attempt of the French regiment to rally and attack again failed utterly ; and in a short time the disordered enemy retired pell-mell back across the stream. "No praise can be too high for the Twenty-Ninth," writes Sir John Fortescue, "which practically defeated all three battalions of the French 9th single-handed," and this, be it remembered, in darkness, after a sudden surprise, and in spite of the failure of the troops originally in front.

The firing died down as Sir Arthur Wellesley came cantering up the hill to the scene of the fight. Forthwith the British leader ordered a new distribution of the left flank of his line. Stewart's Brigade were to hold the ground they had won, the crest of the Cerro de Medellin, with the victorious 29th on the dangerous outer (left) flank, and the 48th to their right. When a strong line of outposts had been established, and the position was reasonably secure, the troops settled down to rest as best they could, “the furred shako of a French soldier forming in many cases a pillow for the night.”

Sir Arthur Wellesley and his staff shared that rough bivouac, lying on the ground close to the ranks of the 29th. The night was fine and warm but “was one of extreme disquietude and unrest.” Desultory firing came at intervals from the picquets in front, while the rumbling of gun wheels in the distance indicated that the French were deploying for attack; and Wellesley's staff noted that their leader “made constant inquiries as to the hour, betraying his anxiety for the coming of dawn.” His anxiety is understandable when the strength of the opposing forces is taken in to account. The British army under his own command could muster some 22,000 of all ranks, with 30 guns; but many of his units were raw and badly-trained. To his right the Spanish army totalled about 32,000, with 30 guns; but these were mere levies, and the morale of the Spanish army had been shattered by defeat after defeat until whole Brigades would bolt in panic at a mere threat of attack by the dreaded French. The enemy—the combined armies of Victor and Sebastiani—were known to number about 45,000, with 80 guns; all veteran soldiers hardened by 15 years of continuous warfare, during which they had carried their tricolour flag in triumph through nearly every capital city in Europe. The attack of the previous evening had shown that they regarded the Cerro de Medellin as of vital importance, and also that it was the British sector of the line which would probably be struck by the main French attack.

At length the sky to the front grew pale with coming dawn; and the British leaders made their final dispositions. The picquets were called in and replaced by the light companies of the defending battalions, directed to skirmish and delay any attacking force; the other companies of the 29th and 48th were roused and took up position for defence on the Cerro de Medellin, while on the lower ground sloping away down to Talavera the whole Allied army similarly prepared for defence.

As the light grew, the French dispositions could be ascertained. On the low enclosed ground by the river, where the Spaniards were in position, masses of French cavalry were manoeuvring, but there was no sign of any serious attack; while on the crest line of the Cerro de Cascajal, not half-a-mile from the position of the 29th, thirty pieces of artillery were in position, wheel to wheel, and behind them dense masses of infantry. The southern slopes of that hill were alive with battalions moving into position. Actually at least thirty thousand French infantry had been deployed to attack the sixteen thousand foot soldiers of the British force.

There was now no doubt as to where the blow would fall or of its manner. The French tactics in attack at that date bore much resemblance to the method used in the middle of the Great War, during 1916-17, in that they placed no great reliance in musketry fire, trusting instead to the shattering effect of massed artillery, under cover of which their foot soldiers would charge in with the bayonet. To give that bayonet attack sufficient weight, Napoleon's generals were accustomed to mass their battalions into dense columns, which were trained to rush forward in a solid mass, their tremendous shouts striking terror into an enemy already demoralized by bombardment.

That method had proved very effective against Continental adversaries trained in the stiff and formal methods of Frederic the Great. But the British Army had found an effective method of meeting such an attack. As at Crecy and at Mons, the British small-arms fire had been worked up until our men could be sure of delivering a veritable storm of shot. Even with the clumsy muzzle-loading muskets our platoons could fire five volleys a minute; and such a fire could stop any direct attack. To avoid the effect of the French artillery, Wellesley had trained his subordinates to keep their men out of view on the reverse slopes until actually needed; and it was thus that he prepared to meet the French attack. The 29th and 48th were deployed on the reverse slope of the crest, only Wellesley himself, with the Commanding Officers and a few of his personal Staff, remaining on the highest crest line. In front of them the summit of the ridge sloped gently down for some hundred yards to the forward crest, where the light companies were deployed in a line of scattered skirmishers; beyond that forward crest the hillside sloped down much more steeply to the stream below.

