Adventures of Corporal M. B. Hughes M.M.

I served six years, two hundred and eighty-three days in the Army. I joined at Coventry on July 4th, 1938, and was posted to the Worcestershire Regiment at Norton Barracks, Worcester. After thirteen weeks of training and hard graft, I was placed on a Draft and sent first to Egypt, and then straight on to Port Sudan, where we disembarked and I was allotted to “D” Company at a small place known as Gebiet, where we did garrison duty, consisting of marching, training, drinking, shooting, border patrols and all other buckshea jobs the Army could stick across us. On June 10th, 1940, Italy decided to come into the war, so we were moved up to Cassalla on the Eritrean border, where we had our first introduction to action. I am not going to bore you with details of the various battles I took part in, as you will already know as much as I can tell you from the other books already written. Sufficient to say that I played my part in Berentu, Agordat, Keren, Assmarra, Amba Alagi, Mashour and many other skirmishes September, 1941, |

|

found my regiment on the Western Desert. Once more we were doing our little bit for our King and country, plus the war effort. Christmas, 1941, the Regiment, much to our delight, was in Mena, near Cairo, for one wonderful month, and you can bet your boots we made up for all the months we had spent out in the blue. We made the most of that month eating, drinking, sports, and a million other things, but came the fatal day of February 2nd, 1942, we packed our traps.

|

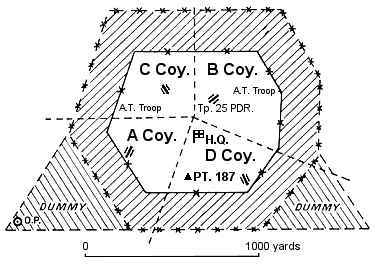

I sewed a L.-Cpl.’s stripe on my sleeve, and we started back up the blue. Patrols, skirmishes, digging, being dive-bombed, sudden moves—all of this was our lot for the next few months. We made and manned the defensive box at Bir-El Cubi, where we had quite our best brush with the enemy. Admitted we had to retreat back into our box, but not before we had inflicted heavy casualties in a much superior force, Next we moved to El Adem, and then off along the Axis road to Acroma. When on the Axis road we were dive-bombed, and “B” Company lost several men and trucks. Acroma ! Maybe you have never heard of that name, but Acroma was part of the Knightsbridge Box that you must surely have heard of at some time or other. Well, we remember it, the men who were there, I can tell you. We have good cause to remember it. Maybe it wasn’t as bad as Dunkirk, but it was bad enough. Our box was box 187. It was one of a line of boxes, and about 7.0 o’ clock, June 14th, the enemy started to shell us. We really got a pasting that night. All night we worked like hell to get our trenches dug, but in the morning we hadn’t got very far down, We were attacked, we threw him back, and so on all day. We had no food or water and very little ammunition. I said my prayers that day, and made my will out too, in my paybook. |

Maybe that sounds kid-stuff to you, or blood and thunder, but, believe me, it didn’t seem like it to me.

It was the toughest spot I’ve ever been in, and I’ve been in some tough ones. Besides, what would you think of your chances of living with your battalion withdrawing, and you, the corporal in charge the forward section, with 150 yards of open ground, all uphill, to cover before you were out of the line of fire, and with the whole of the German 21st Panzer Division and the 8th Machine Gun Battalion giving all they’ve got to you exclusively from 200 yards range?

My section consisted of six men, Posh, Lawrie, Bill, Fred, Keat and myself. Fred was killed straight off by a mortar bomb, having both arms and legs blown off.

I lost three more good men trying to cover that 150 yards of death ground; only Keat and I managed to get through to platoon Headquarters, but we found that everyone else had made good their chance to get out of it while the getting was good.

It seemed to Keat and I that the whole German Army was giving us a real 5th of November send-off, and they threw everything at us from a 88 m/m. to the kitchen sink, but we finally caught up with the battalion. We were never so happy to see the C.O. in all our lives.

We had quite a march to Tobruk, but we reached there in the early hours of the morning, to a lovely cup of hot char with rum.

I think our battalion by this time was about half strength, but we still had to get on with the digging, as we were being dive-bombed all day long. in fact, you could almost touch the planes, but we didn’t bother to do that.

Anyhow, all the damned hard work we put in -on the fortifications in the Tobruk perimeter to stop the enemy was of no use, as he broke through the south aff’s lines on the Saturday night and sent his tanks in to round us up or fix us up according to our reactions. (see Note 2 below)

On the Sunday morning we were ordered to lay down our arms and every man for himself. I didn’t need much urging to get weaving and, if I do say so myself, I didn’t do too badly before a dirty big Jerry captured me; in fact, I got 20 miles. Mind you, I wouldn’t have got that far jf I hadn’t had my pony with me—you know, SHANKS’ PONY, and, do you know, I was in that P.O.W. pen so fast that my feet are still warm.

