Captain William Leefe Robinson, V.C. - "Zepp Straffers"

The station to which Robinson was "shunted" on 2nd February 1916, was Sutton's Farm at Hornchurch. Part of 19th Reserve Squadron under Major T. C. Higgins, the 'station' was in reality a field.

"There are only two of us night pilots here with two machines kept in tents in a large grass field. We are supposed to go up in case of day or night attack (especially the last as we are supposed to be trained night pilots.) If there are no scares we are only supposed to fly our machines twice a week to see if they are working all right. Today being a lovely day I went up, mucked about a bit, looped the loop four times, and came down. Now don't for heaven's sake get nervous when I tell you I loop the loop—it's the easiest and safest thing to do in the world in the machines we have got." Under Major Higgins, the Home Defence Squadrons were gradually being organised. From the humble beginnings of "two machines kept in tents" 19 Squadron, later 39 Squadron, was to grow to 18 aircraft, in three flights. By July 1916, the squadron, under Major A. H. Morton, was made up of "A" flight under Captain L. S. Ross at Hounslow, "B" flight at Sutton's Farm under Robinson, and "C" flight at Hainault Farm under 2nd Lieutenant A. de B. Brandon. Wooden hangers replaced the tents. The BE2c's were fitted out with more useful night flying aids such as illuminated instrument panels (small lamps fitted above the panels and numbers and hands of dials daubed with "radium") and landing aids (lamps and flares fitted to the leading edge of each lower wing). |

The "Zepp Straffers" of 'B' Flight, 39 Home Defence Squadron |

Experiments with different types of ordnance were made. Many useless weapons were dreamt up by men who had never flown at 12,000 feet, and some were actually put into production. There was yet to be a success against the enemy airships, but the pilots themselves refused to be discouraged.

The months of experimentation were not without cost. Many raids were launched during 1916, with the number of airships increasing steadily. The toll in aircraft destroyed and pilots killed continued to mount. Landing was the most difficult part of the operation. Since the airships were very rarely engaged the planes were landing in the dark with a full set of bombs.

Robinson's flight at Sutton's Farm comprised Lieutenants Brock, Durston, Mallinson, Sowrey and Tempest. The pilots became close friends and for a few months their lives became virtually identical. The hunt for the enemy consumed their energies and thoughts. The rest of the war however could never be forgotten. On 26th February 1916, Robinson's brother-in-law and cousin, Arthur, died of wounds in France. After marrying Grace in 1913 and working for a while in West Africa he had joined the 8th Battalion of the Northamptonshire Regiment. Robinson wrote to his sister, whom he always addressed as 'G',

"My darling girl I wish I had sufficient power of expression to comfort you in the minutest degree. He is a loss—a greater loss than I can express—to all who knew him, but my dear girl one is bound to gain some consolation in knowing that one of the finest men on god's earth has met with the finest ends that man can possibly hope for."

Spring brought a renewal of raids and, at last, some success. In the early hours of 1st April 1916 the combined efforts of the anti-aircraft crews and 2nd Lieutenants Ridley from Joyce Green aerodrome and Brandon from 'C' Flight of 39 Squadron so damaged L15 that it eventually crashed into the sea. The defences around London were gradually improving. In the north of the country however the airships found less opposition, and aircraft continued to crash and explode on take off or landing.

Finally, on 25th April 1916, Robinson had his first chance at the enemy. LZ97, on a solo raid over London under the command of the experienced Hauptmann Erich Linnarz, was soon picked out by searchlights. Of the eight pilots up that night, only Robinson got close.

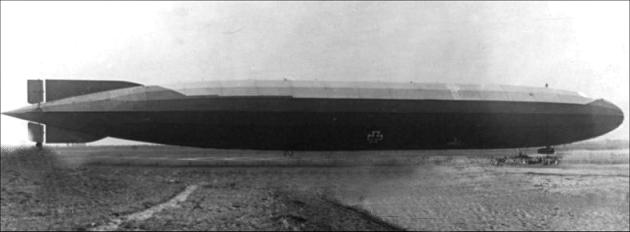

LZ97 Zeppelin

"At about 10.45 a.m. on the night of 25th inst, I received orders to patrol at 5,000 feet. This I did and kept at 5,000 feet for a few minutes, then decided to climb. When just over 7,000 feet, I noticed a great number of searchlights pointing in a northerly direction; turning round I saw the Zeppelin. I at once turned and climbed in its direction. When just over 8,000 feet, I was in a fairly good position to use my machine gun; this I did, firing immediately under the ship. The firing must have had little or no effect, for the Zeppelin must have been a good 2,000 feet above me, if not more (by this time I was about 8,000 feet).

At about 11.20 (by the machine watch which is some minutes fast) I distinctly saw a bright flash in the front part of the forward gondola of the Zeppelin—I thought it rather prolonged for the burst of a shell.

I fired at the Zeppelin three times (each time almost immediately below it): the machine gun jammed five times, and I only got off about twenty rounds. When the Zeppelin made off in a ENE direction, I followed for some minutes, but lost sight of it.

I saw no more of the Zeppelin, and landed at about 1.15. Five sets of flares were visible at my greatest height (11,000 feet) although Hainault Farm was badly laid out, there being far too many lights, and I could make out no distinct The whole countryside, I thought, was very much more lighted up than it had been on previous raid occasions. The river could easily be traced from lights on its banks.

I noticed signalling about five miles NE of Suttons Farm—it appeared to be five fast flashes, then a pause, followed by another five flashes."

April 1916 also brought more bad news. Harold, the brother with whom William had shared so much both in India and at St Bees, was badly wounded in Mesopotamia. He had joined the 101st Grenadiers of the Indian Army, and was attached to the 103rd when the British attempt to relieve Kut-el-Amara resulted in very heavy casualties. Harold died of wounds on 10th April 1916.

During the summer the raids continued. The short summer nights should have helped the defenders but this year the weather was terrible, the mist and fog helping the airships. It was during these months however that the last vital piece in the Home Defences puzzle was fitted into place. Though they did not know it at first the authorities had finally found a type of ammunition that would destroy an airship. The main ingredient was an explosive bullet invented by an Australian engineer John Pommeroy. He had offered his invention to the War Office as early as August 1914 but at that time had been ignored. He tried again in the summer of 1915 and remarkably, was ignored a second time. Only in the early months of 1916 was his bullet looked at seriously by the Munitions Inventions Department. After trials and modifications the bullet, the PSA, was officially approved in August. When used in combination, usually with another exploding bullet invented by Commander Frederick Brock, the Pommeroy bullet proved highly effective. The RFC put in a large order for the Home Defence units. They were the only ones to use the bullet. Supplies had arrived by the beginning of September 1916. They were just in time.