The sun rose behind the enemy's position; and at 5 a.m. a single gun was fired from the summit of the Cerro de Cascajal—the signal for the French army to attack. At once the whole line of French batteries opened fire ; and as the smoke of their firing drifted up into the still air the dense masses of their infantry advanced.

Marshal Victor, furious at the previous repulse, had ordered Ruffin's Division to wipe out their failure by now storming the Cerro de Medellin; and General Ruffin had directed against the hill the bulk of his force—the 24th and 96th Regiments, six battalions in all. The French 9th Light Infantry, so roughly handled in the previous attack, were to support the attack by a turning movement on the plain between the ridge and the main mountain chain. The French 96th Regiment was on the left, the 24th Regiment on the right; so that the latter regiment advanced against the ground held by our 29th, while the French 96th confronted the British 48th.

As the French columns advanced, their artillery pounded the hill, their cannon-balls striking and ricochetting all over the hill-top, whizzing dangerously close over the ranks of the 29th as they lay prone behind the crest; but fortunately few of the missiles struck a human target and the actual casualties were few. The light companies extended on the forward slope suffered considerably; and as the dense French columns came surging up the slope the British skirmishers were ordered to fall back. Admirably trained and disciplined, the light companies of the 29th and 48th “filed back” as if on a parade exercise, one “file” firing while the next doubled back to new ground. But it was necessary for the light companies to clear the front before the main line could open fire; and to the nerve-strained commanders on the crest of the Cerro de Medellin the cool retirement of the light companies appeared dangerously slow. “Damn their filing,” shouted General Rowland Hill, “let them come in anyhow “ ; and this was noted afterwards as one of the only two occasions on which “Daddy” Hill, best-tempered and most beloved of commanders, was ever known to swear.

Through the storm of shot the last skirmishers of the light companies doubled up across the gentle slope of the hill top and passed behind the ranks of the battalion. The cannon-balls ceased to howl over the crest as the French gunners shifted their fire to avoid hitting their own men; and with a roar of hoarse cheering, a bristling mass of bayonets and tall shakos, the massed French regiments came surging up over the forward crest of the hill.

Each of the two attacking French regiments consisted, as we have said, of three battalions, averaging at that time about 480 strong. Their battalions consisted of six companies (about 75 each), and were formed for the attack in close column of double companies. The battle formation of a French company was three deep, so that the French battalions were marching in nine ranks with a front of about 50 men.

Apparently the French 24th, who attacked our 29th, came up the slope with two battalions in front line and one close behind in support, so that as the French regiment reached the summit it presented a mass eighteen ranks deep, but with not more than a hundred men in the front line.

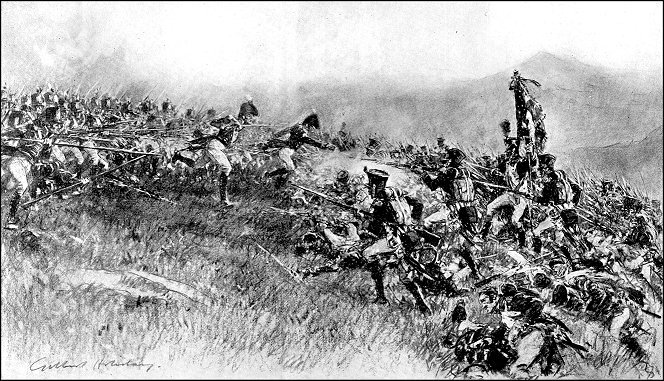

Charge of the 29th (Worcestershire) against the French 24th Regt. on the Cerro de Medellin (28th July 1809)

As that dense mass surged up into sight, the Brigadier, General Stewart, called out “Now 29th ! Now is your time!” Colonel White (see Note 4), commanding the 29th, called the Battalion to their feet and advanced them to crown the crest of the hill. Swiftly the companies dressed their ranks and loaded their muskets. The battalion stood in a long thin line of red coats, two deep, every man ready to fire (see Note 5). In that formation the right half of the Battalion alone was more extended than the whole massed French regiment advancing against them (see Note 6). The left half battalion was wheeled back a little to face the French 9th Light Infantry on the outer flank (although that badly beaten regiment was making no great effort to advance). On the right of the 29th, the 48th faced the French 96th of the Line.

Then the whole British line broke into a blaze of rapid fire; and before that fire the leading ranks of the French collapsed in heaps. Their dead and wounded men checked the onrush of the ranks in rear, who crowded up into a disordered mass. A few of the foremost French soldiers answered the British fire as best they could, but without much effect. Through the dense smoke of the firing it could be seen that the stricken French ranks were wavering; and Sir Arthur Wellesley, standing by the fluttering Colours of the 29th, ordered a charge.