P.O.W.! That’s when my adventures began, and, if you are still with me, reader, carry on.

I only spent a few days at Tobruk and then I was shopped to Timimi, where we had salt water to drink, 3 ozs. of Iti bully and a biscuit a day. That was our rations until we were moved to Benghazi.

I stopped at Benghazi right up till November 5th, and it’s still 1942.

During my stay at Benghazi I was twice slightly wounded by shrapnel from English bombs, and on November 4th our R.A.F. certainly gave that place the once-over.

Just when I thought I stood a good chance of getting relieved by our boys, the Iti’s moved me to Swanea-Ben-Adem, near Tripoli. This camp was lousy with lice and fleas, and it wasn’t long before I was as lousy as the rest of the boys there. - There was no Red Cross here, so that for almost six months I had to sleep without a blanket and, when one’s wardrobe consists of boots, socks, and one pair of K.D. shorts, one doesn’t like sleeping in the cold sand, does one?

Have I told you about the lice yet? Well, lice were our bosom companions; we were lousy, and I mean lousy. I had more fleas and lice to the square inch than the desert had grains of sand, and I wasn’t the only one, believe me.

Yes, lice are very pleasant bed fellows; they tickled the fancy in more ways than one. After almost five months without a decent wash, you would have thought we had enough discomforts, but not us, as we had very little food given to us and many died of malnutrition; in fact, my mate sold the shirt off his back for 85 dates, and you would have thought we had dysentery after we had eaten them.

Swanea-Ben-Adem doesn’t take much describing; it was lousy, literally and otherwise. There were lousy trees, lousy water, lousy sand; in fact, we were all lousy, and if the reader isn’t itching yet, well, he should be. There’s a difference between lice and fleas. Fleas bite and jump off, but lice bite you and bite again. On November 13th, still 1942, and it was Friday too, we were sent down to Tripoli in cattle wagons, and we were knee deep in the stuff that the cattle had left behind, and some were almost hungry enough to eat it too. After travelling all night, we finally arrived at the harbour of Tripoli, where we embarked on a 2 x 4 tramp steamer, which stunk of everything imaginable, and then some. They piled about 180 of us in a small cargo hold, and many of us had to sleep almost standing. To add to the discomforts, about 150 of us had dysentery. Thank God I wasn’t one of the unlucky ones. November 20th we docked at Trapani, and were placed on a train and sent to Palermo. At this time I was dressed only in a pair of shorts, socks and a topee, and it was raining, but, as you see, I survived. My first real P.O.W. camp was Camp 98, Palermo, and it was here’ we saw our first Red Cross parcel; in fact, we had four between two hundred of us. December 10th we were moved across the straights of Messina to Italy, where we got split up, my party being sent to Camp 68 at Vittrelli, and then we did get a Red Cross parcel all to ourselves, and were we sick! Anyway, I was for one, but who cares about being sick when your belly hasn’t been full for six to seven months. We had just got nicely settled down when orders came through that we were to move off again, so we fell in near the gate on December 10th and marched down to the train, where we were packed into the same old cattle trucks and our journeys once more commenced. |

|

|

We nearly froze to death that night, and, talk about cold, it was enough to freeze the legs off a brass monkey, and then some. Never mind, we all stuck it out and finally the train stopped and we all jumped out to find about 8 inches of snow on the ground. They made us march through this until we reached the camp, which turned out to be Camp 73, Modena. I suppose you would like me to tell you about Camp 73. Well, I’m afraid I can’t, because I spent all day and every day that we were there in my little wooden bed, along with the rest of the boys. So on we go again, and this time we landed at Camp 53, Masscherrata, on February 17th, and the food in this camp was rank. Here are our rations: Bread 200 grams, turnip top stew pint, cheese 20 grams a day, and for the other 23 hours and 49 minutes we went without. Well, we had to do something about this, so we got moved to Camp 102 in L’Aquila. |

By the way, reader, I hope you aren’t getting too fed-up with this little effort of mine, as I should hate to think you had chucked this in the fire, because the best is to come.

L’Aquila is situated about 90 kilos from Rome, and about 20 kilos from the “Grand Sass,” which is the biggest mountain in Italy.

The camp was not too bad, as camps go. We had our Red Cross parcels regularly, and double rations, but, of course, we had to work for it.