With a tremendous roar of cheering the right half battalion of the 29th and the whole line of the 48th rushed forward down the easy slope, dashed through the drifting smoke-cloud and struck the shattered ranks of the French. Despite the latters' numbers they could make no stand; and as the British bayonets and pikes came thrusting into the reeling mass, the French front ranks gave way. Their rear ranks, on the steeper slope below, were forced back by the weight of the crowd in front, and in a minute the whole six battalions of French infantry were sent hurtling down the precipitous hillside into the ravine below.

The triumphant redcoats chased their defeated enemies down to the stream and even up the slope beyond. Then they were rallied; and so completely had the French been beaten that the British companies were able to re-form at their ease in the ravine before re-climbing the hill to their previous position. Their losses had not been very heavy; but several hundreds of the French were strewn over the face of the hill. Many trophies were secured by the 29th, including two French Colours (see Note 7).

After that success, the battle died down for a while; but was renewed later in the day. The French made no further attack against the Cerro de Medellin, although the hill was subjected to heavy bombardment; but on both sides of the hill the battle raged; and the 29th, from their position on the hill-top, became spectators of as desperate a struggle as any in the Peninsular War. A great mass of French infantry surged forward against the centre of the British line, only to be met and repulsed by the concentrated British fire. The British battalions then counter-attacked with the bayonet and drove the French back across the Portina stream, but were then themselves counter-attacked by French reserves and were driven back in confusion. Even the Guards were thrown into disorder, and the centre of the British line seemed broken; but Wellesley ordered the 48th down from the Cerro de Medellin to assist the Guardsmen, and that splendid battalion restored the fight.

To the northern (left) flank of the Cerro de Medellin an equally spectacular fight took place. During the main attack of Ruffin's Division neither side had extended their outer flanks much beyond the Cerro de Medellin, but now, as the battle swayed in the centre, the French deployed a considerable force of infantry in the plain, half-a-mile wide, between the ridge of the two “Cerro's” and the main mountain chain. To check that outflanking movement, Wellesley likewise extended the British left flank, and sent thither a cavalry brigade of two regiments. One of those two regiments was Hanoverian, the First Hussars of the King's German Legion, and the other British, the 23rd Light Dragoons. Those two regiments were ordered to attack the oncoming French infantry, and the soldiers of the 29th on the Cerro de Medellin cheered them as they cantered forward into action.

The open plain over which the cavalry moved was covered with long grass, which hid effectively a formidable obstacle—a narrow and deep watercourse (virtually a “nullah” ), twelve feet wide and a good eight feet deep, with sheer, crumbling sides, close in front of the French battalions. The two regiments sweeping forward at high speed came suddenly on this obstacle. The Colonel of the German Hussars pulled up short, exclaiming, according to tradition, “I vill not kill my young mensch!” ; but to the hard-riding officers of the 23rd Light Dragoons the nullah was no worse an obstacle than many in the hunting field, and they went at it unchecked. A few cleared it in their stride, many scrambled down into it and up the other side, several came to grief; and the British squadrons were thrown into complete disorder. But without pausing the reckless Light Dragoons galloped onwards and charged the enemy. The French battalions had hastily formed square, and against their bristling bayonets the gallant horseman could effect but little ; however, French cavalry in rear offered a chance of a fair fight; and some parties of the Light Dragoons rode at them so fiercely that the French horsemen swerved away from the encounter. But the horses of the British cavalry were by then exhausted, numbers were hopelessly against them, and the Light Dragoons suffered heavy loss before their scattered survivors returned to the British lines.

Although disastrous to the Light Dragoons themselves, that gallant attack successfully held up the French outflanking movement. The French advance came to a standstill all along the line, and the cannonade was already dying down when, fired by some discharge, the long grass near the Cerro de Medellin suddenly caught fire. Dried by several days of intense heat, the grass blazed up rapidly in a wide belt of smoke and flame, which swept up the slope of the hill, scorching the helpless wounded and burning many of them to death. The 29th and their comrades had hard work to beat down the flames; and when at last the conflagration was subdued the battle had virtually come to an end. The French attack had been definitely repulsed, and the enemy had suffered losses so severe as to make a new onslaught unlikely. Before sunset the French columns were moving back out of range.

That evening for the second time the British troops rested on the ground they had so successfully defended, “Exhausted from want of food, oppressed by heat, tired by the duration of a struggle which seemed interminable,” wrote Colonel Everard. “The fire of cannon” had not yet altogether ceased, and it was not till the close of twilight that the dull rumbling sound of artillery (wheels), heard at intervals and at a distance, seemed to indicate the close of this sanguinary but most interesting battle. A cold damp night succeeded the excessively warm and fatiguing day, and the Regiment, without food or covering of any description, bivouacked on the same spot as on the preceding day."

"At daybreak on the 29th of July, it becoming evident that the main body of the enemy had retreated from view and that there was no necessity for the troops to retain their positions, at 9.0 a.m. the Regiment marched down from the height which, from the commencement to the end of the action, it had had the honour of defending against repeated attacks, and which it now left behind strewn with dead bodies, broken arms, shattered tumbrils, and fragments of shell."

“So ended the battle of Talavera,” writes Sir John Fortescue, “one of the severest ever fought by the British Army.” “Talavera,” said the great Duke afterwards, “was the hardest fought battle of modern times.” And those epithets are justified by the losses. On the French side over 7000 were killed or wounded out of 45,000 engaged, while Wellesley's British Army had suffered 5363 casualties out of their previous strength of 22,000—practically a quarter of the whole force. Fortunately, thanks to luck and good tactics, the casualties of the 29th had not been excessive, considering the desperate nature of their fighting. In all, the Battalion had lost 36 killed, including one sergeant, 147 wounded, including 7 officers, 3 missing; a total of 186 out of a fighting strength before the battle of somewhere about 600 (see Note 8). But the Regiment was justly proud of its great fight and of its captured French colour, and the Regimental spirit, always high, was never finer than in the months that followed (see Note 9). Let us conclude with the description of the 29th soon after the victory of Talavera, written by Captain Moyle Scherer of the 34th (now the 1st Border Regiment):

“On the 7th September, 1809, we marched into cantonments in Spanish Estramadura . . . . Some regiments of Hill's Division lay at Montijo ; amongst others, the 29th . . . . . . . . . . . Nothing could possibly be worse than their clothing; it had become necessary to patch it ; and as red cloth could not be procured, grey, white " and even brown had been used ; yet, under this striking disadvantage, they could not be viewed by a soldier without admiration. The perfect order and cleanliness of their arms and appointments, their steadiness on parade, their erect carriage, and their firm and free matching, exceeded anything of the kind I had ever seen. No corps of any army or nation which I have since had an opportunity of seeing has come nearer to my idea of what a regiment of infantry should be, than the old Twenty-ninth.”

* * * * * * * * * *

List of officers or the 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment

Lieut.-Colonel Daniel White (commanding the Battalion)

Major G. Way

Capatin J. Tucker

Captain S. Gauntlett (Severely wounded on the 28th July 1809, died on the 31st July)

Captain G. Tod

Captain E. Nester

Captain W. Birmingham

Captain T. Gell

Captain A. Patison (In charge of the sick at Plasencia. Made Prisoner on the 31st July 1809)

Captain P. Hodge (In charge of a detachment at Lisbon)

Lieut. A. Newbold (Slightly wounded on the 28th July 1809)

Lieut. J. Humphrey

Lieut. T. Langton

Lieut. St. J. W. Lucas

Lieut. E. S. L. Nicholson (Slightly wounded on the 28th July 1809)

Lieut. R. Stannus (Severely wounded on the 28th July 1809. Left sick at Elvas)

Lieut. W. Duguid

Lieut. A. Gregory

Lieut. C. Leslie (Severely wounded on the 28th July 1809. Left sick at Elvas)

Lieut. T. Popham (Severely wounded on the 27th July 1809. Left sick at Elvas)

Lieut. W. Penrose

Lieut. C. Stanhope (Severely wounded on the 28th July 1809. Left sick at Talavera. Prisoner 7th August 1809)

Lieut. W. Elliot (In charge of sick at Elvas)

Lieut. A. Leith Hay

Lieut. T. L. Coker

Lieut. H. Pennington

Lieut. A. Young (In charge of detachment at Lisbon)

Ensign B. Wild (Left sick at Plasencia)

Ensign John Evans

Ensign Mills Sandys

Ensign George Hillier

Ensign Edward Swinbourne

Adjutant - Lieut. Wm. Wade

Pay Master - T. Stott

Quartermaster - W. Gillespie

Surgeon - G. Guthrie

Assistant Surgeon - E. Curby (In charge of sick at Talavera. Prisoner 7th August 1809)