I stayed at L’Aquila right up to the date the ITI’s packed in, and what a day that was! We couldn’t believe it, but when we did you couldn’t see us for dust; we didn’t wait for the Germans to come in and send us off to Germany. We just packed enough kit and food to last us until the English troops arrived, which we thought would be no more than ten days, and turned out to be more than ten months for some of us.

So my adventures began. My first night of freedom I spent on the march, and about three o’clock a.m. I arrived in Collibrincioni. (From now on I shall call the above-mentioned place Colli.)

It was at Colli that I met Rosa, an old, fat, dirty Italian woman, with a heart of gold, who told me I could stay at Colli until the English arrived, so I teamed up with Eric, Pete, and Willie.

My mates decided to help the people to get their crops in, and I just took the role of a vagabond (Vagabond in Italian is someone who wouldn’t work, i.e. ME).

I made my headquarters at Colli and, all the time I was on the loose, I always seemed to return there.

There were about 200 P.O.W.’s in the village, and we had a rare old time of it until the first raid. We had been there ten days, and on the morning of the eleventh we were awakened to the sound of shots and the rattle of machine-guns. What a scramble! Everybody running up the hill as fast as they could go. That is, all except Eric and I; we just hid ourselves in the bushes and let the Germans pass over us.

All day long we hid in the bushes and on the night we re-entered the village to find that the Germans had captured 150 of our boys, wounded 2 and killed 1.

We made arrangements for one of the Iti’s to bring us food and went back in the hills, where we met two of our lads who had done as we had, Vivian and John, so we all teamed up together.

We holed ourselves on that mountain near Colli for almost a month, but the old restless feeling came over me, and I made my way to Iragno, another village, where I got my clothes dyed black by a woman called Artimitzio. She was rather a funny woman, with a face of a man, nose like a boxer, broken in about six places, a body like a cart-horse, feet of a navvy and hands as big as a frying pan, but she helped me, so her looks didn’t matter.

She made me into the complete Fascist—black hat, coat, trousers, boots, and even a black belt complete with Benito’s emblem.

I went back to Colli and re-entered the village, and managed to get a real bed for John and myself. Eric and Viv. had moved over the mountains owing to several small raids.

Bit by bit the people of the village lost their fear of Jerry and P.O.W.’s came in practically every day until we had 20 sleeping in the village and about 35 eating off the villagers.

I was by this time getting to be well-known to about ten different villages, in some cases only by reputation.

I was known by my nickname of Sticky, and was Colli’s Pet Prisoner. I was mad, according to the Iti’s, because I took too many chances. I gave the whole village heart failure when I argued with two Germans in the Piattzo over the exorbitant prices they were selling their goods at. I had quite a few narrow escapes from capture in those days. I never worried much; just took everything as it came. I was certain I wouldn’t get killed and I was determined that I'd never go to Germany.

I got rather pally with another John about this time, so we were a party of three. Two of them John’s—John M., the old mate, and John B. the new, and, as it was pig killing time, we were eating rather well.

One morning I left Pasqualina’s, my landlady at this time, and I made my way to Maria Augustina for breakfast, and just as I had seated myself down to pork chops and fried potatoes, in dashed Villina who told me that 200 Germans were on the road below Colli, so once more we P.O.W. s enacted that famous story, “Gone with the’. Wind,’ only we went faster than that. John B. and I made

tracks into the mountains and dug ourselves in and not a moment too soon, as the Germans were almost on us. They machine-gunned all the bushes around us, but not ours. Maybe you think that was a bit of luck; well it was, in a way, because they stood’ on the cliff above us and dropped big rocks into our bushes, and I mean big ones too—not little fifty-pounders either. Anyhow, we weren’t hit, only nearly, not quite. Jerry added a few more that day to his bag, ‘but not me, fortunately.

We crawled back into the village after dark that night, to get our kit. The people begged John and I to hide in the sheep huts and they would fetch us all the food we needed.

Still, John and I decided to move on to better quarters, and started the same night for the front line, leaving John M. in the hills in company with several others, who were all captured two days later by the Germans.

We marched through Kharmada that night and next day arrived at Filletto, where we teamed up with three more P.O.W.’s, who decided to try to pass the front line with us. We left the village next day at about 7.0 a.m.; the Germans raided it half-an-hour afterwards. We had to make our way through San Stephana, which was lousy with Jerry at the time, and John M. and I decided that five men would create too much suspicion, so we went up on our own to Castel Verchio, then to San Benneddetto. We stopped at the latter place for a day to rest, and then moved off towards Bussi, having to swim across the river. We made our way to Tocca, and then to Mannappello, but owing to there being an enormous amount of troop concentration, we retraced our steps and hid out in an old deserted farmhouse near Tocca, where we were joined by two Australians, “Ding dong Bell” and “Mort.”