Assistant Surgeon - L. Evans (In charge of sick at Elvas)

Casualties of the 29th (Worcestershire) Regiment

27th July 1809

Killed - 10 Rank and File

Wounded - 1 Lieutenant (Lieut. T. Popham), 42 Rank and File

Missing - 1 Rank and File

28th July 1809

Killed - 1 Sergeant, 25 Rank and File

wounded - 1 Captain (Capt. S. Guantlett), 5 Lieutenants (Lts. Newbold, Nicholson, Stannus, Leslie, Stanhope), 98 Rank and File

Missing - 2 Rank and File

CLICK HER FOR TWO SUBALTERNS ACCOUNTS OF THE BATTLE OF TALAVERA |

NOTES TO TEXT

Note 1. - The great Duke of Wellington was seldom complimentary; more often he was mordantly sarcastic. On one occasion the 13th Light Dragoons (now Hussars) made a most gallant but unauthorised charge, routing a French cavalry regiment and hunting the French troopers across country for miles, But in so doing they failed to carry out a less spectacular but more important duty assigned to them; and the only acknowledgement their exploit received was a curt note that "if the 13th Light Dragoons misbehave in this manner again, their horses will be taken away from them." Thenceforward the 13th were no favourites with the Duke; and so long as he lived they bore no battle-honours for their Peninsular engagements—in fact, their battle-honours for the Peninsular War were not granted to them until 1890 !

Note 2. - At one critical juncture in the campaign, when success or disaster hung on rapid movement, the proud old gentleman absolutely refused to let his troops move unless Wellesley would ask him to do so on bended knees. The grim British leader fortunately possessed a sense of humour. Asked afterwards how he persuaded Cuesta to move, he said that it became evident that there was no other way of averting disaster, So down I plumped!

Note 3. - In which the French advanced guard had surprised and cut up two young Irish battalions, the 87th and the 88th (Connaught Rangers).

Note 4. - Lieut.-Colonel Daniel White. First commissioned in the Regiment as Ensign, 27.2.1787. Promoted Lieut. 25.8.1790. Captain 1.3.1794, Major 5.6.1799, Brevet Lt.-Colonel 1.1.1805, and succeeded to the command of the 29th (Worcestershire) after the death of Lieut.-Colonel the Honble. George Lake at Roleia. Commanded until mortally wounded in 1811 at the Battle of Albuhera.

Note 5. - The rear rank was trained to fire between the intervals of the front rank men.

Note 6. - In line two deep the right half battalion—five companies of about 50 each—would have had a frontage of about 125, as against the French frontage of about 100 men.

Note 7. - There is much uncertainty as to these French Colours. Each French regiment of three battalions had only one Colour—the tricolour surmounted by a gilt eagle, presented personally by the Emperor. The official Despatch states that “one Standard was captured and another destroyed by the 29th Foot.” If this is so one Battalion must have secured the Colours of both the attacking French regiments—possibly part of the French 96th, after being defeated by our 48th, tried to escape to the right and so became involved in the rout of their 24th Regiment. How the second French Colour came to be " destroyed is not clear—possibly it was torn to pieces in the struggle for its possession. At any rate it is definite that one French Colour remained in the possession of the 29th. It was sent by the Regiment to Sir Arthur Wellesley, who returned it to the Regiment as a fitting trophy of their valour. Afterwards it disappeared, and its whereabouts, if it still survives, are now unknown.

It is recorded that the captured Colour was surmounted by a plate with screw-holes showing that an eagle had surmounted it, but that the Eagle itself was not found. Presumably the Eagle had been unscrewed before the attack and removed for safety. Otherwise our Regiment would now share with the Royal Irish Fusiliers and the Essex Regiment the distinction of bearing an eagle-badge, for having taken a French Eagle in open fight. Two cavalry regiments have the same distinction—the Royal Dragoons and the Scots Greys.

Note 8. - A month previously (15th June 1809) the strength “present and fit for duty” had been returned as :-

1 Lieut.-Colonel

1 Major

6 Captains.

14 Lieutenants

5 Ensigns

6 Staff

36 Sergeants.

15 Drummers

600 Rank and File

(A total of 33 officers and 651 other ranks).

Note 9. - Six weeks after the battle on the 12th September, 1809, Sir Arthur Wellesley wrote ... “I wish very much that some measures could be adopted to get recruits for the 29th Regiment, it is the best Regiment in this Army, has an admirable internal system and excellent Non-Commissioned Officers “