After a while I got restless again and, as it was nearly Xmas, I decided to make my way back to Collibrincioni to enjoy it.

So once again I resumed my wanderings in enemy territory under the shadow of the Swastika, to be dramatic. This time I went alone, and I decided that I’d take a chance and cross the bridge at Bussi, as I didn’t like water at the best of times, and not at all when there was snow on the ground.

After rather heavy marching I came in view of the bridge and, throwing caution to the winds, I started across, when with story-book suddenness out popped the sentry and demanded’ my papers. I did the best thing I could and showed him my Army 2nd Class Certificate, which I got at Worcester in 1939. I banked all on his not being able to understand it. He was an Austrian, and I’m pretty sure he realised I was not ltalian, but he gave no sign, and told me to get, and get fast. Afternoon found me walking along the main road from Popoli to L’Aquila, hoping that none of the German cars would stop and question me. I rounded a bend in the road and suddenly came across a party of Italian youths under German guard.

The latter immediately took me under their wing and put me among the Iti’s, saying that I was going to work on the railway. No special notice was taken of me, because they took me for an Italian, so, as we were being marched across the bridge at Popoli, I dived over and made my get-away without being spotted. After drying out, I once more started my hiking towards L’Aquila, only this time I kept to the mountain tracks.

I didn’t have much excitement on the way back, and finally arrived one afternoon in Collibrincioni, tired and hungry. I was welcomed back by my friends, who thought I had been killed along with 86 other P.O.W.’s when the train was bombed at L’Aquila station. I only stayed there that day, and went down in the city to live with Angelina’s husband, who was a dustman and street sweeper. He wasn’t a bad chap, and he could talk English a little.

Most of the rubbish he used to collect he put in a dump. He didn’t tell me where his dump was, but I came to the conclusion it was in the kitchen, and if you had seen the state of the kitchen you would have thought the same. Nevertheless, he and Angelina were two of the best, and I don’t know what I’d have done without them.

December the 24th the German Commandant took over the next corridor of flats and I had to move again, so I went back to Collibrincioni, and spent Christmas night at Pasqualina’s house and slept at Roza’s. I wasn’t allowed out at all because the Fascists were very active. I wanted to move off about January 15th, 1944, but they wouldn’t hear of it, and on January 22nd the Fascists raided the village at midnight. They were pounding on the door before I had a chance. I jumped into my clothes and climbed to the top of the house and in amongst the straw. It didn’t do any good; they found me there, and almost succeeded in sticking me with a few inches of bayonet in the process.

Have you ever been beaten with a revolver? If not, it’s a nasty experience. The Americans have a name for it; I think it’s known as being pistol-whipped. Well, I got pistol-whipped that night, I can tell you, but I landed up in the prison camp on my feet, so I had no moan. Don’t get the idea that the Jerries pistol-whipped me. It was the Iti’s and an Austrian.

Ah well, such is life, and once again I was in Camp 102, L’Aquila, which was now under new management, i.e. C.S.M. Parry was now camp leader. I did about eleven days in the camp, getting madder and madder and hungrier and hungrier. P.O.W. life didn’t suit me, and on February 2nd I made my first break from a German P.O.W. Camp. I managed to get a pair of German trousers, one airman’s overcoat, German hat, pair of spectacles without any lenses in them, and I dressed up as a German, using my own boots and English gaiters dipped in cement. I also sewed on two German stripes and became a corporal in the German Army of the Third Reich. I managed to climb into the German guard room, while they were changing guards, and I walked out into the German quarters of the camp.. I saluted one officer, and then headed for the gate. The sentry opened it, and I was outside the wire.

There was a funny feeling in my stomach, and the hair on my neck felt like it was growing at the rate of an inch a minute. Every person in the camp was watching me from the windows. My feet felt like lead, but they tell me I was stepping out like a machine, ‘and as fast. Well, once more I was loose and free to get caught again, so I returned to Collibrincioni for food, and then wandered around the’ hills until I met up with Jim and Ben, two more prisoners of war. I stayed with them ‘until’ March 24th, and on this day I went out on one of my many food patrols, and as it started to snow I delayed my return to ‘the cave until it stopped. In fact, I delayed it that much that I was just in time to meet a Sgt.-Major. Not the typical English type, but the German type. So, my friends, guess what happened. You are quite right: I was back in Camp 102.

That place will haunt me for ever and ever. I always seemed to be going back there.

Well, reader, what do you know about GLASS? That’s a funny question, isn’t it? Here’s what I know about glass, and the glass I mean was an American soldier who was on the opposite’ bed to me. He was one of the finest chaps I met while I was a P.O.W., and he was the life and soul of the camp. I was sitting on my bed, preparing my next escape, and he was the only guy who came up to me and said, "I think I’ll have a go with you.” And here is how we did it. I had some green cloth, and Iti workers in the camp wore green arm-bands, so Louis Glass and I made ourselves some arm-bands the same. I was wearing a pair of overalls like one of the workers, but they had K.G. painted on them, so I had to turn them inside-out, and then put the arm-bands on. We picked up a camp ladder, walked to the gate and asked the sentry to let us out. Louis did most of the talking, because he spoke Italian better than I did. Sufficient to say that 20 minutes later found us well on our way to the hills and a little more liberty.

We made our way, Lou and I, to Collibrincioni, where we went to my old cave, and found Ben and Jim still in possession. We hadn’t been there long before another lad, joined us who had escaped as we had. His name was Tom, and after a good old talk we ‘made our way into the village for supper, returning later to roll up on the cave floor in a blanket each ‘to sleep.

I decided to make my way down to the front again to try my luck, Lou and Tom decided to join me. I took the lead because I knew the way, and once more we started marching to real freedom. Arriving in San Benneddetto, we ran into a bunch of P.O.W. ‘s, who said that they were expecting a guide to the English lines, and said we could go along, which we did. The guide took us along to Cantoni, and handed us over to one of Major Robb’s organisations, who said that we should make the attempt to cross the front line the next night. Everybody expected great things; no one thought of failure. They gave Lou and me new boots, and Tom’ had a new jacket, all of which were signed for. We had a whole Iamb to eat among us, with bread and cheese.

The next night the march began. All night long we marched towards the Mjella mountains. Once we were over them we were in no-man’s’ land and almost safe. We were destined never to make that crossing, because there were three feet of snow on the m3untains on April 7th, 1944. 1 think it was Friday. When light broke, we were at the bottom in a wooded part of the mountains, but it was so cold and we were so near to freezing, that the guides decided to take a chance and try a daylight march.

Well, picture it yourself. Forty-seven men, marching in single file in white snows. We just had to be seen, didn’t we? And we were seen, too, but Jerry was a good chap, and let us get to the top first before he surrounded us with his ski-troops and drove us back into the Compo-di Govo prison. Fancy being P.O.W.’s nearly two years, and just as you saw your own lines you get caught. It was maddening.

As soon as we were sorted out at Compo-di Govo we started our march to Sulmona; my feet felt as though they had been worn down to the hip-bones. When we got there, Lou did a good imitation of a sleep-walker, and all of us slept like logs. They put us into a civvy prison at San Pasquale, and it was as good as America’s Alcatraz Island, I can tell you. We stopped there till April 23rd, a Sunday, and all the time we were planning our escape when the right time came.

They took us outside and showed us our truck. A special one, with steel bars all over, just like a canary cage, only bigger. Once again Lou’s resource came to our aid. He produced a hack-saw out of his belt, and gave it to one of the lads to get cracking, while he talked to the German guard, and I got round the Italian guard with a big knife. All the men we thought we could depend on turned yellow, and I mean yellow. I finished the sawing off, then Lou called me to help him. I placed my knife against the Italian guard’s throat, and warned him that the best way to avoid a personal meeting with 500 saints they always babble about was by being quiet and giving me his rifle. Lou dived at the Jerry, the lamp went out, I swung the rifle and managed to hit Lou in the dark. No one would help us. Men were shouting to the other three guards in the lorry-cabin to stop the truck. I smashed the German to his knees with the rifle, then knocked him to the floor. He fired two shots from a revolver he had pulled out and wounded two men. Then I really crashed him with the rifle. I saw someone in front of me I thought was Lou. He dived through the hole and I followed, and if you think diving through a hole in the side of a truck, in the dark, when it was touching 40 m.p.h. is funny, well, you’re wrong, as it didn’t strike me funny, but it struck damnably hard. I slid along the road first on my back, and then bounced up against a tree, scraping the skin off a perfectly good nose. (I am the only one who thinks it is a good nose; other people have their own views on the aforesaid organ.)

As soon as I struck the tree I took a quick view of my whereabouts, and then I ran like hell for about fifty yards. I dived over or through a barbed-wire fence, and found myself in an Italian’s vineyard.

I met up then with a Scots lad, who said that he had’ dived off just in front of me. I called out a few times for Lou, but I got no answer and daren’t hang around too long, because where I dived off wasn’t far from the P.O.W. camp at ‘L’Aquila. I decided that as Lou and Tom knew that I’d make direct for Collibrincioni and wait for them there, that I’d better get cracking and wait for them. I waited for about three days at Collibrincioni, hoping that Lou or Tom would join me, but they didn’t come, and I found out later that Lou had not managed to escape ‘from the truck, and Tom had split his skull open when he took the jump. Lou is, I believe, at the time of writing, a prisoner of war in Germany, and Tom is with his unit somewhere in England.

After the wait in Colli I decided to join up with the Italian rebels, and I met up then with my third John—a South African. I hadn’t been in the rebels longer than three days when the Germans attacked them and just about slaughtered the lot. Only six of us escaped, two Italians, who happened to be at home at the time, one officer in the German Army, a deserter and a private in the German Army, John and I.

We who were left were rather a mixed collection. We sent the two Iti’s back to their Momma’s, and decided to await the news. When we did get the news, it was enough to get us on the move at once, as the Fascists and Germans were scouring the hills for us, and from what I could make out our names were written on the Black List.

So once more I decided to go for the front, hoping to pass it this time.

Three more P.O.W.’s joined us as we started our march, and here are their nationalities—one Belgian (Umberto), two South Africans (John and Eric), two Germans (Frederic and Carl), and, last of all, yours truly, STICKY, in the flesh.

I was nominated to lead the party to within five miles of the British line, and Carl the German was to lead us through, as this was a sector he had fought on before deserting.

The march was hard, going, but we kept on all that night. The following morning, after a short rest, we started again, leaving Umberto and Eric behind, as they had had enough of it already. That day we were sighted by a party of Fascists, who fired a few shots, but, as the range was too great, they started after us, gathering more Fascists as they followed us through the villages. That march just about finished us all off, and by, the time we were almost in Castel Verchio, Frederic had walked his last 100 yards with us, as he could not walk another step. Frederic was forty-six years old, and was not expected to do what us youngsters could do, I being the next oldest at twenty-three; so we sat him down, nice and comfortable, and then we shook hands with him and left him, hoping the Fascists wouldn’t bother to question him as they passed. Maybe that sounds callous to you, but the Fascists were after four men, not one.

It was the survival of the fittest, and I would have expected just the same treatment if I had been the one who couldn’t make it. He had a fair chance that they wouldn’t bother him, and he had to take it.

We by-passed Castel Verchio, and towards evening we arrived in the vicinity of San Benneddetto, having shaken off the Fascists, through the olive groves or through Fred.

Now I have mentioned San Benneddetto before in this script, and if you remember it was here that I met the guide on the last trip down, so you would expect to find that the people would still feed you. At least I thought they would, but as soon as we stepped into the Piattza we were surrounded by Italians. I recognized many who had fed me before. They had all manner of guns and pistols pointed at us, and the Mayor of the village came out and had us taken into his house to await the coming of the Germans, who had been sent for.

What a time that was, I can tell you! My stomach went as cold as ice whenever I looked at the Italian sub-machine gun pointing at me. Now I look back, it seems rather funny to remember the old chap with that weapon in his hands and the policemen with their pistols—all of them pointing at three insignificant lads without a penknife between them.

We didn’t realize how close we were to being killed by the old man, who didn’t know how to work the sub-machine gun, and was too frightened to take his hands from the trigger until the Germans came and told him how. When the Germans came they were surprised that we were only three in number, as the Italian messengers, true to form, had led them to believe they had captured about 15 desperate men, and they had come up with about twenty men and three trucks. Before they led us away we told the Mayor that we would personally burn his house before the month ended, and as it was May 8th, 1944, we were giving ourselves bags of time to escape, although, as you will see, we were away before we had time to really get questioned. We were taken to Colepiedro, and we refused to talk till we had eaten, and then they started to question us.

First they questioned John, but, as he didn’t know anything about San Benneddetto, they didn’t bother with much more than his name, nationality and where he was first captured; then they turned to Carl, and my heart stood still. I was wishing we could pretend he was dumb or something, as he didn’t know more than two words in English and ten in Italian. German was the only language he knew. We managed to fix it that he was a German-born South African, who was born at Windhook, and only spoke Africanz. This fooled the Germans, and John had to interpret for him, John speaking to him in Afrikanz, and Carl answering in the most unintelligible sounds imaginable.

Now it was my turn and, after the inevitable questions, they asked me what I knew of San Benneddetto; so, knowing that unless the village was fixed, more P.O.W.’s would be caught by the Iti’s, I began to do my best to prove all I could against them. Naming people who I had seen in the Piatzza helping to guard us, telling them where the village store cave was and everything, I must have convinced them, because ‘they burnt half the village down a couple of days later, all except the Mayor’s house, which I had personally seen to myself.

The Germans decided to take us in the village next morning and make us point out the people, so they put us in a concrete outhouse, with two sentries posted outside to guard us. I often wonder what happened to those sentries after, and I would have loved to have seen the officer’s face when he opened the door next morning.

Here is how we managed to escape. There were two bikes in this barn, and I took out the spare parts kit and found two spanners. Then I made ‘Carl watch the sentries through the door, and John and I started to dig under the end wall. It was a forlorn hope and we never expected to get under the foundations, but we found out that this wall was only six inches below ground level, and it followed that the owner of the barn had bricked one end of the barn up and hidden all his worldly goods on the other side. Also there was a small tunnel leading out of the barn to the next door cellar.

We had a hell of a job to get through the hole, as there was a massive trunk up against the wall. Hastily I scribbed a note to the Germans—saying that I was sorry, but we couldn’t stop as we had an appointment, but I’d be quite willing to show them the sights of San Benneddetto another time. John placed this in the hole, and then we picked out a few clothes for ourselves out of the store, after which we crawled out and away once more.

We travelled the rest 0f the night and holed in some bushes all that day owing to the Germans watching for us. That night about midnight we passed once more through San Benneddetto, making sure of the Mayor’s house before we left it. I wonder how the Mayor felt when he woke up to find his feet were scorching. It must have shaken him to realize how promptly the English could keep their promises.

Almost forty-eight hours later, which made seventy-two hours without food, found us staggering out of the mountains to get food. We could not keep going much longer without something to eat. First we met a priest, who gave us bread, and then a woman. Bit by bit we got food, and decided to move on all day asking for food off everyone we saw. We kept going all night too, as we were very near Cantoni, and the English organisation being only about a quarter of a mile from it when we were forced to settle down until day came, as I wanted to be sure I would get the right house.

I spotted the house, but decided’ that it was best to wait till evening, as I didn’t want anyone to know we had arrived there. But the German, Carl, was too cold and we had to risk it, so out we went. We hadn’t gone fifty yards when out of a side lane stepped a German officer, revolver pointed at us. We had no alternative but to go with him. It appears that they had been on the look-out for three dangerous characters such as us, and, would you believe it, we were the right ones.

They questioned us and then sent us into Sulmona, where I had the shock of my life when the same man who had interrogated me before came up again. I don’t know who was the most amazed, him or me. He treated me rather well, and was sorry I hadn’t made it this time. Then he tried to get all the details about the escape from the truck, but, as it would have put me on the spot, I kept my mouth shut. Even the Gestapo had a go at me about the truck, but I still kept mum.

They then sent us to San Pasquali Jail, and I was placed in a cell alone. They told John that I was to be shot; as you can see, I wasn’t.

Some brothel-girl had recognised Carl when we were being marched through the town, and we were questioned for three hours about it, but we stuck to the South African story, and managed to convince them that he wasn’t a German deserter.

Later on I managed to get myself transferred into my old cell, number 25, along with John and Carl, and I blackmailed the Iti guards for everything I could get off them. I said that I might tell the Germans who gave us the saw and the knives to escape from the truck. So we got extra food, cigarettes and other luxuries. Of course, I wouldn’t have told even if they hadn’t, but the only way to get extras off an Iti was to frighten him more than the Germans did.

One night we attempted to get through the wall, using iron which we had broken off the bed, but we got caught at it, so that idea had to be given up.

We decided to try and break away when they moved us, but when they did move us they supplied us with five guards, and we arrived at Camp 102 L’Aquila, safe and sound. Luckily I was not recognised and was allowed to mingle with the other P.O.W.’s. We simply could not manage to escape the same as usual from the camp because my reputation as an escapist was too well-known, and everywhere I went I was followed by other P.O.W. ‘s who were determined to escape with me if I went again. So I was duly marched outside and relieved of my boots and then placed in the truck, which took us up to a place called Terni. I made every effort to slip over the side on that journey, but it couldn’t be done, as the sentry was too careful.

The new camp was a converted factory with wire round it. I studied it from every angle and decided that the only way was to dig our way out by dropping into the lavatory and digging a tunnel, but we did not have enough time to do it, as the order went round that we were to prepare to march out of the camp in three hours time. This didn’t suit me, as I guessed the English armies were getting near, so I decided that when the roll call was made I was going to be missing, and I was. Also Carl, who had decided that I was his best chance of escape, because ‘he stuck to me like a fly to fly-paper. At four o’clock we walked out of the camp and made our way through the fields towards the town.

That same night Carl and I parted owing to the fact that I wanted to try to get through the front line, and Carl was going into the hills.

I slept the night in a bombed house, and the following morning I started to walk through the streets just like any other Iti does, with a great big sack on my shoulder full of old clothes, photos, bread, cheese and other odds and ends. I hadn’t gone far when I was stopped by a Jerry, who put me on a road party to fill in the bomb-holes. I never worked harder in my life. I had to work so that they wouldn’t notice me too much.

Towards the afternoon the English bomber-fighters came ever and bombed and strafed us. Everyone ran for it; I grabbed my coat and sack and also made a run for it. I managed to get out of Terni, and I decided to keep on the main road and head for Reiti.

This was a better plan, as the Germans took no notice of me as I walked down the main road, never dreaming that I was a P.O.W. The roads were full of the retreating army, using every sort of conveyance to carry them. Near Rieti I had a near shave, as I found out too late I was heading for a road barrier. I couldn’t go back, or round it; I had to try and bluff my way through. I had no papers on me at all.

Ten yards from the barrier the miracle of my life happened. Out of the clouds swooped three of our fighters, bent on bombing and strafing the enemy column, and everyone dived to the deck except me. I kept low and ran for the barrier and got past it and well down the road. Later on I was again stopped to fill in bomb-holes, and again our fighters came on their rounds; this time I finished up with a nasty cut over my eye and all the skin off my nose and chin, which proves that a man can’t run with his head one inch from the ground and come out unscathed. I passed through Rieti at midnight and went to sleep in a cornfield until morning, when I was awakened by the sound of movement to find that half the German army had camped on my territory while I had been asleep—at least it looked like that many. I decided to put some bandages on my head and one of my arms to stop the Germans from making me work my passage, and as soon as I was done I crawled out of the field, leaving my bags behind, and started along the road to Rome.

I reached the 78 kilo stone, when the Germans told me that I couldn’t go any farther along the road as civilians weren’t allowed to pass that point, so I headed into the mountains and finally reached a village called Rocco Sinibaldo, where an Italian farmer let me sleep in the manger.

Later on, when he was sure that the Germans had left the village, he took me up to live at his house. I decided that after all I’d gone through I deserved a little promotion, so I became a lieutenant.

There were about twelve other P.O.W.’s in this village and we had a wonderful time. Stacks of food, drink, and lovely beds to sleep in.

I got well in with one of the richest men in the village, who I managed to scrounge about 20,000 lire off. I say scrounged, but he almost begged me to take it, and have a good time with it when I got to Rome; also I was to go and see his sister for him and let her know he was safe.

About the 15th June the first British troops arrived, three armoured cars of them. They gave us fags by the hundreds and offered to take us to their Captain.

I decided not to go that day, but wait’ for a while. After a couple of days I got fed up and decided to start for Rome along with a Yank named Red Phillips. We had a rotten march of it, as it was raining all the time, but we finally met up with a Canadian colonel, named Robertson, I believe, who gave us fags and a lift to the next road block, and once more we started marching. It was on the last forty kilos that Red saw a Fascist, and we both had a few shots at him with our automatics, which we had got from Rocco. We then met up with a Scotch mob, and they gave us a lift to the main Rome road and a good meal too, plus a bar of chocolate.

We hitched a lift with a convoy for Rome and then we reported in to our different barracks. I reported in at 11.0 o’clock, June 21st, 1944, and I was captured at 11.0 o’clock June 21st, 1942, which made two years straight.

Well, that’s just about the end of my little episode. I landed in England on July 7th and was discharged from the Army on February 16th, 1945.

Note 1: This story was originally published in the Worcestershire Regiment magazine "FIRM" in April 1946. Maps have been added by Louis Scully.

Note 2: In fact any of the official histories will show that the breakthrough by Rommel was on the South-East perimeter through the 2/5 Mahrattas, they then defeated the tanks and overran the artillery regts one by one. (Refer map attached from the Durban Light Infantry official history by A C Martin) The South African infantry brigades and the Worcesters were left on the West and South-West perimeter without armour, very little artillery, no transport and no East facing defences and surrender of the fortress was unfortunately inevitable by the next morning. The Worcesters were such recent arrivals that Cpl Hughes probably did not know the details of the defenders positions, although he knew OC Tobruk was the SA Maj Gen Klopper. (Reference Philip Everitt a member - South African Military History Society)